Anne Snyder: Welcome to The Whole Person Revolution, a podcast of Breaking Ground. Our hope is that in this time of fracture and pandemic, vast uncertainty and societal reckoning, readers and listeners will be given some narrative oxygen by those whose days are spent serving the common good from the crossroads of some of our most sensitive fault lines—whether leading an embattled university, accompanying the disabled and undocumented, discerning the way forward for philanthropy, or sewing the seeds for citywide flourishing across lines of race and politics and class.

Throughout this podcast series, we are going to be hearing from humble heroes whose vocational timbre is lined with an abiding belief in what some of us call the imago Dei, that all people are created in the image of God and as such need to be engaged as integrated human beings, as whole persons. With agility, humility, relational discernment, and a willingness to consider their rights a loss, these community shepherds are subverting the caricatured narratives of our suspicious and polarizing age.

There’s a lot at stake as our society navigates this next year: in and post-COVID-19, and in and after our renewed reckoning with racial injustice. What kind of narrative do these shepherds embody with their very lives, that might instruct the rest of us, that might inform the reform of some our most critical institutions, even as we are each provoked to think more deeply about our relationship to them? How might we support these shepherds, and maybe even join them in stoking the fires of social trust, community resilience, organizational health, and moral renewal?

Today, we’re going to be hearing from two remarkable individuals, Ernie Stevens and Joe Smarro, whom I got to know some years ago after stumbling on rumors of a police department that was changing its moral culture, and doing so from the inside out. Intrigued, I hitchhiked my way to San Antonio, where I became absorbed in a true diamond in the rough of our intersecting debates around criminal justice reform, mental-health policy, social distrust, and police behaviors. Ernie and Joe are cops from that department, very unique ones. And we are reuniting today to reflect on this moment of profound national reckoning around race, the police, trust, and fear. Ernie and Joe, welcome.

Ernie Stevens: Thank you, Anne, it’s good to be here.

Joe Smarro: Appreciate you having us on for sure.

AS: My pleasure. So, this is a pretty amazing time of history and a fraught and precipitous time. Your own field is in the national—if not global—hot seat. So let’s just take it down a peg and hear a bit of your own annunciation moments, vocationally speaking. Why did each of you originally go into the police force?

ES: To be honest with you, it was one of those callings. I knew from a very young age that I was interested in law enforcement. I was drawn to the uniform. I was drawn to the presence that seemed to represent good and authority and right in the world. And I just desired to steer my life path in that direction.

AS: Joe, what about you?

JS: For me, it was not a calling. It was much like when I joined the Marine Corps: It was out of necessity and really having what I perceived as a lack of options. I had had my daughter my senior year of high school, which propelled me into joining the military. And then naturally when you join the military at eighteen, you do your four years, which for me involved a couple of combat deployments from 2000 to 2004. So when I got out as a twenty-two-year-old kid with minimal professional work experience, I had experience of being a traveling combat veteran Marine, but that doesn’t translate real well to much else.

So, whether it was true or not, I felt like I was limited in my options. And so naturally, policing and law enforcement seemed like this pretty easy transition from the military. So I got out of the Marine Corps in 2004 and joined the police department in 2005. And again, for me, it was just like, “I need a job. I don’t have a college degree. I’m not sure what I’m supposed to do in the world.” And so this was just a natural fit, I thought.

AS: That all makes sense. And then time passed and, well, life started happening. Can each of you tell us a little bit about just how this job and the career has evolved for you? What has it become in ways you never could have anticipated in the very beginning?

ES: When I reflect on this question my memory goes back to the Police Academy. I’ve been to two of them, and the first one was twenty-eight years ago. We were taught the most basic foundations of law and not given very much exposure to what was going to be expected of us once we got to the other side. And by “the other side” I mean going out and serving the community. When I joined the San Antonio Police Department, I had to go through their academy, which was about seven months long, same type of experience. They prepared us to know the laws, they prepared us how to handle traffic accidents, just the basic routine-type calls that we’ll respond to in addition to a ton of tactics.

We were taught the most basic foundations of law and not given very much exposure to what was going to be expected of us once we got to the other side. And by “the other side” I mean going out and serving the community.

What they didn’t prepare me for was how to knock on a door and inform somebody that their loved one had just been killed in a traffic accident. What they didn’t prepare me for was the traumatic events that I was going to be exposed to very early on in my field training. So there has been an evolution in law enforcement because now we’re trying to prepare cadets to understand what’s waiting for them on the other side. That they’re going to experience trauma, that there is a great need for them to take care of themselves, to take care of their own mental health. The technology has evolved. I mean, so much has happened so rapidly that it’s difficult for police officers to keep up with all the changes. And that’s why we have our yearly in-service where we get the new mandates that are coming out with policies, procedures, and laws. And it’s a difficult time right now because of everything going on. It’s hard to keep up.

AS: I can only imagine. So, I met the two of you because I’d heard about this very different way of intervening specifically in mental-health crises. Can you describe a little bit for those unfamiliar with your particular kind of policing? Because the kind of work you do is more than a little countercultural according to long-standing conventional wisdom for how police officers should behave and operate on a day-to-day basis.

JS: Yeah, so one of the things that San Antonio is recognized for from a law-enforcement-community perspective is the mental-health unit, which started in December of 2008. It started as a pilot program. Ernie was one of the first officers. And there was another officer who is no longer on the unit. It was six months of “Let’s go test it and see what happens.” And there was obviously a need—they did a good-enough job to where it was very clear that this could grow and be a full-time deal.

