Part I of this piece appeared in Breaking Ground last week.

The Deep State

It’s safe to say that Graham County is Trump country. At least it was in 2016, when Donald Trump won 80 percent of Graham County’s vote. No other county in North Carolina gave him a larger percentage. There are many reasons for this, but one of them is the county’s wariness toward the federal government. For Graham County residents, the federal government isn’t only in Washington, DC; it’s also in their back yard.

About 74 percent of the county is owned by the federal government—specifically the Forest Service—including two-thirds occupied by the 531,148-acre Nantahala National Forest. “From the federal perspective, honestly, the big issue is always our national forests and how we interact with the Forest Service,” Garland said. Part of the problem is the conflict between Graham County residents and the Forest Service on the issue of logging. Garland said the Forest Service is concerned that logging will be done in an unsustainable way that will decimate Graham County’s natural beauty. “We try to keep a really good, positive relationships with our local forest personnel. But the big issue is the federal government not allowing us to have access to the lands to log the lands, and there’s a level of distrust there, and to a degree it goes both ways.”

Graham County residents see the federal government hoarding productive lands to preserve as wilderness, limiting the economic freedom of locals. “The people have been pushed around by the government for years. They don’t trust the government,” Farley said. The federal government “systematically took a lot of land sixty or seventy years ago. The Forest Service started it with the lakes and basically came in and took a lot of prime land for the construction of the lakes and then they built the park.”

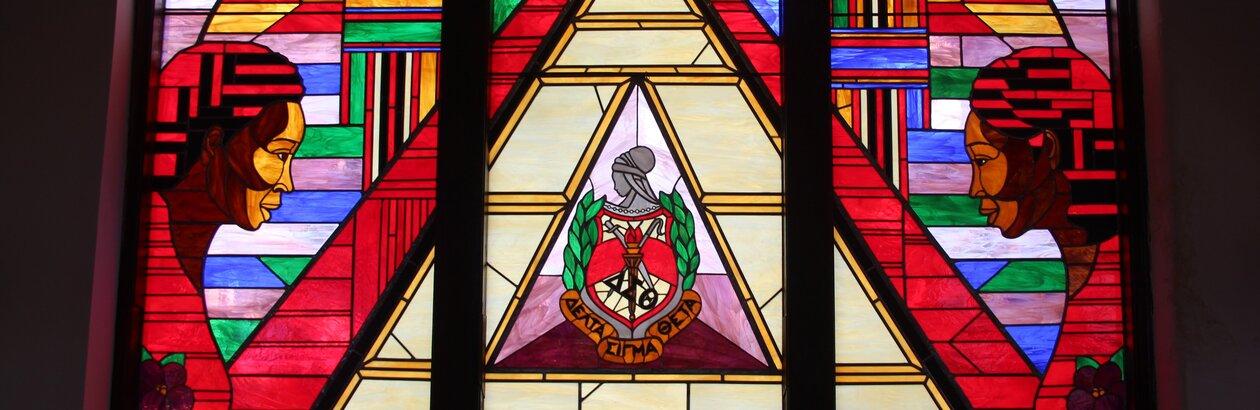

Photo by Andrew Wainer

As with intergenerational trauma from alcoholism, Graham County residents also have long memories when it comes to federal-government interference. “The people here have been here for generations; they have faced a lot of interference in their lives from the federal government,” Colwell said. “Back in the thirties the Tennessee Valley Authority came and took land away from people for dams, for Fontana Dam and other dams in the area. The government took over properties for the national parks. The people here were farmers and lived off the land and relied on hunting and fishing, and they still do, they still hunt and fish, everybody here. And yet they’re kind of kept off [the land]; the prior three or four generations are kept off the property they had lived on. They are kept off and have to comply with the government regulation. There’s some resentment.”

Colwell, who is from upstate New York, and is a relatively new resident of Graham County, said this proximity to heavy-handed federal power and authority shaped the local mentality. “People here are tough, they’ve been here for generations, they’ve been taken advantage of quite a bit,” he said. “A lot of people have a chip on their shoulder. A lot of people don’t want change. . . . They feel like, ‘We didn’t ask you to come help . . . so just leave us alone.’”

“People here are tough, they’ve been here for generations, they’ve been taken advantage of quite a bit.”

Garland agreed that this history generates an intuitive distrust of the feds. “People in this county . . . really feel let down by the government. So when a federal official comes in and makes all these promises, we’re like, ‘yeah right, more of the same,’” she said. “We’re not gonna take it to the bank because . . . the federal government hasn’t lived up to its promises for almost the last 150 years, so why should we concern ourselves with that?”

Benign Neglect?

Residents said they expect roughly the same level of support for Donald Trump in 2020 as in 2016. No one expects Joe Biden to put Graham County in his column in what will be a hard-fought contest for North Carolina’s fifteen swing-state electoral votes.

