Oldham’s Moot

In his book The Year of Our Lord 1943, Alan Jacobs describes “the Moot,” a group established in 1938 by J.H. Oldham, following an international ecumenical conference on “Church, Community and State” that had met in Oxford in July 1937. Oldham “sought to mobilise a movement of both thought and action engaging with society on the basis of Christian faith,” and over the next ten years, Oldham’s Moot regularly convened a group of Christian and Christian-adjacent public intellectuals, among them T.S. Eliot, John Baillie, Donald MacKinnon, Alec Vidler, Michael Polanyi, and Karl Mannheim. The purpose of the Moot was to “cultivate a profound Christian humanism in the public life of their society.” “One can waste a great deal of time, in the present world,” wrote Eliot,

by disagreeing with people whose thought is really irrelevant to one’s own thinking. . . . What is valuable is the formulation of differences within a certain field of identity. . . . These are the people worth disagreeing with, so to speak. This I think we have in the Moot, and this we ought to keep.

Michael Polanyi said that these discussions “changed our lives.” Jacobs discusses the Moot and other thinkers close to it: C.S Lewis, Simone Weil, Richard and Reinhold Niebuhr, W.H. Auden.

As Anne and I have pursued this Breaking Ground project over the last year, Jacobs’s book has been a lurking presence in our minds. Could we, we wondered, face a crisis not simply as something to be survived, but as an occasion for courageous and imaginative, future-oriented reflection and planning? What, we wondered, was this year revealing about who we were? What exactly is this culture of ours? And how can we pursue a world that is better than the one we left behind in March of 2020?

Next Steps

We’ve spent this year commissioning pieces that have brought a Christian-humanist lens to those areas of our common life especially touched by the always-interesting 2020–2021 news cycle: political polarization; the fragmentation of social trust; the nature, use, and abuse of political authority; the possibility of solidarity between races and classes; the isolation and disembodiment that the pandemic seems to have so intensified; the horror of the way we treat our elders and the possibility of a renewal of the virtue of filial piety on a culture-wide level; the promises and dangers of medical technology. We tried to be responsive without being reactive. We tried to be practical, even as we sought to understand some of the deeper currents at work rather than propose a litany of policy prescriptions.

And in doing all this we have somehow attracted an extraordinary network of people and organizations, a network I do not see paralleled elsewhere. Theologically orthodox, these groups and individuals—American, English, and Canadian—are otherwise varied in their political approaches, theological stream, civil sphere, and civic mission. Thus they are also varied in the audiences they serve.

We find ourselves now with a body of work and an institutional structure that deserve stewardship. And the challenges that remain are stark. Our public discourse seems caught in purity tests, cancellation, and incomprehension; we have systematically refused what Oliver O’Donovan has called our basic duty to each other:

not, as such, the obligation of a subject specifically, but the obligation of a member of society, something owed to the neighbor before anything is owed to the ruler. This is the duty to preserve the public truth of social engagements by exercising candor in the public realm, a candor which necessarily includes appraisal of the conduct of political authority. . . . Yet free speech can only be encouraged, not conferred, for free speech is a participation in the word of God, not a privilege which one form of constitution may confer, another refuse. Neither is it a “right” that one citizen may claim, another forgo. That would imply that only the private citizen who exercised it had an interest in it, whereas candor is of the greatest importance for the public realm itself. Candor is simple public duty, often underperformed, often performed badly, out of simple reluctance to take responsibility for the truth on which the community depends.

This is the duty that the Breaking Ground network will seek to promote. We believe that there is a great need for just such a network to help Christians working in various areas of society to think through and make decisions for action that draw from the deepest wells of the Christian humanist tradition.

What is this tradition? Christian humanism, born out of the ferment of the Renaissance, combined the Quattrocento’s renewed interest in classical scholarship and the nature and possibilities of humanity with a profound commitment to the reality and centrality of the Christian faith. Influencing both the Protestant Reformation and the Counter-Reformation, it fostered an explosion of scholarship, imaginative and didactic writing, ethical reflection, investigation of the natural world, visual art and architecture, music and education, as well as new social forms and the renewal of personal piety. In its civic form, it sought to bring these goods into the public sphere, shaping political structures and the minds of rulers, as well as conferring new honor and responsibility to the office of the citizen.