Once it actually became a unit, just a short time after, is when I came on. I’ve been doing it almost eleven years this year, and it’s such a counterintuitive way to do what we know as law enforcement, right? I think even in that name, “law enforcement,” which when we’re talking about everything happening right now and changes that need to be made, that’s something in itself that we should look at—the words we use and the nomenclature of certain things. Because we know, looking at things through the lens of mental health, there are debates on everything right now. And while we understand why the problem is the way it is, as far as the mental-health crisis in America . . . we can look back on history and see how deinstitutionalization created this monster that we’re facing right now.

We know that most people don’t think or believe that police officers should be dealing with people who are suffering from mental-health crises. And while at face value I believe that myself—just because you’re someone living with a mental illness doesn’t mean you should have to interact with law enforcement—we also know that there’s a huge lack of community-support services that are able or willing to deal with this situation we’re facing. And so for us as police officers, to get training, to realize that we are the de facto first responders, when it comes to all of these societal issues, whether it’s mental health or homelessness or whatever it is, we have to be better equipped.

So we’re unique in that we wear plain clothes. We don’t look like police officers because we’re driving unmarked cars. We don’t have any identifying insignias on our clothing. Our badges are underneath our shirts and our guns are concealed inside of our pants, under our shirt. So there’s nothing about looking at us on the surface that would make you think that we’re police officers. Yes, that is our primary job, but we show up and our approach is different. It’s, “My name is Joe, I’m with the police department. We’re just here to help you out.” And we really do focus on the person and not the problem. It’s such an important distinction to make. And so that’s one of the things that sets us apart.

We really do focus on the person and not the problem.

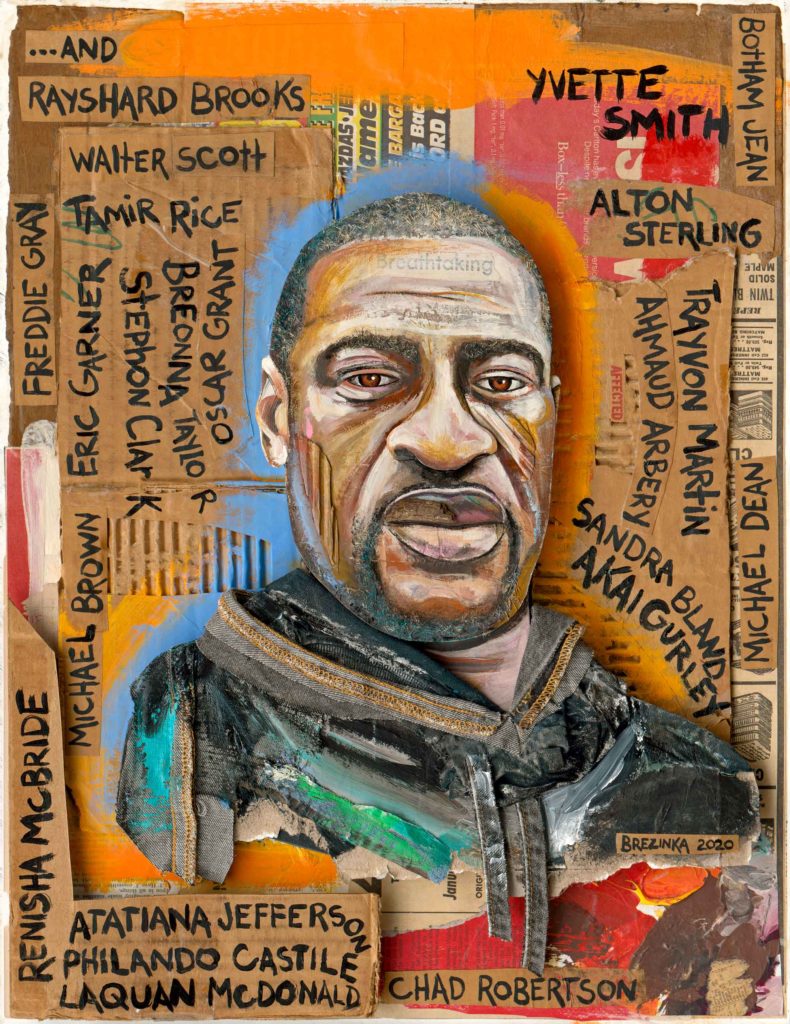

AS: Thank you—we could talk about that all day. But, given where we are today, let’s fast-forward to this really wild, heavy, and loud moment. Many would say, it’s not really a moment, it’s an explosion of long-simmering stuff, particularly vis-à-vis police and racial bias and the whole reckoning that’s happening across the United States. I realize this looks different city to city based on demographics and the cultural ethos of each city, but where you guys are in San Antonio, how would you describe where your minds and hearts have been as you’ve watched all this unfold? The protests, the national conversation, all that’s occurred since George Floyd’s death on May 25 was filmed and shared?

ES: Yes. So I was asked to work in an undercover capacity in the crowd of protestors to just kind of be the eyes and ears of what was going on the ground. We had a large gathering of almost six thousand people show up for a march, which I took part in. After the two-hour march, everybody gathered at a centralized park, and people had an opportunity to speak. And I got caught up in the emotion of it, I’m going to be honest with you. I can feel the pain of what the people were saying. You could see it in their faces. I mean, the tears were coming down. They were asking for police reform; they were asking for justice.

And for a moment, I actually forgot why I was there and that I was even an officer. I was going with what the people were asking for. It was very surreal. And when I left that assignment that night and got home, I sat and thought about everything that was going on around the nation and what the people within our own community felt. They want their voices heard, and they would like a response. It was an incredible experience.

I actually forgot why I was there and that I was even an officer. I was going with what the people were asking for. It was very surreal. And when I left that assignment that night and got home, I sat and thought about everything that was going on around the nation and what the people within our own community felt. They want their voices heard, and they would like a response. It was an incredible experience.

