Anne Snyder: Welcome back to The Whole Person Revolution, a podcast of Breaking Ground. I’m delighted to introduce you to Joseph Grenny and Dave Durocher, two men whose lives have been changed by their participation in a stunning community of what you might call reformed rascals. You see, The Other Side Academy is a life training school in Salt Lake City for people with long criminal or addiction histories. Students commit to a minimum of a two-year residence, many as an alternative to incarceration after prison sentences of five or more years, with some having been in and out of jail for 20. It’s entirely self-supporting, peer-to-peer and learn by doing – each day, each minute, really, an invitation to shift who you once thought you were and recalibrate your moral compass – one mistake, one success, one communal ritual and moment of accountability at a time.

Joseph is one of the founders of The Other Side Academy and a bestselling author and leading social scientist in his own right. Dave, well, I’ll let you hear Dave’s story in his own words. But first, let me just say it would be easy to admire The Other Side Academy on outcome grounds alone. Most rehab programs see only about 5 to 10 percent of their folks exit as drug-free, crime-free and employed. But at The Other Side Academy, 70 percent of those who graduate are drug-free, crime-free and employed. That’s impressive.

But what’s perhaps more instructive is that this community, a community made up of viscerally broken people, has not only figured out how to change human behavior (something the best psychologists and social scientists continue to puzzle around in their labs), but they’ve figured out how to cultivate a thick culture normed by integrity, transparency, and mutual accountability, norms that the best leaders in all kinds of sectors crave knowing how to cultivate. And as we all are wrestling right now with heightened questions of authority and trust, power and truth, justice and reform, this community of former felons has something to say. Joseph and Dave, it’s a true pleasure to speak with you both again today.

Joseph Grenny: Likewise. Great to be with you.

Dave Durocher: Yep. Thank you.

Anne Snyder: So, Dave, you direct The Other Side Academy now, and you’ve won a variety of civic awards in Salt Lake City and beyond, but that wasn’t always the case. Could give us a little runway to appreciate where you are now?

Dave Durocher: Yeah. I’ve been very fortunate to have been given the opportunity to come to Salt Lake five years ago and help start The Other Side Academy with a really, really remarkable team. None of this would be possible without Joseph and Tim and the rest of the team. It’s together that we’ve been able to do this.

But prior to that, I was a drug addict for 27 years. Started my use when I was 12 years old, drinking, stealing alcohol from Dad. Of course that didn’t go well once he found out. And then not long after that, I started doing cocaine, and did it all the way through my high school years. There was a lot of chaos during those years as my folks and others tried to help me and point out the error in some of my decision making.

But I was a teenager; I wasn’t listening to anything. And somehow I managed to get through high school, even though I was doing coke the whole way. Here’s a teenager in the 80s doing cocaine, and it’s expensive. To support my habit, I did everything I possibly could. I stole everything that was bolted down and most that wasn’t, figured out a way to manipulate people just to get enough money to support my habit. And that went on for a few years, with a lot of counseling, a lot of therapists, a lot of that kind of help. And none of it worked for me because I thought I didn’t have a problem. “Of course I wasn’t a drug addict.”

Anyway, I graduated from high school, and from there, I went from cocaine to methamphetamine, which is where the wheel really fell off. When I started doing meth, it was a completely different high. For most people they probably don’t know what that’s like, but it got me off of cocaine. The high was longer, it was cheaper, it was a lot better. I never set out to be a drug dealer, but I needed to support my habit. I would just buy some and sell some, buy some more sell some more. One thing led to another and pretty soon I’m buying larger amounts and selling it. And before you know it, here I am dealing drugs. Which then morphed into dealing dealing guns and a whole criminal lifestyle.

As a result of that, I started getting arrested. I did my first prison term. My first prison term was two years. I got out, stayed out for 59 days, got in trouble again, did five years, got out, stayed out for 60 days. So at least I was staying out longer, by one day of course. Went back to prison again for six years, got out for four months, went back to prison for ten. So it was a two-year term, a five-year term, a six-year term, a ten-year term, with very little time out in between those terms. And of course as you could probably imagine, after that fourth prison term, the day I got out of prison, I was on my way back.

And four months later, I got arrested again. But this was a little bit different. I had told myself for many years that if the cops ever tried to arrest me again, if they ever red light me again, I’m not going to stop because I know I’m going back to prison for the rest of my life. I’m in the state of California, so they’ve had enough. They’ve got the three-strike law. I’ve already done four consecutive terms. So when they did red light me and there was a helicopter involved, I took them on a high speed chase. And as you can imagine, that did not end well.

I had complete wanton disregard for public safety. I went through roadblocks and as I got to one of the last intersections, I made the left hand turn and went through that roadblock. I just kind of hunkered down hoping the cops would kill me because I knew that if they caught me, that I was going back to prison forever. But they didn’t shoot. When I made the turn, the cops did the pit maneuver, spun me out of control up on an embankment, and then the car was inoperable and they commenced a rushing up on the car, pulled me out of that vehicle and they beat me senseless.