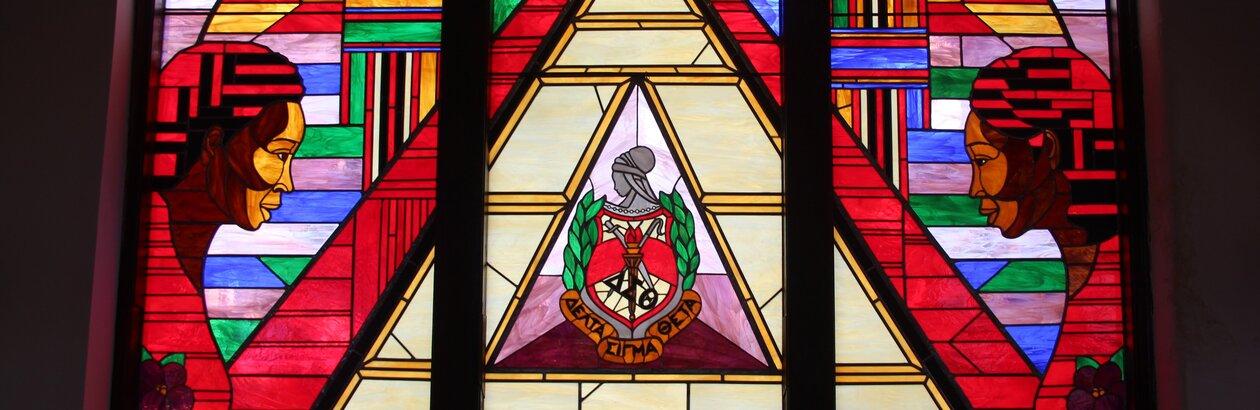

Madonna and Child by Sandro Botticelli, 1468. One of the paintings of the Quattrocento period.

This is the tradition from which we’ve drawn inspiration and which we have sought to water for a new bloom in our time. So what’s next? Well, for one thing, while our public-facing publishing venture is wrapping up, the Breaking Ground network of institutions and the leaders stewarding them will continue to meet together to have these conversations; I encourage you to follow the work of, and consider becoming involved with, any one or more of our partner organizations.

I encourage you also to seek out the conversation we have been having in these pages where it is continuing: in Comment, Plough, and The Trinity Forum, and also in the pages of a new crop of humanist and Christian humanist “little magazines” so ably described by Elayne Allen in her recent piece in these pages.

These magazines are, above all, institutions that serve as bridges between our contemplative and active lives: between the leisure that is the basis of culture and the practical reason aimed toward action that we must all use as we make choices in our private lives as family members and economic actors, and in our public lives as citizens.

These magazines also serve as hubs around which communities form: that dense network of friendships and conversations, writers and editors, scholars and churchmen, community shepherds and organizational leaders. This mosaic is the Christian humanist public sphere.

The Public Calling

This is not, we believe, an optional extra for human life and Christian discipleship. It is inappropriate for us to fail to participate in public life. Becoming a Christian means being able to be, more effectively, what humans always were supposed to be, what Adam was made to be, and what his progeny should have been after him: rulers under God over the created world, rulers of our own lives and households, full participants with full responsibility in the human project.

Becoming a Christian means being able to be, more effectively, what humans always were supposed to be, what Adam was made to be, and what his progeny should have been after him: rulers under God over the created world, rulers of our own lives and households, full participants with full responsibility in the human project.

And as both the Hebrew and Greek strands of our tradition testify, that project is in essence a political one: We are political animals. To be confined only to private life, to getting and spending or to the good of our households, as important as these things are, is to be only half human. Set free by Christ, we should not act like slaves who are denied responsibility for the res publica, the public thing. Made part of his ruling family, we should not act like private citizens.

This does not of course mean that all are called to hold public office. As O’Donovan puts it,

The duty of public candor is not a duty of public office alone. Subjects who hold no public office may discharge it by the way they tackle their business in the public realm, look to safeguard the common good in their commercial engagements, articulate and discuss the common good with those they deal with, not isolating themselves by technical narrowness or professional mystique, by advocating, justifying, listening to others’ advocacy and justification, seeking a common understanding and approach to common tasks, avoiding the sins of rhetorical exaggeration and administrative impatience.