AS: Joe, have you been through something similar?

JS: Yeah, my heart breaks, obviously. I think one of the interesting things was that I’ve never in the history of law enforcement seen such unity so quickly when that video came out of George Floyd being killed. Historically we would hear things like, “Well, let’s wait until we see the other side of the story, or, let’s wait until the video comes out. Or there must’ve been a reason this happened.” And a lot of law-enforcement officers will start to defend just blindly and stand up for their brothers or sisters in blue. And we don’t like the Monday-morning quarterback situations.

But this was one that right away, everybody united. And so while this was a terrible and tragic situation, the hope I have is that we are able to unify around something, though it’s sad that it has to be something like that. But now, like you said, Anne, this was May 25. We’re now in the middle of June on the 18th and people are still going forward with their anger and frustration. And I think that it’s great. We have to use this situation. We have to leverage something to get the attention of people in decisions of making policy adjustments, change, reform, whatever it is. I mean, we’ve had a lot of conversations around things like this. But really, I don’t know that we can point to something and say, “Oh, that’s a categorical, this right here is a huge shift.” Because things have just always kind of been the same way. And it’s amazing that just now in the middle of 2020, you’re starting to see certain police departments come forward and say, “Okay, now effective immediately, we’re banning the chokehold.” How that wasn’t done decades ago. It’s just, it’s so . . . I don’t know, I’m sad, but I’m also hopeful. I think that we have to be willing to listen to both sides. I think we can’t solve the problem at the surface. And so we have to be willing to meet somewhere in the middle and bring people together. Because just staying angry isn’t going to fix anything. We have to be willing to listen, and we have to be willing to solve this collectively.

We have to be willing to listen to both sides. I think we can’t solve the problem at the surface. And so we have to be willing to meet somewhere in the middle and bring people together. Because just staying angry isn’t going to fix anything. We have to be willing to listen, and we have to be willing to solve this collectively.

AS: On that point of listening, and the power of these particular protests to serve as a real tipping point, how would you characterize the listening feedback mechanisms, not only within police departments, but also with the community you’re sworn to protect? Have you experienced a kind of mutual listening there, whether at the town hall or in some other form between a given community and local police? Where you’re able to hear the pain being brought to speech but also share your day-to-day experience, and the goods you have to protect? Is there an opening right now for true listening to occur in a mutual way?

ES: I definitely think there is opportunity here. Here in San Antonio we’ve already scheduled three different community events we’re going to do. Two of them are online with city council and the community. And another one is in person with members of the city council and the community. So, there’s opportunity here. Now, what does that look like? We’re not sure yet. Because we’re still trying to define what this change is going to be and how we’re going to implement it. So, I think we have a lot to learn in listening to the community. Because on the flip side of this, the community may not know exactly what we teach. There are some initiatives out there that call for different types of use-of-force continuums. And it’s very important that we inform our community through education on what exactly we do as a department here. And that it may not be what other departments are doing in other places.

We have a lot to learn in listening to the community.

So when the media highlights something like what happened in Minneapolis, we don’t do that here in San Antonio. We don’t put our knee on somebody’s neck. We would get in trouble for that. It’s not something that we’re trained to do. So I think it’s important that we inform and educate the community. And by holding these town meetings and getting feedback, especially when you’re hearing terms like “defund the police,” you hear that on the surface and everybody gets scared and wants to push back. But what does that mean? How do we define that? How does that affect us? How is that going to affect the community? I think [defunding the police] is not a bad thing if we’re talking about reallocating funds for certain initiatives and community services. It’s very possible, and it can be done. We just need to listen and be willing to make that change.

AS: Yeah. Joe, do you have anything to add there?

JS: Yeah, I think it’s hard right now. I don’t know what the timetable is, but what I do believe is that right now people are still in a bit of a defensive stance, in this defensive mode. And here’s what we know. And I’ve heard this from a friend of mine who is black, and he’s saying, “Look, this isn’t your conversation to have.” And so for us as white people, as white cops, we have to take a back seat. We have to get out of the car even and just allow things to happen organically, and then find out where we’re invited in. Because it’s like, how is it going to actually help move the needle forward if we are the ones saying, “Hey, here’s what we should do, or “This is what you should do”? I think that that’s what’s happened historically, and how has that worked out?

Joe Smarro. Photo by Matthew Busch, 2015.

For us as white people, as white cops, we have to take a back seat. We have to get out of the car even and just allow things to happen organically, and then find out where we’re invited in.

And so I think that we need to have more people of color in leadership positions. We need to have more people of color leading the conversations. This is why I really appreciate what Emmanuel Acho is doing with his new series, Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man. And he has on these white guests, and they have dialogue. And it’s so profound, because I’ve learned so much through watching them. And so I’ve been saying, I saw it. It’s not mine by any means, but I believe it. And it was, “Healing starts when listening begins.” The problem that I’ve seen so with many people is, as soon as they hear something that they don’t necessarily agree with, they get defensive. They start deflecting away from it because they’re uncomfortable. Or they will just completely defend the sentiment that’s being expressed.

And I think that that’s part of what the problem is. We don’t have to necessarily take it personally. But we absolutely have to acknowledge the fact that people are in pain and they have every right to be in pain. There are injustices, and there are inequalities, and it is a serious problem. So we have to be willing to listen and take a backseat role, not try and lead on this front and tell people what they should do or how they should feel. Because I think that’s where we everything just shuts down.

We don’t have to necessarily take it personally. But we absolutely have to acknowledge the fact that people are in pain and they have every right to be in pain.

AS: Yeah, that’s so good. Thank you.