I remember getting pulled out of the vehicle and when the beating started, the last thing I remember hearing was, “Stop, stop. You’re going to kill him.” We’re in a parking lot of a shopping center, like a strip mall. So there were a lot of people that saw it come to an end, so the officers couldn’t continue to do it without being seen. And when I woke up in jail in the infirmary and I finally went to court about a week or two later, my first sentence was 29 years. That was very humbling. I’d already spent a large portion of my adult life going in and out of prison. Here I sit in jail and I’m on my way back for what looked like the rest of my life.

I fought my case for a long time in the county jail hoping to get it down to something manageable. Now, remember I did a two-year term, five-year term, six-year term, 10-year term. Had they come down to 15, I would have signed the deal and I wouldn’t be sitting here today. Thankfully they didn’t. The judge was very firm and resolute in his decision to say, “Dave, you’re getting this time no matter what.” And that time from 29 had come down to 22 and for well over a year, I fought my case in the county jail. 22 years was the time. Whether I take the deal, whether I go to trial, that’s what I’m looking at.

Rather than just give up, I wrote Delancey Street a letter. Delancey Street is a two-year residential re-education facility widely renowned as the gold standard in the country up until The Other Side Academy started five years ago. There were five facilities, and I wrote the one in Los Angeles. They came and they interviewed me, and they accepted me. But when I went to court and asked the judge if he’d allow me to go, he in no uncertain terms said, “Hell, no, you are not Delancey Street material. You are getting 22 years no matter how long you fight this.”

Of course I got back to my cell, dejected. I was like, “What am I going to do? I’m going back to prison forever.” As I called home, my mom and dad wouldn’t take my calls. My dad had had enough. I’d dragged him all over the state of California, dragged him through the mud just from prison to prison making empty promises that I never kept. They’d had enough. So, not only was I on my way back to prison forever, but I was losing my family.

Every once in a while, though, my mom would answer the phone and I could hear Dad in the background yelling at her to hang up. He was done. And every once in a while, she would come visit me in the county jail against his wishes. I was pitting them against each other with the way that I was living. I didn’t know it then, I didn’t recognize it then for what it was. Later on, obviously, I did. Somehow in spite of my best efforts to destroy that marriage, they’re still married today for 57 years. How is a mystery to me. But that’s another story altogether.

Eventually what I did is I wrote Delancey Street the letter, they accepted me, and the judge said no. And then I wrote the judge a four-page letter, front and back, and I asked him for the opportunity to go to Delancey Street. I said, “Your honor, what do you have to lose? I’ve already been to prison four times. You’re going to send me back for another lengthy prison sentence. Eventually I’m going to get out the same person that went in.” I begged him for the opportunity. I said, “You’ve got nothing to lose. The next time you see me is going to be because I come back to say thank you in your chambers, or you can lock me up if I get kicked out or I split in Delancey Street for the rest of my life.”

Your honor, what do you have to lose? I’ve already been to prison four times. You’re going to send me back for another lengthy prison sentence. Eventually I’m going to get out the same person that went in.

I had no idea what to expect. A month or two later when I went to court in that cage shackled in waist irons and ankle irons, he said, “Mr. Durocher, against my better judgment, I’m going to give you the opportunity of a lifetime. I’m going to send you to the Delancey Street, but you’re going to plead guilty today to all of your charges for 22 years.” I don’t know if you’ve ever felt vertigo where you get bad news or you get good news you’re like, what did I just hear?, and you kind of get that dizzy feeling. That’s how it felt when I got that news that I had been in jail for well over a year of fighting this case, I’m looking at going to prison for the rest of my life, and in a couple of hours I’m getting out to go to a program.

It was really just an odd feeling that’s hard to articulate in words. Not long after that, I was released to go to Delancey Street. And not only did I stay the two years it was required by the courts, I ended up staying eight and a half years. The first two to get out from underneath that 22-year prison sentence, and the next six and a half years because I fell in love with the process. I started to feel good about who I was. I started to realize that I don’t have to live that lifestyle anymore, that there is another way. But around the 18-month mark is when I needed to decide whether or not I was going to stay in Delancey Street longer, or graduate in two years.

I opted to stay one more year. When I asked them to stay they said, “Absolutely, you can stay.” I was a positive role model there. I was doing what was asked. And then at the end of that third year, when I went to that asking again for my commitment, I said I’m willing to stay one more and they said, “Well, why one more, we thought you were in this for the long haul.” I said, “That’s four years by the time I’m done.” They asked me to stay two more and I committed to it. And then not long after that, Mimi Silbert, the president of Delancey Street, came down to LA for a visit and she asked me to stay five more years.

I didn’t know exactly what her intentions were. She just asked me what my plans were and if I’d be willing to stay. I thought about my life prior to Delancey Street, the way I had lived it, and how good I felt in that moment, and I agreed to do that and stayed another five years. So, it was a total of eight and a half years at Delancey Street before I finally left. And when I did, I had a great job in Southern California in the construction trade. I went up to the oil fields and made completely ridiculously stupid money up in the buck for a guy like me who’d been out of the workforce for a couple of decades, and started to put some money away and I started having an affair with my checkbook.