But we are all called to be civic agents and caretakers: receiving, building up, and passing on this public world to those who come after us. And this will require a very different sort of public engagement—and private support—than the models of recent memory.

The Oppositional Stance

One of the things that Breaking Ground has addressed extensively over the last year, and that we must now push forward in grappling with, is the way that Christianity has conducted itself in politics.

Evangelicalism has done great good in the world, both the movement as it began in the eighteenth century in Great Britain, and the revival of that movement in the second half of the twentieth century in the United States. But the more recent version has had a culture problem, which is really an authority problem.

This new American evangelicalism understood itself as fundamentally not at the center of power or of intellectual life: it was made up, largely, of non-mainstream people who were not in the mainline churches and who wanted to reject the oppositional culture of fundamentalism without rejecting the tenets of the faith. It always had the uneasy sense that this might not be possible: it always had the flavor of attempting to create a just-as-good-as-secular-culture culture, to prove to the mainstream that it was not like its embarrassing fundamentalist uncles. It did not perceive itself as having authority.

This culture of supplication gave rise, in reaction, to certain problems among many of the evangelicals who supported Trump. It also gave rise to certain problems in anti-Trumpian evangelicalism. In both cases, there was a fundamental unease with power, a fundamental inability to perceive oneself as having authority: a kind of addiction to victimhood, to being the underdog.

This, combined with the pathologies in our political culture at large, has created four distinct political distortions. First, some Christians now perceive Christianity as little more than an interest group among other interest groups, the religious-industrial complex that jockeys and seeks rent alongside lobbyists from, say, the oil and gas industry—angling for “favors” from the state. Second, in an attempt to rebuke this squeamish instrumentalism, we see a growing affection for the suggestion that political involvement at all, let alone state support for churches, is bad for the church—as Nilay Saiya suggested recently in the pages of Christianity Today. (Saiya cannot seem to imagine a kind of Christian relationship to politics that is not as an interest group.) And then there is a third thing happening: a preemptive self-alienation, a bunker mentality or willingness to cry persecution, which prevails all too frequently on the right. Fourth, we see a desire to distance oneself from those “other” Christians, the embarrassing conservative ones, such that we can preserve our sophisticated relationships, our pristine calling to translate from the sacred to the secular, our Christian cosmopolitanism.

Christendom in a Pluralist Society

This all seems, frankly, sad and unnecessary. It’s just not the way normal human politics is ordinarily done, nor is it the way human culture is normally made. It’s perfectly possible to have an orthodox Christianity that understands itself to be at the center of making human culture, while interacting with non-Christians and their cultural products who are also at the center, and with a grounded sense of political responsibility: because that’s just what’s actually true. And it’s not as though this is the first time this has happened: This is the story of the roots of the church, of St. Paul in the agora, of St. Augustine in his study, of Hellenic philosophy and Judaic theology, of Roman playwrights and Hebrew prophets.

It’s perfectly possible to have an orthodox Christianity that understands itself to be at the center of making human culture, while interacting with non-Christians and their cultural products who are also at the center, and with a grounded sense of political responsibility: because that’s just what’s actually true. And it’s not as though this is the first time this has happened: This is the story of the roots of the church, of St. Paul in the agora, of St. Augustine in his study, of Hellenic philosophy and Judaic theology, of Roman playwrights and Hebrew prophets.

The work that Breaking Ground has been a part of is simply this work: continuing the work of Oldham’s Moot, of that midcentury Christianity which itself has roots that, age by age, reach back to the very beginnings of our faith, of our civilization, of the world that God created and redeemed and that we are called to form and fill.

The thing is, this is all very natural. Our culture is inescapably woven together with Christianity. Whatever cultural work we do, whatever political projects we pursue, whatever scholarship we do, whatever art we make is in profound continuity with the past five thousand years of mainstream human cultural life. It is (one might gently point out) the secularists who are out of place, using words and depending on ideas whose origins they do not know, living and working in buildings built by those who share our faith. They too, though, are carrying out Adam’s task, aided by common grace, and if we somehow think that we can’t or shouldn’t work in cooperation with them toward the good—tell that to Aquinas, as he cooperated with Aristotle. This is the common human project that we’re engaged in, together. We don’t need to be anxious. We just need to carry our work forward.