But while Trump can consider Graham County a sure bet, this isn’t a place where he boasts fanatical support. You won’t see many Trump signs here. In great part due to the history discussed above, many here see Washington, DC, and national-level politics—no matter who is president—as more or less irrelevant to their lives, local land issues aside. Many people in Graham County said that—for the most part—the Trump administration hasn’t affected them one way or the other.

Nationally, if about half of Republicans think God voted for Donald Trump in 2016 and 28 percent of Americans believe Trump is “working for the devil,” Graham County’s response to Trump is more a shrug of the shoulders. “I can’t see any real change [from the Trump administration],” said Garland. “Trump brought in the Opportunity Zones, [but] no one has been able to implement one in western North Carolina that I’m aware of. . . . There’re so many strings to it. It’s almost like . . . back when Obama did the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, there were so many strings with that nobody could hardly implement it either.”

Paulos also saw only marginal changes from the Trump administration, crediting the nationwide pre-COVID-19 economic boom under Trump with contributing to a business upswing in Graham County for firms with work outside of the county. “Three fairly large construction firms that are based in Graham County [where] most of their workers travel, they will be working on a highway in Florida or Virginia or Georgia, or wherever, and their business has absolutely gone up. Construction business in general has gone up. They have absolutely seen the benefits from that.” Paulos also said that the administration has been supportive of local workforce training for people suffering from substance abuse—the Recovery-to-Work project noted above.

Garland also noted that the county has benefitted from the overall national economic boom under the Trump administration, at least before the COVID-19 pandemic. “We’re building more houses than we’ve ever built . . . and our construction companies,” she said, “they stayed really busy, but most of the project are outside Graham County.”

So the overall robust national economy over the past several years trickled down to Graham County and made an impact. But Paulos, Garland, and other county officials credit local and state action more than the Trump administration with bolstering the local economy. The lack of major impact from the Trump administration in Graham County is even more surprising given that the White House chief of staff is none other than former North Carolina Eleventh Congressional District representative Mark Meadows. Meadows served Graham County and the rest of the Eleventh District as its congressional representative from 2013 until early 2020, when he resigned to work in the White House. The Congressional seat is currently vacant.

Photo by Andrew Wainer

When asked why more people didn’t discuss Meadows’s impact on Graham County, Garland said, “Probably nobody mentioned him because we haven’t felt any impact. The only time you see the federal representation in this county is during an election year. Sometimes you don’t even see the federal election representation in the county during an election year.” Wiggins, a lifelong Republican, also said, “I believe Mr. Meadows got caught up in the Washington environment. Then he got involved with the Freedom Caucus. I think he lost his focus, and I think he forgot about the Eleventh District.”

Apparently many voters in western North Carolina feel as if Meadows abandoned them because in June his handpicked successor, Lynda Bennett (also endorsed by President Trump), was crushed by twenty-four-year-old newcomer Madison Cawthorn in the June Republican runoff election.

Religious leaders in Graham County also see Trump as marginal at best to what happens in their congregants’ lives. “Just to be honest with you, I don’t think that these problems would be any better or any worse, regardless of who the president was,” said Shiplett. “A lot of our issues here . . . are more state government issues. Our situation is very unique and it would take a long time for the benefits of those kind of things [federal-level policymaking] to trickle down to us.”

“Just to be honest with you, I don’t think that these problems would be any better or any worse, regardless of who the president was.”

Think Globally, Act Locally

In spite of its wariness, Graham County is not disconnected from the federal government. In addition to the massive amount of federal land in the county, it also depends on federal support for programs such as Recovery-to-Work. But what it does seem somewhat aloof from—in spite of monumental levels of rancor and passion nationally—is national-level politics.

For Graham County residents and officials, what counts for making their lives better or worse is what’s done locally in Robbinsville and at the state level in Raleigh. And in spite of the county’s myriad challenges and internal debates, officials said local politics generally seem to work. Party politics isn’t a religion here—residents said political leaders often do what’s best for the community regardless of party orthodoxy. “Even though Graham County on paper is super Republican and their values are very conservative, they do know how to assess what’s best for their people,” said Paulos. “If something is likely to be beneficial for their people, they are likely to support it, regardless of what party it’s coming from.”

Photo by Andrew Wainer

The Graham County Commission is overwhelmingly Republican, but that doesn’t predetermine their policy preferences. And the alcohol issue aside, Paulos said, “We’re seeing people working together to figure out what we need,” asking, “What’s wrong and how do we fix it?”

One nationally relevant example is Medicaid expansion, which the Republican Graham County commissioners backed unanimously. “[Graham County] Commissioner Wiggins has led that charge,” Garland said. “He became quite known in the state of North Carolina for his advocacy for it, which was really interesting because he’s a lifelong Republican and really went against the party line. . . . That’s a state decision that’s really important for the people in Graham County.” Graham County is one of a number of state and local authorities nationwide that are rebelling against the Trump administration and Congressional Republicans in supporting Obamacare by seeking its expansion.