I realized that making money was fun, but saving lives was rewarding, and I moved to the people part. And then by a God shot or just a serendipitous chain of events, I met Joseph Grenny and Tim Stay. Joseph had been having these thoughts for a long time because he wrote the book, The Influencer, featuring Mimi Silbert, and wanted to start something like this in Utah. Joseph and Tim flew to LA, we had our meeting at dinner and we knew right then that it was the right nucleus of people, and not long after that we came to Salt Lake City and found the properties that we currently have and started The Other Side Academy.

I realized that making money was fun, but saving lives was rewarding, and I moved to the people part.

Anne Snyder: Thank you, Dave. Joseph, just picking up where Dave left off, could you tell us a bit about the context within which you met Dave? What was going on in your life and vision at that time such that you two crossed paths and then eventually created The Other Side Academy?

Joseph Grenny: Yeah, it is kind of remarkable that our paths ever crossed. You’ve heard his story. I was on the math team in high school. And so, the likelihood of our paths ever crossing was pretty low from the beginning. And yet here we are, brothers in arms.

As Dave mentioned, my track has been social science. I’d been studying human behavior, why people do what they do and how they change. In 2005, I wrote a book that was based on a worldwide study of really remarkable examples of behavior change. And when it came to criminal recidivism, all the paths led back to Delancey Street. I studied this model. We wrote about the model. I was enamored with it and it just didn’t leave me.

When a couple of our boys got involved in drugs and started in and out of jail, we started seeing how profoundly broken the system is. We started realizing that we’ve created – at a tremendous expense to the public purse – the perfect system for creating criminals. The likelihood of somebody committing second offenses and being reincarcerated goes up dramatically if you have a decent length jail stay. Our department of corrections couldn’t be more inappropriately named. And as I watched my sons getting caught up in this system, and these were people that had a decent support system and options available to them, we saw how many others were caught up in this eddy that they could never escape from. It was about that time that my wife and I said that this is horrible.

We started realizing that we’ve created – at a tremendous expense to the public purse – the perfect system for creating criminals. The likelihood of somebody committing second offenses and being reincarcerated goes up dramatically if you have a decent length jail stay. Our department of corrections couldn’t be more inappropriately named.

When we got to Delancey Street, it’s like we know there’s a cure to cancer sitting in this place, but nobody has found a way to replicate this. This ought to be available everywhere on the planet. And in spite of nudging, it turned out that Delancey Street didn’t have much of an appetite for creating more of these opportunities. And so we thought, all right, well, we got to try. Well, talk about an intimidating thing. I haven’t been to jail. I haven’t been to prison. I don’t know anything about this firsthand. I can talk about it from the outside, but what I know is that any community is no better than the quality of its leadership. And so our first job was to find somebody of tremendous integrity who was deeply experienced in living in and leading this kind of community.

What I know is that any community is no better than the quality of its leadership.

Well, how do you do that? This is a very specialized skillset. Well, we banged our head against the wall for months and finally I had this thought, well, what if somebody on their LinkedIn profile would mention that they had graduated from Delancey Street? So as a hail Mary, we did this search on LinkedIn and did a reverse search for it. It turned out there were 50 people that mentioned this. And that’s what eventually led us to Dave Durocher.

Anne Snyder: How fascinating.

Joseph Grenny: I’ll give you the short version of this story, but it was the most peculiar job interview of my entire life. We met at a restaurant in Los Angeles and as we sat down together I thought, do you do a criminal background check on somebody that you know is a criminal? We talked, and boy, I knew within 15 seconds that this is the man that is capable of creating a wonderful community of integrity that could transform lives. So to me it was serendipity, it was a godsend, it was fate, it was you call it what you want, but this was supposed to happen.

I knew within 15 seconds that this is the man that is capable of creating a wonderful community of integrity that could transform lives.

Anne Snyder: Thank you. The Other Side Academy has now been around for five years. And we could talk forever about the sort of texture of the community as it has evolved as you two, and you in particular Dave, have led it. I’d be happy to hear a quick portrait of it here, but just if you could name and describe some of the key principles that are not just put up on posters actually on the walls of The Other Side Academy’s facilities, and not just a creed spoken aloud, but actually lived every day. These are principles that, yes, are perhaps very powerful in a context of men and women who’ve spent lives jumping maybe from jail to jail and to street and homeless and sort of disordered family backgrounds, et cetera. But when I first discovered them, I found them applicable to any healthy organization and certainly any sort of flourishing community. So what do you think are some of the most powerful principles that make The Other Side Academy the special place that it is?