The anxiety that refuses to do this, and which gives rise to all four distortions of Christian political life I mentioned above, has a particular name. Its name is pusillanimity. It is thinking oneself less able, with less authority, than one in fact has. It is being self-marginalizing, self-emasculating.

We don’t need to be anxious. We just need to carry our work forward.

Pusillanimity must be refused: it is in fact a vice, though one often disguised as the virtue of humility. It must be refused in part because those who are pusillanimous are dangerous: they don’t believe they really have authority, and so they can only imagine using power for their own private gain, or for irresponsible schemes, and they are afraid of losing it. Like a rageaholic who screams because he feels he is unheard, if they do have power they may hurt others with it through not knowing their own strength; if the pusillanimous person is a Christian in a pluralist society, he may forget the actual purpose of politics and seek to govern for the benefit of Christians as a kind of interest group, as opposed to the general good. This is a recipe for disaster in a person and in a state.

Magnanimity

The corresponding virtue to the vice of pusillanimity is, of course, magnanimity.

How can we claim, as Christians, that magnanimity is anything but one of what St. Augustine called the “splendid vices” of the pagans? Aristotle defined μεγαλοψυχία, megalopsychia, greatness of spirit, as “claiming much and deserving much.” This sounds impossible to square with humility, and with being followers of the Lord, who “did not regard equality with God as something to be grasped.”

But St. Thomas tells us that, indeed, magnanimity is a virtue. He gives it a subtle twist, however—and with that twist he throws the whole of human life into proper shape. “Magnanimity,” he writes,

by its very name denotes stretching forth of the mind to great things. . . . Since a virtuous habit is denominated chiefly from its act, a man is said to be magnanimous chiefly because he is minded to do some great act. . . . An act is simply and absolutely great when it consists in the best use of the greatest thing.

John Witherspoon, building on Aquinas’s rescue of this virtue, preached a sermon to the 1775 Princeton graduating class that is one of the most thoughtful and thorough treatments of Christian magnanimity that I know of. As we seek to mend what has gone wrong in the relationship of Christianity to our public life, and to move forward in our public calling, I can think of few better guides.

His text was from 1 Thessalonians: “For you know how, like a father with his children, we exhorted each one of you and encouraged you and charged you to walk in a manner worthy of God, who calls you into his own kingdom and glory.”

The virtue of magnanimity, says Witherspoon, is what leads men

to attempt great and difficult things, to aspire after great and valuable possessions, to encounter dangers with resolution, to struggle against difficulties with perseverance, and to bear sufferings with fortitude and patience.

The Magnanimous Multitude

Winthrop also, in a way, “democratizes” that most undemocratic of virtues, as Christianity itself democratizes Aristotelian eudaimonia, opening its gates to women, to slaves, to the sick and the poor and those otherwise sadly lacking in an Athenian private income or a Roman latifundium.

We are to live according to our station (he would say) but in every station, we may live nobly. I’d push back against what sounds like the more rigid aspects of this formulation: an auto mechanic’s daughter may obviously get a philosophy doctorate; a banker’s son may read too much Wendell Berry and apprentice himself to a farmer. But his point remains, and that point is at its best not that different from Freddie deBoer’s in his recent Cult of Smart: there are different kinds of ways of living a good human life, and not everyone need aim at a tenure-track position at an Ivy – or a seat in the Senate.

Magnanimity will spur us to greatness but keep us from a mean grasping, as well as from having contempt or bitterness toward those whose place in life is not ours. It will not create pride or overweening ambition, but will make men “active and zealous in the duties of that place in which they already are.” Each of us, by our rational nature, our descent from Adam and reception of the creation mandate to make civilization, has a high enough birth to exercise this virtue—or to fail in it. Each of us, by our adoption in Christ, has been given an even greater scope. “When a prince, or other person of the first order and importance in human life,” Witherspoon says,

busies himself in nothing but the most trifling amusements, or arts of little value, we call it mean, and when any man, endowed with rational powers, loses them through neglect, or destroys them by the most groveling sensuality, we say he is acting below himself. The contrary of this, therefore, or the vigorous application of all our powers, and particularly, the application of them to things of moment and difficulty, is real magnanimity.