So, for everyone listening, there’s a really incredible, award-winning documentary that came out last year, called Ernie and Joe: Crisis Cops featuring Ernie and Joe and the broader ecosystem in which they operate. What you see up close in the film is this deep listening and treating people first as people before they’re treated as problems.

And watching you two do that day in and day out, while also watching you train other officers, watching the faces of new cadets as they absorb your very different style, what are some of the skills and virtues you may have picked up over the years of this work intervening in mental health crises, that you think might offer something in this moment, one rightly focused on racial discrimination? Is a transfer of wisdom possible?

ES: Yeah, well, when we teach the crisis-intervention training, we’ve heard all the ridicule. “Oh, here comes that ‘hug a thug’ training. These guys, their tactics are poor. They sit down with people.” We’ve heard it all. But what we’ve realized is that in the twelve years we’ve been in the mental-health unit dealing with people who are in the most psychotic state of mind, Joe and I have only had to use force one time. And it was really just kind of a wrestling match. The guy told us, “Hey, you’re going to have to fight me.” So we’ve had thousands of contacts with the community, and none have used force. And the reason is because we are trying to connect with the individuals where they’re at, at that moment. Like Joe said, “Focus on the person, not the problem.” “Focus on connection, not correction.” Which I think speaks volumes in terms of what we’re trying to get across.

We’ve had thousands of contacts with the community, and none have used force. And the reason is because we are trying to connect with the individuals where they’re at, at that moment. Like Joe said, “Focus on the person, not the problem.” “Focus on connection, not correction.”

I understand that officers live in a hypervigilant state of mind. That was me for a lot of years, to be honest with you. But when you listen to family members come in and speak to the class that we’re teaching, and they describe what it’s like to grow up with a family member that has mental-health issues, you realize very quickly, “Look, this person that’s in this crisis didn’t choose to want to live like this.” So what we need to do is show up and be vulnerable ourselves, be transparent, be authentic. And really offer a helping hand in a way that shows humanity to our neighbor, right? Our community. And that’s what we’re trying to get across.

Ernie Stevens. Photo by Matthew Busch, 2015.

It’s not a hug-a-thug process. It’s not about being a softer, gentler police department, right? It’s about doing things smarter and doing it in a way that offers the best possible response to the community that can offer treatment and recovery. And that’s what we’re trying to bring to every class that we teach.

So what we need to do is show up and be vulnerable ourselves, be transparent, be authentic. And really offer a helping hand in a way that shows humanity to our neighbor, right? Our community.

It’s not a hug-a-thug process. It’s not about being a softer, gentler police department, right? It’s about doing things smarter and doing it in a way that offers the best possible response to the community that can offer treatment and recovery.

AS: Let’s talk about power. It’s a huge word (and issue) right now, and I think a lot of people are opening their eyes up to its invisible and not-so-invisible presence in all kinds of rooms. But it’s also being weaponized in our broader identity politics. Is there such a thing as a wise use of power? How would you reflect on power in your own experience as cops, particularly doing crisis intervention training? Has your understanding of power changed in part because of the relational way in which you engage your role?

JS: I love that question, Anne, because with great power comes great responsibility, right? And so I teach the officers this entire concept on this paradoxical shift, on power and authority. It’s such an important piece that a lot of agencies—I would venture to say most agencies—probably are not getting and do not understand. Because if you look at law enforcement as a profession, we have been fully weaponized. Look at the whole militarization of policing in this country. And you see it, you know? There are a lot of issues, I believe, in which we really are doing a disservice to our profession from the beginning—the way we recruit, the way we hire. Look at any recruiting video, it’s usually high-speed, heavy-metal music and shows the minutiae of police work that most officers will never do. I think that we’re sending the wrong message.

And a real quick caveat, and I’ll get back to this, but I think it’s important. I was talking to a friend the other day, and I was telling him, “I’m really concerned about what’s happening right now from a national scale that this is in essence a recruiting tool for law enforcement, but for the wrong people. We don’t need people to come into this job and say, ‘You know what, I’m tired of seeing this. I’m tired of looking at what’s going on.’ And they want to be a martyr and show up to this job, thinking that they’re going to help us.”

I’m really concerned about what’s happening right now from a national scale that this is in essence a recruiting tool for law enforcement, but for the wrong people. We don’t need people to come into this job and say, ‘You know what, I’m tired of seeing this. I’m tired of looking at what’s going on.’

I’m afraid that we’re recruiting the wrong people. And I think that we’ve been missing this opportunity for quite a while. But specific to this whole power term, I’ve been long telling officers, what allows us to do a good job is being out of uniform and having the ability to effectively de-escalate as soon as we show up. Because uniform presence is the first step on this force continuum, which again needs to be looked at and really thought over. But just showing up in uniform . . . what are they seeing? They see a badge, which represents authority, and they see a gun, which represents that things could absolutely go terribly wrong if I don’t do X, Y, and Z. And for some people, those rules are unknown.

And so I tell officers, “You have to be willing to understand that the more power and authority you flex or force onto people, the harder you’re going to have to work to gain it. The less power and authority you demonstrate, the easier it’s going to be to gain compliance.” And so for me, that’s why, when people look at us from the outside in, especially law enforcement, and they think the problem is that we’re using using poor tactics and all this, my argument is: I’ve been in an actual combat. I’ve been in war in Iraq. I’ve been in an actual firefight. I am very familiar with tactics. I’ve been trained really well.

I have never seen a war in America that constitutes the need for the type of warfare training that I received in the military. And so, while we have to be safe, and we have to have certain sound tactics, I also know that the more we show up and force ourselves onto people, the harder we’re going to have to work to gain compliance. So yeah, I purposefully will kind of slouch around. I’ll sit down if I can, because I want to demonstrate subconsciously to them that, “Hey, I’m not a threat. I am equal or less than you. I’m simply here to help you out.” And that’s why it’s worked out for us.