Dave Durocher: I often say that we are a micro community getting people ready for the macro community. Really what we are here, we get up every day just like everybody else in the community: We put our pants on, we brush our teeth, we go to breakfast, we meet with the family, we go to work, we come home, we take care of our responsibilities. Just like the average person does on the streets, we do that every day. The difference here is the 200% accountability. You got to remember our students on average have been arrested 25 times. So when we get here, there are no exceptions. We are liars and cheaters and thieves and manipulators and self-centered self-seeking people that don’t care about anybody and in most times even ourselves because we don’t know how.

So we immediately on day one start calling you on your behaviors. Unlike what we do in the real world, on day one, it doesn’t matter what it is: If you wink at the girl, if you don’t push your chair in, if you didn’t put the toilet seat down, if you threw the paper across the room, it doesn’t matter what you do, we call you on those behaviors. We address them real time with no lag time. And oftentimes it’s very colorful and vernacular. It’s not like, “Oh Joseph, you shouldn’t do that. You know better than that. Stop that.” We might raise our voices a little bit because you’ve run it three or four times already, and be very colorful and vernacular as we address some of those behaviors.

We are liars and cheaters and thieves and manipulators and self-centered self-seeking people that don’t care about anybody and in most times even ourselves because we don’t know how.

And then of course you have the community that’s going to hold you accountable to those behaviors: good, bad or indifferent. Everybody is held to the same standard – from Joseph Grenny, our founder, Tim Stay, our CEO, to me the executive director or the person who got here today. Everybody is held to the same standard. If Joseph does something, if I do something and they see it, they can call us on our behaviors. And then we have what we refer to as games, which is not games as you would think about it in your head. They’re just groups of people in a room, 20 people deep as we’re addressing each other’s behaviors and everybody is calling each other on their behaviors every day, real time. You can’t get away with anything.

And that really is the magic sauce: the immediate feedback where everybody is accountable, 200% accountable. I’m 100% accountable for me and I’m 100% accountable for Joseph. If he does something wrong and I saw him do it and I don’t say something, then I’m in more trouble than he is because I’m allowing him to do something that’s detrimental to his life or could help kill himself. So across the board, everybody’s held to that same standard. It’s just like when you go to jail or you go to prison, you immediately fit into that culture. You kind of figure out real quick if there’s pressure on the yard, if there’s writing going on, what’s going on, you immediately sense it, you feel it. Here it’s the same way. But we’re very intentional about those things, calling out those behaviors. Very intentional. That’s really an understatement. We’re going to call the students on their behaviors every day that they’re here. That really is our magic sauce.

And that really is the magic sauce: the immediate feedback where everybody is accountable, 200% accountable. I’m 100% accountable for me and I’m 100% accountable for Joseph.

Joseph Grenny: What Dave’s describing that’s important to The Other Side Academy is critical to any social system, any family, any relationship, any company, any community in the world. What we know from 30 years of my research is that the health of any social system is a function of the lag time between when people see concerns and people talk about concerns, period. That’s it. End of story. In a personal relationship, if you have a significant other in your life, the longer it takes for you to be able to discuss those things that matter most, the more mischief happens, the more separation happens, the more games get played.

The health of any social system is a function of the lag time between when people see concerns and people talk about concerns, period. That’s it. End of story.

When you start to broaden that to not just a couple, but a family or even a work team, the problems become endless. All of the politics, all of the silly games that get played in organizations are about lag time. And so the central sickness in our society today is people’s inability to discuss those things, those concerns that they have within these systems. That’s what eventually results in violence, that’s what results in criminal behavior, that’s what results in these ethical scandals that we see. It’s long periods of silence. It’s long periods of collusion and enabling that allows those things to occur.

One of the things that Dave said that I don’t think people would properly understand if they hadn’t been to The Other Side Academy is when he says we call out your behavior. The ‘we’ is anybody in the house. Now, think about what a challenge that is because every organization has to decide which of two values it governs, truth or power. Our default bias, our genetic pre-programming is to be sensitive to power relationships. When we enter a room, we’re trying to look around to say, “Where’s the power in this room?” And we try to defer to that power. One of the ways you differ is by colluding. You support whatever they’re signing up for.

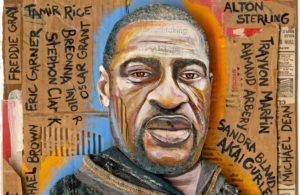

The death of George Floyd was not about a single officer doing something criminal. It was about three people watching it and saying nothing. So even that incident that we’re seeing in front of us today, we’re looking at the pandemic raging out of control, our inability to create norms of something simple like mask wearing is fundamentally about people’s inability to just speak up when they have moral reservations about what somebody else is doing. So where does this come from? It comes to us naturally. And the only way we’re going to be able to create healthy social systems in any areas of our lives is to learn to make conscious choices to create cultures of peer accountability. Not just authoritarian accountability, not just top down, but cultures where truth can speak to power, where anybody who has moral reservations, intellectual reservation, strategic reservations can express those because that’s how we get smart.