Nor will magnanimity drive us to refuse obedience, refuse the call of just authority. It is not the magnanimous soul that says “no gods, no masters.” In his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, John Henry Newman writes that we must seek to vanquish “that mean, ungenerous, selfish, vulgar spirit” which is a corruption of our nature, and which,

at the very first rumour of a command, places itself in opposition to the Superior who gives it, asks itself whether he is not exceeding his right, and rejoices, in a moral and practical matter to commence with scepticism.

Nor will it lead us to refuse to recognize excellence not our own: this is not self-aggrandizement but very nearly its opposite. Magnanimity has room for others, for their good, for a delight in their excellence. It is above all not envious. Because it has this spaciousness in it, it is entirely compatible with—even requires—humility, and the willingness to be delighted by the world; indeed, St. Thomas tells us that humility and magnanimity are paired virtues, each according to right reason helping us to act well, with wisdom, in the world.

The Duty of Desire

Magnanimity defeats irony-poisoning and the cynicism that keeps us from full engagement with life. Pusillanimity is closely related to the vice of acedia, of the boredom or apathy that refuses to be interested in the interesting, or to acknowledge or treat the worthwhile as worthwhile. In The Last Battle, the tide has turned: Eustace has fought off two Calormene soldiers who have kept a group of Dwarfs captive. “Well struck!” King Tirian says. “Now, Dwarfs, you are free. Tomorrow I will lead you to free all Narnia. Three cheers for Aslan!” But the Dwarfs refuse—they refuse both to believe that they are really freed, that there is an Aslan to follow, and they refuse the call of high service, to help free others. “We’ve been fooled once, and we’re not going to be fooled again. . . . The Dwarfs are for the Dwarfs.” This cynicism is what magnanimity refuses.

Witherspoon goes so far as to say that in fact it is only those who have received the gospel who can be truly magnanimous: that only in Christianity can greatness be wedded to goodness, and classical arete to the theological virtues. His reasons for this are striking. “A great mind,” he says,

has great capacities of enjoyment as well as action. . . . The large and increasing desires of the human mind, have often been made an argument for the dignity of our nature, and our having been made for something that is great and excellent.

Witherspoon—and Christianity itself—offers an answer to desire, and to suffering, remarkably different from the Classical Good Life Emergency Backup Philosophy (i.e., stoicism) does. Stoicism teaches us to desire less, to accept loss and death. Christianity teaches no such thing.

The greatness and excellence that we properly desire with the desire that is part of magnanimity—what human ambition could satisfy this? What empire could quench our thirst? What noble deed could be noble enough? Above all, what human task of city-building is glorious enough to satisfy our desire—unless that task is caught up in the building of the new Jerusalem? And what ruler is glorious enough to satisfy our desire for someone glorious to follow—unless that Ruler is the King of Kings?

Too, it is only Christian magnanimity that contains within itself the best medicine against the danger of magnanimity’s distortion into pride: What do we have that we have not received? All that we have, the very image of God in us, is a gift. We will not refuse to perform Adam’s civilizational and regal task, but we will never forget that we rule by gift-right, and by adoption.

Meta-virtue

We must aim, Witherspoon says, at what is really valuable, to do the most good, and in that exercise all the skill, all the courage, and all the diligence that we can. But skill, courage, and diligence alone are not enough—else, he says,

a rope-dancer might be a hero: Or if any person should spend a whole life, in the most unwearied application of accumulating wealth, however vast his desires, or however astonishing his success, his merit would be very small.

To be magnanimous is to aim to do not a little good in the world, but a great deal of good, and to have those powers to actually get that good done. This is not a matter of personal gifts precisely: one may be naturally gifted in many ways, but fail to improve these gifts. Magnanimity is the virtue that leads one to want to cultivate the other virtues, to want to become virtuous, to want to become powerful and effective in doing good. It is in that way a kind of meta-virtue, or sum of the virtues.