I tell officers, “You have to be willing to understand that the more power and authority you flex or force onto people, the harder you’re going to have to work to gain it. The less power and authority you demonstrate, the easier it’s going to be to gain compliance.”

But when you see this officer showing up with outer-carry tactical vests and nine magazines and smoke grenades and zip ties, it’s like, out of your mouth you’re saying, “I’m here to help you out,” but the human brain cannot make that distinction. It’s like, “Wait a minute. This military officer is at my place, or my house or my work scaring the hell out of me physically, but you’re telling me you want to help me? I can’t really wrap my head around that.” And so they’ve got barriers up right away, and we’re just not paying enough attention to that and why that’s part of the problem.

AS: That’s really well said. Thanks, Joe.

You talked about compliance, and I hear you. And I think I can imagine in any given intervention or in any given call, compliance is all you could hope for. But talk a little bit about that. When we’re thinking about broader, long-term cultural shift in trust between communities and law enforcement, trust feels like a much higher bar than the immediacy of compliance, and obviously, much harder to build. But you all have built trust with individuals whom you originally just needed to comply with your desire to help them. Again, yours is the mental-health context. But I’m just curious if you could talk a bit about the delta between that moment of needing compliance and working for the sort of the subtlety and subversion of power you were describing, Joe, to a much deeper gain for everyone, which is trust. Which is probably one of the hugest things lacking across the board in our society these days.

Have you seen the general public trust in San Antonio get further and further eroded vis-à-vis law enforcement over the years? Or is it a much more complicated story? And not just trust between citizens and cops, but also the trust you all have had to build with other institutions in town to complete the circle of necessary supports for all those you encounter in need of comprehensive mental-health treatments?

ES: Yeah. I think trust is the number-one issue that every police department has to have within their community. And so when we talk about that, there are two types of authority: there’s legitimate authority, which the community gives you as a form of trust. And when you lose that, then officers, as you’re seeing across the nation, are going to have to rely on statutory authority. And I think at that point you start to lose trust. But in the middle of those two authorities is procedural justice. What process is taking place that ensures the individual you’re dealing with feels that they can trust you? Are you being legitimate? Are you being equitable? And right now the trend is just horrible based on what we’re seeing on television. Officers have lost legitimate authority, as you can see with some of the looting and the rioting that’s going on in some cities.

Trust is the number-one issue that every police department has to have within their community. And so when we talk about that, there are two types of authority: there’s legitimate authority, which the community gives you as a form of trust. And when you lose that, then officers, as you’re seeing across the nation, are going to have to rely on statutory authority. And I think at that point you start to lose trust.

Here in San Antonio it’s not nearly as bad. And in fact, the crowd has diminished quite a bit, but the conversation is still going on, which is important. You know, what I’d like your listeners to know is that it shouldn’t feel like there’s a chasm between the police department and the community. I’d rather you look at it as if we’re all in one big boat in the middle of the ocean, but we’re all in this together. And we’ve got to understand that, if you feel like there’s a chasm between the community and the police department, then we’ve got to address this now. And how do we do that? Through education, through information, through social media, making sure that the community has all possible ways to be informed by the police department. And it needs to be more than just coffee with cops. You see these little programs going around, and I get it, and they’re important within small pockets of communities, but on a national level, this has to be addressed. So I think procedural justice really is the key to solving a lot of these issues.

It shouldn’t feel like there’s a chasm between the police department and the community. I’d rather you look at it as if we’re all in one big boat in the middle of the ocean, but we’re all in this together. And we’ve got to understand that, if you feel like there’s a chasm between the community and the police department, then we’ve got to address this now.

AS: Thank you.

So I hear a lot of this today: “If you’re going to change culture around the use of force today, you have to have continuous training, systems of accountability and consequences.” Could you talk about these three separate issues of recruiting, hiring, and training? What you would love to see, and what hasn’t gone so well, historically speaking?

JS: So I realize I’m the anomaly, but is it a great idea to target military veterans to come do this job? I don’t know. I don’t know that there’s been enough data or argument on either side of this, right or wrong. I think that it’s possible, to be sure, because I believe that nothing is a one, right in social science. It’s hard to guarantee any specific outcome when you’re talking about human behavior. And so I’ve proved that you can come from a Marine Corps, military unit that’s been deployed in combat and then go into law enforcement and have a successful career and join a specialized unit like mental health that’s pretty progressive and deal with people and meet them where they are.

So it’s possible. But I also know that there’s the perception or optics of fear about it. What if we’re getting people from the military that maybe aren’t well? Maybe there are some psychological issues that they haven’t fleshed out, they haven’t dealt with. And so now they’re coming in and they’re still in this kind of hypervigilant, paranoid state that just carries over from their enlistment in the military. And so I think that needs to be looked at on both sides. But again, what I mentioned earlier about these recruiting videos, just look at how we’re targeting people, the type of message that we’re sending when we’re putting out these videos. Because what we’re saying is that doing mental health, for example, isn’t sexy. We know what sells—this is why the shows like Live PD and Cops do so well, because people would love to just be a spectator in this profession.

They love to sit back and look at it and critique it and judge it and have commentary on it. And seeing cops getting into high-speed chases, get into foot chases, get into these situations where they’re having to use tasers on people. As a spectator, there’s a huge market of people watching that. It’s entertainment to them. And it breaks my heart because I feel like to me, this is sad. There’s nothing exciting about seeing a human being get tased or shot with a beanbag round out of a shotgun or having any level of force used on them. Because whether they’re committing a criminal offense, or they’re mentally ill, to me it doesn’t matter. It’s still a sad part of, this person is clearly communicating something, right? I believe everything in the world boils down to two buckets. One is love and the other one is fear.

