In late April, crowds of people gathered at the Pennsylvania statehouse to protest stay-at-home measures taken in response to the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Parked out front of the capital was the cab of a dark green 18-wheeler with the words “Jesus is my vaccine” spray-painted on the side. The arresting visual stood as a statement of defiance. A statement of faith.

Over the summer, as the virus continued to spread, and as various phases of economic restriction and reopening waxed and waned, Christians expressed their resistance to state-mandated orders to wear masks and to limit the size of public gatherings, including church services. Prominent megachurch pastors like John MacArthur openly defied the law prohibiting large gatherings. Congregations across the country insisted on coming together unmasked and in person.

Many of these decisions, however ideologically fueled, have been espoused under the banner of faith with injunctions like “Do not fear,” “God is in control,” “We are spiritual beings before we are bodily beings.” Such ideas sound biblical. They can bring comfort. But in the midst of a pandemic that has disproportionately harmed and killed thousands of the most vulnerable within our society, these words express a theological complacency that distorts the rich mystery of divine sovereignty and human culpability, responsibility, and engagement.

Subscribe

And now, with an ongoing, ideologically charged economic and medical crisis comes a presidential election. Some people who profess faith in Christ will vote for Donald Trump. Others will cast a ballot for Joe Biden. Christians across the political divide will pray for God to appoint the leader who will carry out God’s way of justice and mercy. It will be tempting for those whose candidate wins to feel that their prayers have been answered. But as we enter into the uncertainty of this next week and perhaps months, we need to comfort ourselves not with a simplistic understanding of God’s control over human events but rather with a willingness to participate in the holy mystery of God’s steadfast love.

The Language of Control

Nowhere in Jewish or Christian Scripture do we read the exact words “God is in control,” but the idea does arise from biblical texts. At the end of Genesis, Joseph points out to his brothers that what they intended for harm God intended for good and for the salvation of many people (Genesis 50:20). Jeremiah famously assures the exiled Jewish nation that God has plans to prosper them and not to harm them (Jeremiah 29:11).

The Hebrew Scriptures are filled with promises of God’s ultimate redemption of the Israelites, even when the way toward that promised future is unclear and seems impossible. Jesus, especially in the Gospel of John, declares God’s utmost authority over the rulers of this world and of the spiritual realms. Paul assures his battered and beleaguered readers that “all things work together for good for those who love God” (Romans 8:28). In the book of Revelation, John paints a picture of a final judgment and a final glorious reign of Jesus in which “there will be no more night” (Revelation 22:5). It seems easy to conclude from the arc of the biblical narrative that God is, indeed, in control of both particular human events and the cosmic sweep of history.

But of course, we run into the age-old puzzle of theodicy. If God is all-loving and all-powerful, how could he allow the suffering and pain we experience and see all around us? Even more, why would that suffering be borne, consistently and disproportionately, by the most vulnerable human beings among us? These questions have been asked from time immemorial, and there are no easy answers.

Still, it is worth pointing out that from a biblical perspective, as much as the sweep of the narrative affirms God’s sovereignty, the emphasis does not land on God’s control of human affairs. Rather, the scriptural writers insist that the steadfast love of God will endure. The drumbeat of God’s love that sounds throughout the Bible calls for our pause.

It would be easy for me to say that God is in control of our situation, that God has ordained our life of relative ease. But if I were to comfort myself with that logic, it would lead to the less palatable thought that God also has ordained the lives of suffering and hardship many of my fellow Americans endure right now, to say nothing of those living in still more fragile societies around the globe.

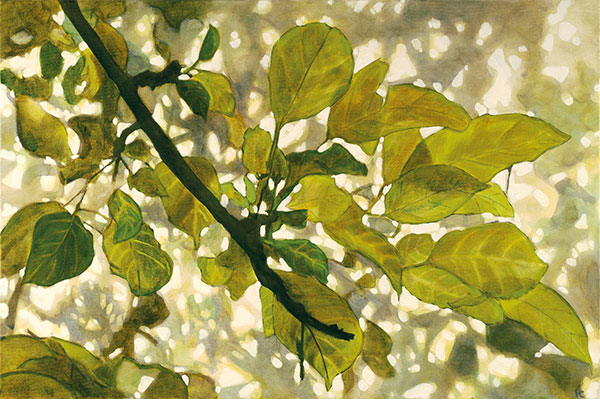

As I write, it is October in Connecticut. Golden leaves flutter and pile up outside my window on a heavenly day. Our three kids are all in the classroom full-time right now, unlike kids in much of the nation. We live in a small town, and that lack of population density means that the relative risk of contracting COVID-19 is low. As a family of educated and affluent white people, our health outlook fits our demographic profile. None of us has any underlying medical conditions. Even our daughter with Down syndrome is considered low risk for any serious effects from this virus. And if our schools need to transition to remote learning again, our house has enough rooms for each of our kids to claim their own space with a laptop or Chromebook to connect with teachers and friends online.

It would be easy for me to say that God is in control of our situation, that God has ordained our life of relative ease. But if I were to comfort myself with that logic, it would lead to the less palatable thought that God also has ordained the lives of suffering and hardship many of my fellow Americans endure right now, to say nothing of those living in still more fragile societies around the globe.

I am grateful every time I look outside and see the hills painted orange and the shockingly blue sky, every time I hear the river that rushes through the trees at the bottom of the hill that leads to town, every time I enjoy a warm cup of tea and the company of my husband or children. Yet in the midst of this genuine gratitude, I have also been learning not to confuse the privileges of my life with God’s blessings.