And to be both accountable and effective, the magnanimous person must not be a lone wolf. We must seek counsel, seek those friends who will spur us to excellence and check us if we slip into pride, and seek to be part of groups—like the Moot—that will draw us together with those who will challenge us when we should be challenged, who will help us and whom we can help, who will remind us that the reality of politics is, and always remains, friendships. These groups, formal and informal, which the jurist Johannes Althusius, writing in 1603, called collegia, are, along with natural families, the basic building blocks of our social world. The network that they form as they overlap and interpenetrate is what we call civilization. One might think of it as the root structure along the bank of time, channeling the power of its flow and preventing its dissipation into impotence, or its rage in a flood.

And in all of this, magnanimity must never conflict with other virtues. As Witherspoon reminds us,

The object of our desires must be just as well as great. Some of the noblest powers of the human mind, have often been exerted in invading the rights, instead of promoting the interest and happiness of mankind. . . . Our desires ought to be governed by wisdom and prudence, as well as justice.

The Tribe of the Eagle

It is a sobering warning. Witherspoon was, after all, part of that founding generation of whom Lincoln, in his Lyceum address, said that they sought to make their names great in establishing a country to test the “capability of a people to govern themselves.” Whether or not one believes that the founding generation was magnanimous in the full Christian sense of the virtue as Witherspoon describes it, and whether or not the war they fought was just, the rest of Lincoln’s warning Witherspoon would most heartily have echoed:

It is to deny, what the history of the world tells us is true, to suppose that men of ambition and talents will not continue to spring up amongst us. And, when they do, they will as naturally seek the gratification of their ruling passion, as others have so done before them. The question then, is, can that gratification be found in supporting and maintaining an edifice that has been erected by others? Most certainly it cannot. Many great and good men sufficiently qualified for any task they should undertake, may ever be found, whose ambition would inspire to nothing beyond a seat in Congress, a gubernatorial or a presidential chair; but such belong not to the family of the lion, or the tribe of the eagle. What! think you these places would satisfy an Alexander, a Caesar, or a Napoleon?—Never! Towering genius distains a beaten path. It seeks regions hitherto unexplored.—It sees no distinction in adding story to story, upon the monuments of fame, erected to the memory of others. It denies that it is glory enough to serve under any chief. It scorns to tread in the footsteps of any predecessor, however illustrious. It thirsts and burns for distinction; and, if possible, it will have it, whether at the expense of emancipating slaves, or enslaving freemen.

This kind of greatness, Witherspoon would say, is precisely the pagan counterfeit of the real thing.

Self-Command and the Public Good

So how does this play out in our lives? Witherspoon gets specific. “Religion calls us to the greatest and most noble attempts, whether in a private or a public view.” In private, in the interior of self-command, is true greatness. As Solomon wrote, “He that is slow to anger, is better than the mighty, and he that ruleth his spirit, than he that taketh a city.” This is a matter of, as Winthrop says, resisting “corrupt and sinful passions,” but it is also a matter of directing one’s passions. The rule of one’s spirit is not its quenching, and the harnessing of one’s spiritedness to the real good of oneself and one’s community, is the real battle, and he who achieves it has conquered truly. It is an embarrassing fact of our culture that the language of self-rule has been replaced with the language of self-management: every man his own HR department.

It is an embarrassing fact of our culture that the language of self-rule has been replaced with the language of self-management: every man his own HR department.

In public, “every good man is called to live and act for the glory of God, and the good of others. Here he has as extensive a scene of activity, as he can possibly desire.” What we have been given, in Christianity, is something truly worthwhile—to glory in God and to build his kingdom. Compared to this, to build what Winthrop calls “altars to our own vanity,” seems the real pusillanimity. We serve a truly great king, one who is worthy of every possible exertion and hazard we can bring to his service. We should pity those who, though they are in some ways magnanimous, don’t have the gift of a proper aim, a proper ambition, for their magnanimity. Part of being magnanimous is having something truly worthwhile to do, and that, he says, is what the pagans did not have.

In Pursuit of the Common Good

How is this related to politics, and to the public sphere? Here we must turn from John Witherspoon to Charles de Koninck, and his dispute with Jacques Maritain.