There’s nothing exciting about seeing a human being get tased or shot with a beanbag round out of a shotgun or having any level of force used on them. Because whether they’re committing a criminal offense, or they’re mentally ill, to me it doesn’t matter. It’s still a sad part of, this person is clearly communicating something, right? I believe everything in the world boils down to two buckets. One is love and the other one is fear.

And I think that people, even when they’re committing crimes, it’s usually out of a necessity, and people aren’t going to love that or agree with it. And that’s okay, but they’re either doing it out of opportunity or necessity. Or it’s based on trauma and people don’t take enough time to ask the questions of why.

And then when we talk about training, I think we create the problem in training. And again, I am notorious for saying things that people don’t really necessarily love, but here’s my belief: People show up to this profession with really, really good intentions. Why do you want to be a police officer? Those answers are coming from that person’s heart or their mind. But I believe that they actually believed them. I want to serve my community. I want to go help the community. I want to give back. I want to do all these things. But what happens is, they then go into this very high-speed training that really focuses on stress inoculation and stressing them out. And I believe that most police officers graduate from their academy paranoid. And if that’s offensive to some, then I’ll just say for me, myself, I’ll tell you this. I was probably more afraid graduating from the police academy than I was graduating from the Marine Corps boot camp. I felt prepared for the Marine Corps boot-camp graduation. For this it was like, “Jesus, I feel like I’m about to be deployed into this war zone.”

And so you’re constantly on high alert. In my nearly fifteen years of doing this, I’ve never needed what I’m trained and equipped to do. I think that we have to be willing to have honest conversations about that. And let’s rely on the actual data. Let’s rely on the fact that, I believe, in 2019 we had 59 police officers killed in this country by some felonious act. Fifty-nine killed. There were more in car accidents, whether in chases or just on their own. But let’s just say: at the hands of another person, we were killed 59 times, and we had 228 officers kill themselves.

So why is the focus not on individual wellness and self-care? Why is the focus of training, not on better preparing how to be a human being? Because here’s what we’re taught, how leave your work at work and your home at home. You have to learn how to turn your emotions off. Really? How can you be a human being and connect with another person if your emotions are turned off? And so I think that there’s a whole lot that needs to be looked at and done when we talk about redoing training. Because I feel like we create the problem in training, and there’s such a better way to do it.

Why is the focus of training, not on better preparing how to be a human being? Because here’s what we’re taught, how leave your work at work and your home at home. You have to learn how to turn your emotions off. Really? How can you be a human being and connect with another person if your emotions are turned off?

AS: Ernie, when you and Joe both have helped in training or led trainings, it’s very interesting to watch the facial expressions of the young cadets. They look both uncomfortable and a bit suspicious of your whole approach. How do you engage in profound mindset change, and also shift a lens? This issue of sight . . . gaining new sight as officers. How do you cultivate that more relational, humane sensitivity that is not embarrassed to communicate as much, but actually sees that sensitivity and emotional vulnerability as a core asset to fulfilling the mission of the role?

ES: Right. So, with cadets, it’s good that we can reach them where they’re at, at the moment. Because they’re very impressionable. You can really influence what their learning problem is. They’re also very robotic, so everything they’re taught, fine motor skills, how to draw a gun, how to shoot, how to do this, how to do that. They’re being given so much information in such a short amount of time and they know what they need to retain for testing. And then they know “Hey, I can put this on the back burner.” And sometimes that’s mental health: “Hey, I’ll put mental health on the back burner because there’s probably not a whole lot of test questions [on that].”

So Joe and I talk a lot about mindset with the cadets. Do they have a fixed mindset on how it’s going to be when they get out in the community? “I’m going to enforce these laws no matter what”—this is how I’m going to approach each issue. Or are you going to have a growth mindset? Are you going to actually take a step back and look at another individual’s perspective? Because it’s very common for a police officer to show up and provide a basic service to the community, but not add any value that would increase trust with that community. With the conversion, “aha” moment you’re describing, I see it more with the veteran officers that come to the training. And at the end of the week, they’ll come up to us on the side and confess quietly, “Hey, to be honest with you, I wish I had this training twenty years ago.”

Do they have a fixed mindset on how it’s going to be when they get out in the community? “I’m going to enforce these laws no matter what”—this is how I’m going to approach each issue. Or are you going to have a growth mindset? Are you going to actually take a step back and look at another individual’s perspective?

They understand; they get it now. They know a little bit more about mental health and, yes, the power of relationship than they did at the beginning of their career. And by listening to the families come and talk about how their loved ones have suffered with mental health, their eyes are opened. For so many it just hasn’t been part of their world. There’s nothing criminal about mental health, but so many officers are taught that you only enforce the criminal part of the law. You don’t get involved with any civil matters. Well, the issue is, yes you must, because mental health is a civil matter when we’re talking about an involuntary detention or whatever. But you need to be familiar and understand that that’s going to be part of your job. And as we see an increase in mental health [disorders], they’re going to need to be more proficient.

And that comes down to, are they competent? Do they know what they need to know about mental health? Are they compassionate? Are they willing to take a step back and look at it from a different perspective and look at the best outcome? And will they use common sense instead of just, this is a black-or-white issue. Will they use common sense to make the best decision possible for a good outcome for the community? This is the question they need to ask themselves. When we’re talking about training, I see better outcomes with the veteran officers because we don’t get to see the end product with the cadets until they come out and work the streets for a little while.