Facing Reality

Since March of 2020, millions of Americans have lost their jobs. People of color have been disproportionately infected and killed. COVID-19 has ravaged nursing home populations and prison inmates. Experts expect the suicide rate to rise, domestic violence to increase, and depression and anxiety to rise as well. Many kids from less prosperous communities are not attending school in person, do not have access to a Chromebook or internet connectivity, and do not live with parents equipped to stand in the gap as teachers by proxy. Millions of our most vulnerable students are receiving little to no education, and this situation could continue in some manner for the next year or beyond.

This crisis has revealed the injustices already at work throughout American culture when it comes to education, health care, and job security. If God is in control of these facts, it allows people like me to tacitly accept them as permanent fixtures of our social landscape, instead of recognizing the ways in which their lopsided treatment of human dignity offends the very being of God. It allows people like me to remain distanced from that injustice rather than actively wrestle with it. It exempts me from holy participation in God’s work to dismantle unjust structures, of which I could continue to be simply a beneficiary.

The Bible always complicates any easy rendering, including that of blessing and punishment. “Rain falls on the wicked and the righteous alike,” said Jesus after giving the world-changing Sermon on the Mount. The teachings and stories throughout Scripture push us beyond our culture’s default to reductionistic, individualistic judgments. The biblical writers push us toward a more interwoven, relational understanding of the Triune nature of a holy God of love.

And so we return to another set of questions. How can we understand God’s victory over sin and death in light of the ongoing suffering in our world? How can we claim God’s redemptive purposes without falling prey to theological passivity? On a time-bound level, how can we interpret the results of a national election as people of faith both vehemently defend and denounce opposing candidates? Is there a way to do this interpretation in faith that God is indeed sovereign and mysteriously guiding human affairs, not in some manipulative puppet show, but rather in love?

Love and Freedom

As Thomas Oord has explored in The Uncontrolling Love of God, the very nature of God is noncoercive love that refuses to control or force human activity or response. Oord’s theology becomes problematic when God could be accused of passivity or impotence, but his point that love is by nature noncoercive helps us to understand the distinction between a God of sovereign love and a God of totalizing control. Yes, God promises to work all things out for good, and yes, God promises that history is leading toward a glorious righting of all that is wrong with the world, even as it is also leading toward healing and forgiveness and restoration for those who are wounded and sinful and lost. But the New Testament writers also underscore that the power God exerts is the power of love. Not the power of manipulation. Not the power of control.

Interwoven with this story of love is a story of powerlessness. In Jesus’s death on the cross, he is both proclaiming his love for human beings and subjecting himself to the human and cosmic forces of sin and death. This ultimate expression of love takes its shape in relinquishing control. Suffering with people, and on behalf of sinners, is a central part of the story of the life of God. It is in the crucifixion of the Son of God that we understand the different type of power that love wields. It is a noncoercive power, a gentle power, even a humble power. And it is precisely this power that raised Jesus from the dead.

Interwoven with this story of love is a story of powerlessness. In Jesus’s death on the cross, he is both proclaiming his love for human beings and subjecting himself to the human and cosmic forces of sin and death. This ultimate expression of love takes its shape in relinquishing control.

Again and again, the New Testament writers insist that the fledgling little Christs to whom they are writing must pattern their lives on that of Jesus. They must look to his life, his suffering and death, his resurrection, and then allow his Spirit to equip and empower them to live out that same love. God’s love is ongoing, and exists outside of his followers. God’s love is manifest in the goodness of creation, in the goodness of God’s miraculous healing work, and in the new creation that was initiated by raising Jesus from the dead. But God also insists on expressing the power of love in and through human beings.

In the middle of the book of Ephesians, the writer breaks into an ecstatic prayer of wonder over the expansive nature of God’s love. Then he concludes with praise for a God who is “able to do abundantly far more than all you ask or imagine” (Ephesians 3:20). It is easy to read and pray those words as if God is a force ready to overpower human will, ready to exert unparalleled control over history or nature. But the prayer goes on to say, “according to the power [of love] that is at work within us.” God’s “abundantly far more” happens in and through God’s people, in and through the body of Christ enacting the love of Christ within the world.

This active participation in the love of God takes a multitude of shapes and forms. We participate in love when we receive God’s love, through prayer, through the Eucharist, through acts of kindness and faithfulness offered to us by others. This active participation also happens as we surrender ourselves to God’s love and give it in kind, as we follow Jesus’s way of healing and feeding and showing compassion, as we affirm the dignity and inestimable worth of the poor and marginalized, as we confront injustice, and as we give generously and freely, expecting nothing in return.

This active participation also happens as we surrender ourselves to God’s love and give it in kind, as we follow Jesus’s way of healing and feeding and showing compassion, as we affirm the dignity and inestimable worth of the poor and marginalized, as we confront injustice, and as we give generously and freely, expecting nothing in return.

As we approach election day, as we wonder whether God is paying attention, as we ask how God can work our national situation for good when every day brings reminders of lives lost and threats of violence and division—we do not need to resolve these doubts with a sense of fatalism. The comfort Christians can find in the truth of God’s love is not from a sense of inevitability, but rather in accepting the invitation to participate in that love no matter what happens. No matter which party gains or loses power. No matter what justices sit on the courts. And no matter what suffering comes into any of our lives as a result of this political juncture.

For at least the past five hundred years, Western countries have increasingly relied on a particular understanding of control to solve human problems. By controlling data and increasing our reliance on science to understand both biological and social ills, we have made advances that allow us to create vaccines against disease, predict the spread of illness and the outcome of elections, and protect human beings from harm. But scientific control is unable to eradicate human suffering. A God who is understood and offered primarily as a God of control will mimic the secular gods. A God who can both enter into human suffering and who can redeem and transform that suffering is a different kind of God. In this moment, believers from across the political spectrum are invited to follow this God of love, with our minds, soul, strength, and will.