Maritain is, along with Lewis and Sayers and Eliot, one of Jacobs’ key figures. De Koninck did not make the cut, though he should have. In his discussion of their debate, Chad Pecknold notes again that strangeness which Jacobs notes, and which Anne and I found so inspiring in our work at Breaking Ground: “It may seem odd that a theoretical dispute would emerge amid world war, but it’s precisely in times of crisis that people find urgent incentives to re-examine first principles.”

And it was, indeed, in the year of our Lord 1943 that de Koninck published his essay “The Primacy of the Common Good Against the Personalists.” In it, he criticizes the idea, popularized by Maritain, that the individual human person is the fundamental unit of society, and that the primacy of the human person provided the best check against the totalitarianisms of Right and Left then in the process of shredding the world.

This is not the case, says de Koninck. The common good is not the collection of the private goods of individuals, which, if put to it, we could enjoy alone: a piece of birthday cake, a bouquet of lilacs. Rather, common goods are those that we can only enjoy with each other: the good of being a daughter, a wife, a mother. The good of being a friend. Common good has, as its glue, love, and the exchange of justice and friendship that makes us truly human. As de Koninck points out,

The good of the family is better than the singular good, not because all the members of the family find in it their singular good: the good of the family is better because, for each of its individual members, it is also the good of the others.

We experience the love of our families, and our love for our families, as a delight. But it is a delight that is profoundly unlike the delight we have in cake, or even in private aesthetic experience. When I love my brother, I don’t just enjoy his company—though I do. I also desire his good, very deeply, and even if somehow I weren’t able to have his company, I would never lose the desire for his good. And it is a love that perfects us, that makes us better—it can’t help but do so.

Common good has, as its glue, love, and the exchange of justice and friendship that makes us truly human.

To Seek the City’s Good

We all feel this instinctively to be true: we’ve experienced it, at least to some degree. What de Koninck reminds us of is that fundamentally politics is about the same thing, the same exchange of love and justice—of what Althusius referred to as “symbiotic right.” Political love, the political common good, is less cozy than familial love, and does not replace it—but it is the same kind of thing, though grander and more stately. Our love of our polity—our city, our nation, the community of nations—and our care for these public bodies, and the public good, also perfects us, drawing us out of ourselves, drawing us to great things. As Pecknold writes,

God made the world good—and very good. His goodness is diffused throughout the whole of creation. So the greater the common good, the more goodness it communicates, and the greater our love should be for that good—up the scale of goodness to God himself, who is the uncaused cause of all goodness.

What does it mean to love the city’s good? De Koninck quotes St. Thomas:

To love the good of the city in order to appropriate it and possess it oneself does not make a good politician, for it is thus that the tyrant too loves the good of the city, in order to dominate it, which is to love himself more than the city: in fact it is for himself that he desires the good, not for the city. But to love the good of the city that it might be preserved and defended is truly to love the city, and it is that which makes a good politician, so much that, with an eye to conserving and augmenting the good of the city, he exposes himself to danger and neglects his private good.

To love its good is of course to will that it be good. “‘My country, right or wrong,’” as Chesterton says, “is a thing that no patriot would think of saying. It is like saying, ‘My mother, drunk or sober.’” Of course one does not cease to love, but one wills that one’s mother be sober, one’s country be just.

Because the love of the city, the pursuit and experience of the political common good, is one of the things—like the love of one’s family—that perfects us. It was for the sake of the Jews also and not just for the sake of the Babylonians that God, through Jeremiah, commanded them, “Seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.” Even out of Jerusalem, they were political animals. Even before we enter into the new Jerusalem, so are we.

And though here we have no abiding city . . . neither, let us remember, did the ancients. Polybius wrote that at Roman funerals, honored statesmen of the past, those who had done great good for their city, were represented by men of like height to them, wearing masks that resembled them, whose good deeds for the city were recounted beginning with the most ancient. “By this means,” he wrote,

by the constant renewal of the good report of brave men, the celebrity of those who performed noble deeds is rendered immortal, while at the same time, the fame of those who did good service to their country becomes known to the people and a heritage for future generations. But the most important result is that young men are thus inspired to endure every suffering for the public welfare in the hope of winning the glory that attends on brave men.