Ernie Stevens and Joe Smarro. Photo by Matthew Busch, 2015.

AS: How do you two cultivate the strength to stay sensitive to pain and not close up while still being steady when you need to be? What are your rhythms? What are your supports? What facilitates and sustains your long obedience in the same direction?

JS: For me, it’s having a really good therapist. So I am a huge advocate of therapy. I believe that every police officer in this country should be mandated to go to therapy yearly. And just for no other point than to check in. Again, it’s not to create an “I gotcha” moment. It’s not to further the stigma, because if the expectation is that we’re going to be human beings on our job, then we need to accept the fact that we’re going to be affected by our job. And so we have to be willing to provide resources specific to us officers as well.

If the expectation is that we’re going to be human beings on our job, then we need to accept the fact that we’re going to be affected by our job.

And so I go to therapy every month. And to me, that’s one of those unique things, too: some of the best police officers in the country are the ones who don’t just rely on learned experience to get across to someone. But they couple that with lived experience. And they allow themselves to open up and be seen to connect with someone. And it’s really not that difficult. What I love about it is that it is a concept that is teachable. Because people believe that you either have it or you don’t. And it’s just not true. Because yes, there are times where it can get heavy and it’s a lot to carry. I refer to it as the moral injury. People will call it burnout, compassion, fatigue, whatever. But really, I think that again, if you go back to why you’re doing this in the first place . . .

Even for me, I never wanted to be a police officer. It was just like, “Oh, this is a job I’m going to take.” And then I learned through doing that of what was my niche? Where am I going to most excel? And then luckily mental health came along. But even in that I have to check in with myself and say, “I don’t want to be a hypocrite.” And I was for so many years. For the first probably six years I was on the unit, I was a huge hypocrite. I was going out every day telling people what they need to do in their lives, how they can serve themselves, what they could do to solve their problems. And yet I was dealing with my own personal struggles, very, very deeply, not taking the advice I was giving other people.

And I feel like that happens so much in this job. We show up, because we almost have this persona that we create when we go to work. And so we show up as an officer or a something other than what you are. And you just tell people throughout the day what you should do, how you can solve your problems, how you can fix your problems. And yet you can’t even look at yourself in the mirror because you know you’re not doing these things that you’re telling other people to do. And so I got to a point where I was like, “You know what, I need to start living this out.”

That’s why I created the wellness class for first responders this year. It’s completely based on things that I personally have gone through and experienced. And it’s based on what has helped me or what I’ve seen for other people. And I use it, again, not based on theory, an idea, but rather on true lived experience. On Tuesday of this week, I had this guy who has served for thirty years who I didn’t know come up to me afterward with four other police officers standing there. And they were young. They had two years on or less. And he goes, “Joe, in my thirty-year career, I’ve never been through a class that’s touched me the way that this one did. You just took my entire career and made it all make sense to me. And I can better understand why I feel the way I feel. And I have hope of how to move forward.”

AS: Wow.

JS: The younger officers heard that and one of them came up to me and said, “Hey, I would love it if you would mentor me. I loved everything you were saying, and I’m wondering if I should start looking at other job opportunities or doing something else. What do you think about that?” And I was like, “Right on.” And so I think from both ends of it, people are really starting to open their mind up to, “What is my calling? What is my purpose?”

One of the problems with law enforcement is that we get in and we start to feel trapped. We get stuck by the idea of benefits and pension and the end road. A decade ago you never heard of someone leaving before thirty years. And now people are leaving with two years, five years, ten years, fifteen years, pre-pension. And it’s like, “You know what? This has evolved around me. It’s no longer for me. I’m going to go do something else.”

ES: I think Joe’s exactly right when it comes to self-reflection. You have to do that. You have to take a step back, but also understand that. . . . I love a quote that I read from Andy Harvey in his book Excellence in Policing. He says that wearing a uniform doesn’t separate you from the community, [it] makes you more of a part of it. So when we have an officer killed in the line of duty, we have so many people from the community who will stand out on the side of the road, they’ll hold flags. There’s such an outpouring. And to get a true sense of community and exactly who we serve, why shouldn’t we hurt when somebody in our community gets injured? We need to be a part of that. Community, like he says In his book, it’s common and unity. It’s the two things that when you put them together that we all have in common.

Wearing a uniform doesn’t separate you from the community, [it] makes you more of a part of it.

And if you can avoid the cynicism, which is difficult because as you know, the longer one’s in law enforcement, the more cynical one can become because we’re used to getting lied to, we’re used to . . . We see the worst of society because that’s when we’re getting called. It’s not when things are good, it’s when things are bad. So trying to avoid cynicism, taking a step back with self-reflection. Joe talks about therapy. I rely very heavily on my faith. We have coping mechanisms in place to help us. But at the end of the day, we are human, and we do struggle and especially with what’s going on now, it creates a lot of confusion in law enforcement. You just heard Joe say a thirty-year veteran’s like, “You know what, I think I may try something else.” That’s not an uncommon thought process that we’re hearing from officers.

They’re retiring at a younger age, they’re getting out, a lot of them, before the retirement age. So are there coping mechanisms in place to help from these types of burnout? Are you able to self-reflect and really take care of your needs, take care of your mental health? I’m so proud of Joe and what he’s doing with his wellness classes and resiliency classes this year at in-service. The only thing that was frustrating about it was when COVID-19 hit, they had to cancel classes for several months. So now we’re trying to play catch-up because this is such an important class, and he’s done an incredible job putting this together. And I really think it’s going to be pushed to the forefront.

AS: Wow. Well done, both of you. I’m deeply encouraged to hear that, from both of you.