Every organization has to decide which of two values it governs, truth or power. …The death of George Floyd was not about a single officer doing something criminal. It was about three people watching it and saying nothing. …The only way we’re going to be able to create healthy social systems in any areas of our lives is to learn to make conscious choices to create cultures of peer accountability. Not just authoritarian accountability, not just top down, but cultures where truth can speak to power, where anybody who has moral reservations, intellectual reservation, strategic reservations can express those because that’s how we get smart.

The Other Side Academy is one of the most remarkable places, but I’ve seen it happen in hospitals, on factory floors, in engineering organizations and customer service centers. And when it happens, everything changes. Employee engagement increases, quality increases, customer retention increases. The Other Side Academy runs world-class businesses. Imagine how would you get a hundred criminals together and run an enterprise that is highly profitable and highly sought after by customers? The only way you can do that is with this culture of peer accountability. This is the central asset that makes any social system work.

Anne Snyder: Thank you for that. When you talk about peer accountability, though, there are different cultural norms in different kinds of sectors and organizations, to say nothing of people from different backgrounds. If you’re in a company which tends to have maybe more of a transactional, less covenantal logic in it, or we’re thinking about something like gender norms, what are the nuances for how peer accountability works itself out?

Joseph Grenny: We emphasize the colorful vernacular with The Other Side Academy just to kind of prepare people for the volume at which it might occur. But that’s not what’s essential about it. What’s essential is that it’s honest and direct. For our community, that’s what honest and direct looks like. If they have to spend too much time trying to calculate the proper verbiage to express something, they’ll get lost and take an off ramp. And so what we say is, just take the shortest distance between how you feel and what you need to say. And that will sort out all the rest later. In an organization, there might be more appropriate ways for you to express it, but directness can’t be compromised.

I spent 30 years writing a book called Crucial Conversations, and I feel bad that it took me 29 years to learn what it really was all about. I thought that it was about packaging and presentation and that if you organize what you wanted to express well enough, then you could reduce the likelihood others will be defensive, which I still think is true. But what I realize now is that a community that wants to be governed by truth and not power, one that wants to create a culture of 200% accountability, it’s more about frequency than it is competency. It’s more about the way to get people comfortable with having crucial conversations is just to have them regularly, not to worry about some specific protocols that everybody has to adopt in order to be able to package the material correctly.

And so at The Other Side Academy, this is what persuaded me. I watch people come in in week one absolutely horrified the same way every executive team I’ve ever worked with is when you start trying to get them to be emotionally honest with each other. These sophisticated executives are just as terrified as these hardcore criminals are when they’re finally asked to be honest about something that concerns them. And the way you overcome that is not just by teaching a bunch of techniques, it’s by just saying, just do it. Just do it over and over and over again. And then what happens is the emotional stakes get lower. Because what those who participate realize is that this isn’t a death sentence. That the fact that Dave is telling me that he really hates what I just did and that I just violated his trust in a significant way, which is conversations that Dave and I have had.

Subscribe

I’ve made significant mistakes in the last few years. But what I realize after we’ve done this ten or fifteen times is that our relationship isn’t over because he’s angry right now. The fact that he’s pulling me up, the fact that he’s correcting me is actually evidence of loyalty and love, not of disapproval and a decision to terminate a relationship. As soon as you’ve gone through that cycle a number of times, your ability to engage in those conversations increases enormously.

Dave Durocher: That’s a beautiful summation of what we do. And I think it’s also important, it’s bizarre to me today that in the “real world,” in corporate America outside of TOSA, we have to be so darn careful what we say and how we say it. We are so careful to not hurt people’s feelings. Let’s digress a minute. Our average student’s been arrested 25 times. They’re out there ripping and roaring and just creating chaos. When they get here, don’t you dare start talking about my feelings. You haven’t cared about anybody else’s feelings in some cases for a couple of decades. Sit down and hear the truth. Truth is love. If somebody would have said something when Harvey Weinstein was marching those little girls up those stairs to his room, how many lives would have been spared? Countless, countless lives would have been spared.

If somebody would have said something when Wells Fargo started opening up all those fictitious accounts, God knows how much money would have been saved. If somebody would have said something when Tom Brady regarding some of that area on those footballs, they might not have won that super bowl.

…When you see something, say something. And what we’re not going to do here is sugarcoat stuff. For years, as people were trying to help me through my addiction and my criminal behavior, oftentimes I’d get a counselor who would sit down. I’d be opining about how I feel or what I was going through. I didn’t feel connected. I could literally see them go, “Oh God.” When David says this, on page 73 of the manual I’m supposed to respond with. Because the connection wasn’t there. They didn’t know what the hell I was going through. How could they, they’d never been through it.

But when I got to Delancey Street and I was around people just like me who had been there and done that, come out the other side, when I would get a haircut, a verbal reprimand for what I was doing, it resonated. It was coming from somebody just like me who had been there and done that already and had already fixed that problem and spotted it immediately. When I got some of those haircuts, I could list a few of them that really impacted my life, I never did that again. Oftentimes here at TOSA, Joseph doesn’t need to get yelled at every time. It’s on an individual basis. It’s based on, what did you do? How egregious was the offense? How long have you been here? What is your pattern? How well do you take feedback?