And that was the best spur on offer for Roman magnanimity: if you exerted yourself for the sake of the Eternal City to great deeds, perhaps (accounts differed) your shade would have a high rank in the Elysian fields, and a young man might wear a mask of your face while your deeds were recited before the assembly. But your shade is not exactly you, any more than the mask is you.

We have not just a better spur, but a better spur even on Roman terms. Allowing our citizenship in our own cities here to prepare us for and open us into our citizenship in the new Jerusalem: that is food for the magnanimous soul indeed. “Do you not know that we are to judge angels? How much more, then, things pertaining to this life!” This is St. Paul’s exasperated cry against pusillanimity. And we seek the praise not only of our descendants, but of God himself.

Witherspoon says that he is not “able to conceive any character more truly great than that of one, whatever be his station or position, who is devoted to the public good under the immediate order of Providence . . . he complains of no difficulty and refuses no service, if he thinks he carries the commission of the King of Kings.”

In the order of nature, the greatest good we can do is to serve God by serving each other by seeking the true political common good. This is not as high a good as performing the spiritual acts of mercy, or fulfilling the Great Commission. But it is a good we neglect at our peril. We ought no more to refuse it than we ought to refuse to care for the members of our own household, or of the household of faith.

Gray-Market Public Sphere

And so we are called to the public sphere. But the public sphere we must operate in is, for Christians, a bit of a gray market these days. Secularization has meant that when we speak of public things in public places, bringing God into the picture can often be tricky.

But we will not close ourselves off from or take a hostile attitude toward “secular society” or the public world: this is the world that God has given us, and dismissing it or refusing to take part, or attempting to create a parallel “Christian public sphere” is not what we ought to do.

And so the institutions and publications that are Breaking Ground’s successors will foster what is notably lacking in our society: good conversation. Ironically, the humanist vision of debate and reason and charity—rejected even by some Christians as a cucked approach to a world at war—is what we can offer the secular world now. We can engage in truly good argument—not the simple-minded own-the-libs free-speechism of, for example, the Daily Caller, and not the vaguely posthuman and fundamentally materialist debates of Quillette.

Rather, we will foster levelheaded but passionate and interesting debates and writing in the Christian humanist tradition, keeping humanism and even the best aspects of liberalism alive (though founded on pre-liberal principles) when they have been abandoned by both the left and the post-Christian right.

And in our habits of conversation, our charitable reading of each other, our honesty and willingness to remain in conversation with those with whom we disagree, we must model for the increasingly polarized secular world what a public discourse looks like that does not rest on accusation, bad-faith readings, guilt by association, cancellation, and the blandest of contemporary certainties.

The Success of the Failures

What did the men and women of Oldham’s Moot do? According to Jacobs, not enough. They did not carry out on England a Christian version of the reconstruction of society that, for example, the United States carried out on Japan in the postwar years.

But Jacobs underestimates their work. They reshaped our public sphere as Christian intellectuals. We still live in the mental world they made, and our institutions reflect this: we are still building what they imagined; they are our teachers, and it is from them that many of us learned of those who went before them. They made the world bigger.

We need to become members of that public sphere and carry it on, making our own good-human work in a time when the Christian and secular worlds seem further and further apart, and in an age when Christianity, at least conservative Christianity, will (it seems likely) be ever more aggressively shut out of the public sphere because of its association with Trump. We must not give up normal, sunlit institutions where we can still have access to them—the universities, the mainstream press, nonprofits, philanthropy—but we must press on even where we can’t.

If we are called to the part of public service that is fostering and engaging in public conversation, it should not and cannot matter whether Christians are in the ascendency culturally, any more than someone who is called to a private life can only fulfill his duties when there’s a bull market. If you’re called to private life, you’ll do your best in whatever market there is. And if you know your work, and you understand the world, you’ll know that markets shift, and fortunes change, and the point is to do the work that is yours.

What keeps a man or woman who is called to public life out of it is exile—literal exile, Seneca’s exile, or Dante’s. None of us is in exile from our earthly polity. As long as we are able, what we’re called to do is to take responsibility, no matter what the current circumstances. That is our job. We can’t wait for easier or more straightforward times in which to express that political love. There are no other people who are ours, and no other time. And these things, too, are gifts.