You both have invoked a sense that there is hope in this renewed reckoning with race and police brutality, but it doesn’t seem like a foregone conclusion that we will necessarily feel that hope. What do you think is needed? What could tip the balance toward hope incarnated, and what action or inaction could tilt it in the opposite direction?

JS: That’s a tough one. I feel like if I knew that answer, I would be in a much better position in the world. Here’s I guess the best I can do for it right now, off the cuff: again, being willing to have difficult conversations. I would say, honestly, education is such an important piece of this. I’ve taken it on myself just because I’m curious. And I tell people, it’s not . . . If anyone’s seen the film or not, or if they know of me, you don’t have to identify yourself and say, “Hey, I’m a white man.” But I think what’s important about that is for me to say, “Hey, as a white man, I also admit the fact that I have blind spots. I admit to the fact that I have probably at some point in my life been a part of the problem.”

I think what’s important about that is for me to say, “Hey, as a white man, I also admit the fact that I have blind spots. I admit to the fact that I have probably at some point in my life been a part of the problem.”

I heard something beautiful this morning when I was consuming some content. And it was like, “Hey, it’s not about being a racist or not being a racist. It’s about actually being strongly opposed to racism.” And what that means is standing up for and not just saying, “Well, I’m not a racist. So this doesn’t really affect me or impact me.” It’s about being more than that. Just because you’re white doesn’t mean you’re off the hook. In fact, it puts you on the hook that there’s a greater expectation that we are going to be a part of undoing what history has shown and demonstrated that we have absolutely created. And it’s never been fair for the black community in this country, ever. I’m a believer that there’s never going to be true equality only because I think equality, also a part of that, is skills. And I think there’s just always going to be people who are better skilled at something than someone else.

But when it comes to like race . . . So even one of my blind spots, I used to be like, “I had a terrible life. I grew up with terrible traumas. I have a nine on the ACT. Abuse of all kinds starting at seven years old. I’ve had a terrible life, and yet I’ve made it out.” But here’s the difference, and I never saw it like this is, yes, while I’ve had struggles, none of them have ever been because of simply the color of my skin. And it was like, “Damn,” that really checked me and put me in my place of like, “Yeah, you’re absolutely right. I’ve had choices and opportunities afforded to me at a much probably simpler rate because my name is Joe and I’m a white guy.

And so allowing myself to be educated, watching things like 13th, watching different content, consuming things that helped me be more, I guess, understanding of why the problem is the problem. Even with slavery, it was like, “Oh, slavery has gone.” And then it’s like, actually, no. Who knew . . . And this is ignorant because I’m a cop, but who knew that actually the prison system is now just the new form of slavery? And it’s because many laws were created specific to the marginalized communities, to the black communities.

So then you can look at the voting problems. You can look at the fact that you’re getting . . . I had no idea that most of the potatoes coming from Idaho are on farms from prisons where it’s free black labor. So there are so many things that people just don’t realize that you’re a part of, because you are ingrained in this notion of, “I have privilege because I’ve never known what it was like.” So I think we have to, as white people, say, “Okay, I want to actually take the time and genuinely listen to you without being defensive, without being angry, without justifying anything. And just say, “Help me understand, because I wasn’t around when slavery existed, I wasn’t around during Jim Crow to understand it. So help me understand. And then how can we move forward? I want to be a part of this to help it out.” Because it’s not enough for me just to say, “Hey, as fifteen years as a police officer, I’ve never discriminated against someone. I’ve treated everyone, black, Hispanic, Asian, white, I’ve treated everybody fair and equal. Everybody. And my actions speak for itself.” But that does not, on its own, let me off the hook. Because absolutely I am still part of the bigger problem. And so I want to better understand it so I can be a part of the solution to move forward.

It’s not enough for me just to say, “Hey, as fifteen years as a police officer, I’ve never discriminated against someone. I’ve treated everyone, black, Hispanic, Asian, white, I’ve treated everybody fair and equal. Everybody. And my actions speak for itself.” But that does not, on its own, let me off the hook. Because absolutely I am still part of the bigger problem. And so I want to better understand it so I can be a part of the solution to move forward.

ES: Yeah. I feel, with any crisis, I’m very optimistic that good will come out this. Like Joe said, if it’s with conversation or education, it has to be had. If each officer would just manage the details of every citizen encounter, while managing his or her own stress, his or her own fatigue, we will see so many better outcomes.

Truck drivers in this country. They’re only allowed to drive so many hours before they have to take a break and rest. We have so many officers that work double shifts and overtime. How do I know this? Because I’m one of them. So fatigue plays a huge role. Stress plays a huge role. And it’s not fair to the community if we’re not at our best. So I think a lot of what we need to do is self-reflect. What can we do to take better care of ourselves so we can be better prepared to manage the details of each citizen encounter regardless of race? We need to do a better job, and it starts with us. I’ll gladly take a responsibility for that. And I appreciate Joe’s comments. I think he’s spot on.

If each officer would just manage the details of every citizen encounter, while managing his or her own stress, his or her own fatigue, we will see so many better outcomes.

AS: “And it starts with us.” That’s a wonderful way to wrap this up. I just want to thank you both so much. I am as inspired by you as I ever was and humbled, illuminated, and encouraged, which, frankly, are much-needed gifts right now. And I just want to thank you for doing the work you do, and more importantly, how you do it and who you are. So thanks for joining us today. And I hope to see you again soon.

ES: Thank you, Anne.

JS: Thank you, Anne. I really appreciate it. And anyone listening, do not give up hope. We’re going to learn from this and we’re going to grow from this. No doubt. Thank you, Anne. Be well.

If you’re compelled by the hope shared here, please check out Ernie and Joe: Crisis Cops, an HBO documentary produced in 2019 by Jenifer McShane.