Can we have just a conversation like this where it’s going to resonate and be impactful and you’re going to make the necessary changes? Or are you fighting it even though we reached our hand in your pocket, pulled the cookies out, you’re still saying they’re not yours. What do you mean they’re not yours? We just took them out of your pocket! We can level a little bit to try to get through to somebody. It’s across the board. Sometimes the conversations are just like this. Sometimes there are 10, it just depends on the situation. But ultimately it’s about the conversation. It’s about taking every single opportunity, no matter what has happened and turn it into a teaching moment.

Anne Snyder: That’s very well said. It’s probably counterintuitive for a lot of folks to hear this, but it’s a very active grace actually working out in every person’s life. And that doesn’t mean it’s all fun and games.

You all have written an essay for Breaking Ground about how maintaining this culture of 200% accountability might illuminate the debate happening very hotly right now in cities across the US around police reform and sort of reform of police behaviors in the wake of all we’ve seen in the last couple of months. First, Dave, I just thought it’s so interesting to ask you to reflect on this. How do you generally view police officers and the whole world of law enforcement?

Dave Durocher: I have a special place in my heart for law enforcement. You would think that the opposite would be true when you hear my history. But I’ve lived on both sides of it. I know what it was like to chase Dave Durocher down. I know what it was like to have the helicopters and multiple agencies after me, getting in high speed chases and fights with the police.

There was a time way back in the early 90s when I pulled up to a hotel. The hotel doors open up, the cops are waiting for me in full riot gear. I’m in a convertible, the top’s coming down. It didn’t quite make it all the way down, and the cops were on me, telling me “give us a reason” as a gun is literally in my mouth.

They pull me out of the car and they handcuff me. I’m on my knees. They’re searching the car and they find two loaded guns. One of them had cop killers in it. They pull the sleeve out. They take the bullets out, and they’re regular bullets with the tops chopped off. There’s a dart coming through the center and they’re Teflon-coated so when one hits a vest, it’s going to go through it. They took that very personally. They stood me up and with one hand swung me in one direction, with the other hand hit me in the face. I’ve never been knocked out in my life, and it rang my bell, and I went to my knees again. They took it very personally.

I was already arrested. They already had me. That never should have happened. Once the high speed chase ended and they had me, the beating never should have happened.

The difference is, I take full responsibility. They did not come to church and pull me out of church for singing too loud in the church choir; they didn’t go to USC in Los Angeles and pull me out for getting straight As. I put myself in those positions to empower them to do what happened. That doesn’t excuse them for how it ended, but I put myself in those positions.

But I love law enforcement and over the past 15 years, particularly the last five, I have tried to foster a relationship with all of law enforcement throughout the Wasatch Valley. From Salt Lake City Police to the UTA Police to the Utah Highway Patrol, we’ve done presentations for them in their precincts to all of their officers. And now, often when the officer runs across somebody on the street that’s a frequent flyer, rather than arrest them and take them to jail, they’ll call me at two o’clock in the morning, put them on the phone or bring them to us so that we can interview them instead of taking them straight to jail. That’s how strong the relationships have become.

I have them come and eat with the students. Sometimes there are twenty or twenty-five officers sitting down having lunch or dinner with the students and I stop them mid meal. And I say, “Stop for a second and look around this room. Law enforcement, when was last time you sat down with this population and broke bread?” And you can see the tears coming down some of the officers’ faces and the students. And I ask the students the same question. When was the last time you sat down and broke bread with law enforcement? The answer from both parties is never, until now.

Law enforcement change is possible. We can change if given the opportunity and the right environment. And students, not all of law enforcement’s bad. Very, very, very few of them are bad. Most of them are remarkably good people. Look what’s going on right now. When you bring two opposing forces like that together, you have to be there to feel what’s going on. I’ve had countless students come to me afterwards and tell me how impactful that was for them.

I just did a presentation to the students the other day and I said, “There’s a big lesson in this. Eventually some of you are going to leave TOSA after two years or three years or four years, and you’re probably going to have some interaction with law enforcement at some point. You may get pulled over, you might be in the wrong place, something’s going to happen. But when you change your paradigm and how you see them, you’re going to respond differently to them, and it could save your life.”

You could have heard a pin drop in the room, and I can’t tell you how many came afterwards and said, “Man, you’re right. I never looked at it like that.” So, it’s changing the paradigm on how law enforcement views us, it’s changing how our students view law enforcement, because ultimately what we need to do right now is bridge the gap between the communities and law enforcement. We want to start that here at TOSA, and it just so happens we’ve been doing it for a few years.

When the riots happened in Salt Lake City four or five weeks ago after the whole George Floyd thing happened, I sat back and I was watching it. It was hard to not cry to watch what was happening in our city. They were burning good cars, they were rioting, they were destroying property, they were being violent. I called the mayor the next morning and said, “Erin, we need to take our streets back. I don’t mean violently or physically, but I want to bring our students downtown with trash bags and canvas the whole area. Let’s clean it up, so that if and when they do come back, they see that they don’t own the streets. We understand that protesting is very important. Some voices need to be heard. There are some things that need to change. Absolutely. But the violence needs to stop too. Cooler heads need to prevail.” She said, “Absolutely.” We brought the entire student body, including Joseph, down there. We picked up trash downtown for blocks until we had canvassed the whole area, and then we came home. It was our way of becoming part of the solution rather than part of the problem.

It’s changing the paradigm on how law enforcement views us, it’s changing how our students view law enforcement, because ultimately what we need to do right now is bridge the gap between the communities and law enforcement.

It just so happens that right next door to us is the Masonic Temple. It has a large parking lot, and two weeks later, that’s where the command center was set up. The Salt Lake City Police department, the UTA Police, Ogden Police, Sandy, West Valley, a number of different police departments were there. The National Guard, bomb squad, FBI, they were all there. Our property is adjacent to it, and the mayor called me on a Saturday night and said, “Would you be willing to go next door with your students and thank the men and women for their service?”

I couldn’t finish my meal quick enough. I came home, brought all the students into the dining room, and explained to the students what we were going to go do. And I said, if you don’t want to do that, for whatever your reasons are, you don’t have to. But here’s what we’re going to do, and if you want to join, let’s roll. 95% of the students went.

The cops were all in their vehicles because it was pouring rain, and word hadn’t gotten to all of the vehicles yet that we were coming. When we walked around our property over to their property, they came out with shields because they didn’t know whether we were friend or foe. By the time they finally calmed down and realized who we were, it was like the air left the room. We came together and spoke to law enforcement for about five minutes about who we are at The Other Side Academy, who we are as the students, who we are in the community, and why we appreciate everybody here. You could see officers and students crying in the rain. It was absolutely miraculous. That’s what we need to do. We need to bring community and law enforcement together. Not just here, but from coast to coast, we need to bring people together and have these conversations.

Anne Snyder: That’s gorgeous. It’s very moving—the paradox and the unity.

Dave Durocher: I’ve gotten a lot of calls from law enforcement that were there that day, thanking us.

Back in March, I was going to have all the chiefs of police here for lunch. This is right when COVID happened. We had lunch ready. And then I got the call that we were to shelter in place, and the meeting got canceled. One police chief out of the entire group ended up showing up. His name was Ken. He walked through the door, and I said, “Chief, sit down.” And we had lunch. We spent probably an hour or an hour and a half together.

He handed me this thing at the end of the meeting, and I was touched. It was hard to not get teared up. It’s a challenge coin that only the chief of police can give somebody. He wrote a small check of $250 to The Other Side Academy because he was so touched at what we were doing.

Then, yesterday, I’m sitting at my desk and I get a piece of mail. It’s a letter from the chief of police from the West Valley Police Department. Inside was a $500 check from him personally, and he said some very nice things. I shared that with the students this morning. No matter what you see on TV and no matter what you’re hearing, not everybody is bad. He did not have to do that. He was touched by what we’re doing, and he cares about you guys individually and collectively enough to write a $500 check to The Other Side Academy to say, “Continue your good work during this critical time.” How wonderful is that?

Anne Snyder: It’s amazing. That story reminds me of last week’s episode where I got to talk to these two wonderful police officers from San Antonio who really helped transform the culture of that particular metropolitan police department through some innovative ways in which they intervene in mental health crises. One theme that threaded throughout that conversation is, we all in our civic spheres inhabit roles, and following the norms of our role is important. However, there’s always an invitation to take off the uniform of your role and live into your common humanity. There’s an element of recognizing we’re actually all broken, and we all have ways to transform, and we all need others to do it. When you can see that happen through what are usually power dynamics between these different roles, it’s a really beautiful thing. I’m moved by what you shared, Dave.

Joseph Grenny: The change in relationship between our students and police is important, but I want to go back to this moment too where George Floyd is on the ground. An officer has a knee on his neck. The whole world is asking, how do we make sure things like this don’t happen again? There’s an important lesson from The Other Side Academy that informs that discussion. There’s so much that people want to look at around structural reform, around changing funding or disbanding entire police departments. Maybe those ought to be pursued, but if you’re going to solve problems, you’re going to have to invest certain people with power, and a police officer has enormous power in those moments.

There’s very little supervision other than peers in those moments. The only real solution is to create a peer culture of accountability. At The Other Side Academy, we have rival gang members sharing dorm rooms, and they’re sitting in games, as Dave described earlier, yelling and screaming at each other at times. Yet in five years of operation, we haven’t had a single instance of violence.

The only real solution is to create a peer culture of accountability.

We spend a lot of time talking about de-escalation strategies but the bottom line is this: If an officer knows when he is handling an issue with a citizen that he’s going to be held accountable by the peers that are standing right there, he won’t make a mistake. He won’t do it. He’ll get up off of that guy’s neck. That will happen. I don’t care how emotionally escalated the situation is. He knows in the back of his mind that there are two people watching him, and that will supersede any other kind of emotional response.

Dave described situations that obviously weren’t racist—just policemen that had the power to do what they wanted in that moment and knew there would probably be no accountability. So whatever other solutions might need to be on the table, starting to create police forces that aren’t about loyalty to a brother but are about truth rather than power must be part of the solution. Or we’re going to have a completely toothless security system that can’t accomplish what the public needs them to.

Dave Durocher: I reached out to the mayor a couple of weeks ago when all this came to a head and asked if she’d be willing to sit down and talk about 200% accountability. I shared with her that nothing’s going to change in the police department until there is peer-to-peer accountability. When an officer takes the dope off the white guy and doesn’t arrest him, but gives it to the Mexican guy and sets him up, or when they pull over the pretty blonde girl and she doesn’t get a ticket, yet they give a ticket to the black guy, or they’re driving and they see a black guy walking down the street and a comment’s made in the car, and nothing gets said between the partners, that’s where the problems are happening. You’re compromising. That’s why the George Floyds happen.

As Joseph said, until there’s peer-to-peer accountability—and I truly believe that if you can have a badge and you can carry a gun and you can risk your life every day, you can sit with your peers and listen to feedback—it’s not going to change.

Anne Snyder: What you’re saying here is actually very rare. You don’t hear this very often, and it’s important, especially in this conversation about police reform and accountability, but not only in that domain. One of the many things that’s so striking about The Other Side Academy is your attentiveness to and understanding of the power of norms, the cultural, invisible things that are part of the fabric of how you actually survive and thrive together. Behavioral norms, moral norms.

Right now, especially among young people, there’s a lot of talk of revolution. “We need to burn everything down, get rid of the way things have been, and just start from the ground up.” Especially in the context of race and our history, but it is inflecting every civic sphere. And yet The Other Side Academy demonstrates that dramatic transformation—revolutionary transformation—happens in these subtle webs of daily choices and the consistency of this peer-to-peer accountability.

In this essay you have written, you write, “Moral decline comes from the thousands of moments when people witness small compromises but say nothing,” which is what you were just describing. You talk about this specifically in reference to law enforcement’s culture of silence. Could you flesh out a little what’s missing in the urgency and heat of this broader national conversation around race and injustice and police reform right now? Is there a maturity or even an awareness of how cultural change happens and how cultural norms get established in a given collective? What’s that dance between dramatic transformation and how that happens in the particulars of the little details?

Joseph Grenny: It’s an unfortunate truth that change is most likely to happen when single instances of egregious problems occur. And the quality of the changes is the lowest when it’s made in those moments, with very little deliberation. We’re talking about some very consequential decisions now in the heat of the moment, and really there are multiple issues here. We have issues in the black community that have been long neglected that are the reasons we have so many people that attract the attention of police, and those must be addressed. And we also have this conspiracy of silence among the police when power we’ve given them gets abused, and that has to be addressed. But these aren’t decisions of the day. I really fear that if we make significant policy decisions, then the pendulum will swing to the other side, and we’re going to pay the price on that end.

Anne Snyder: Dave, do you have anything to add there?

Dave Durocher: Every time I make a decision when my feelings are hurt or I’m mad, I regret it. And when emotions are high right now, as he said, it’s the absolute worst time to make decisions. But it’s the best time to sit down at a table and express how you feel about it. Then, and only then, can you gather all that information, put it in a pool of . . .

Joseph Grenny: Shared meaning.

Dave Durocher: . . . and then discuss then the changes that need to be made. It’s so polarizing, we’re going from one end of the spectrum all the way to the other, and we’re going to pay the price dearly on the other side.

When emotions are high right now, it’s the absolute worst time to make decisions. But it’s the best time to sit down at a table and express how you feel about it.

Anne Snyder: I want to thank both of you. You have a lot to instruct the world at large, and particularly in this moment, with your sobriety, your testimony of human change, and your service outward.

I think there is always hope even in the heat of this current moment in the US. As I was thinking about what makes a community like The Other Side Academy so instructive and inspiring, and the risk you have taken to bet the life of this community on the choices of each individual member and the life of each individual on the collective norms of the community, a C.S. Lewis passage came to mind. It’s about this interdependence between individual agency and communal health:

“It may be possible for each to think too much of his own potential glory, hereafter. It is hardly possible for him to think too often or too deeply about that of his neighbor. The load or weight or burden of my neighbor’s glory should be laid daily on my back, a load so heavy that only humility can carry it, and the backs of the proud will be broken.

It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all only in a nightmare. All day long, we are in some degree helping each other to one or other of these destinations.”

You all embody that constant mutual helping one another to one of those two destinations. I want to thank you for helping me think a little more deeply and intricately about what’s at stake right now, and also about how to leaven the commons with a real practical wisdom. So thank you.

Dave Durocher: Thank you.

Joseph Grenny: We love you, Anne. Thank you for this time.