“We have a very high uninsured population, we have a lot of poor working people, and that is something that, to us, is going to make a huge difference in the quality of life and their ability to sustain employment and their ability to sustain a living, [more of a difference] than an Enterprise Zone or an Opportunity Zone,” Garland said, contrasting it to other Trump administration programs.

For his part, Wiggins said his support of Medicaid expansion is common sense. “In North Carolina alone we have 500,000 people without health insurance . . . and those are primarily people that are employed, working every day—carpenters, construction workers, people working in restaurants.” Channeling Senator Bernie Sanders, he added, “In today’s society, health care is a necessity, it’s not a luxury.”

“In North Carolina alone we have 500,000 people without health insurance . . . and those are primarily people that are employed, working every day—carpenters, construction workers, people working in restaurants.”

County officials rarely mention Meadows, who one would think could pull lots of White House strings. But they often mentioned their state representative Kevin Corbin—also a Republican—who in 2019 co-sponsored North Carolina House Bill 655 to expand Medicaid. The bill is still pending in the North Carolina legislature. “He’s been incredibly supportive. It’s been great to have this bipartisan-level support,” Paulos said. “Graham County isn’t used to getting that kind of attention.”

Garland also praises Corbin and reaffirms the importance of state-level policymaking for the county. “Most of our interaction is with the state government. We have a really good relationship with our representative,” she said. “He listens, he actually shows up when it’s not an election year, he calls us, he checks in with us. . . . If we need to see him, he’s over here. He’s been a really good advocate for Graham County.”

“He listens, he actually shows up when it’s not an election year, he calls us, he checks in with us. . . . If we need to see him, he’s over here . He’s been a really good advocate for Graham County.”

Garland calls herself a “policy wonk” and said she works at the local level in her native land because she felt compelled to do so. She emphasizes the grind-it-out practicality of local- and state-level policymaking. “I think there are a lot of great ideas that come forth, but it’s like anything with policy, the devil is in the details,” she said. “The implementation of policy is a whole lot harder than framing policy.”

Hope

The summer of 2020 was less tumultuous for Graham County than the rest of the county. Given its remoteness, as of July 2020, the coronavirus barely has registered in the county, and tourists continue to visit from the Southeast and beyond. There are no protests on the streets of Robbinsville.

But as America’s self-esteem sinks to the lowest level in twenty years, Graham County—in spite of its particularity—provides an example of a trend taking hold throughout the country. Prior to the coronavirus, the local leadership team was making slow progress digging the county out of its economic depression—unemployment was down, homeownership was up. Local leadership was making a difference.

Even in essentially what is a one-party county, local issues were tackled with practicality, occasional bipartisanship, and a focus on how to make community members’ lives better. As Congress fails to address a pressing national problem that almost everyone believes needs action, even staunch conservatives are responding to policy issues through a local, cooperative, and communal rather than national partisan-political lens.

Photo by Andrew Wainer

With seemingly intractable national-level division, perhaps the next decade—as we dig our way out of the economic rubble in the wake of COVID-19, out of the political rubble of hyper-partisanship, and out of the cultural rubble of failure of trust in institutions—will be about community-level rebirth and action. Just as Graham County citizens count more on local and state officials to make their lives better, solutions to police brutality and reform will largely be determined by city councils and states across the county. Large majorities—71 percent—of Americans are angry with the state of the nation. National reform matters, but Americans are increasingly focused locally, away from a robotically repetitive and hollow national political discourse.

Perhaps the next decade—as we dig our way out of the economic rubble in the wake of COVID-19, out of the political rubble of hyper-partisanship, and out of the cultural rubble of failure of trust in institutions—will be about community-level rebirth and action.

A recent survey found that Americans are more than twice as proud of how their community handled the coronavirus and protests over police brutality than they are of the national-level response. “Local communities provide a beacon of kindness and competence for Americans across the nation,” a summary of the survey findings said.

Being able to listen, debate, compromise, and create starts person to person in neighborhoods, towns, cities, and suburbs. The problems that ail Graham County ail the country. “I think that’s how the system is supposed to work: ‘Tell me how I can make this better where you agree to work with me on it,’” Commissioner Wiggins said. “That’s gone. I don’t know when we lost that, but it hasn’t been in Washington in a long time. I think that hurts everybody. . . . Your government is not working for you anymore, they’re working for this party ideology.”

Community, pride of place, neighborliness, solidarity: these are built from the ground up. “I don’t think there’s any one magic bullet that’s going to help Graham County,” Garland said. But one thing is certainly needed: for people to “really truly see a reason for hope. If you lose your hope, you’re not able to see what a future could look like.”

And in the end, local solutions—multiplied by thousands—can become national solutions—if they are allowed to trickle up. It might be that the healing that will come will begin quietly, unspectacularly, when more people refuse to give up and move on even when that’s the reasonable thing to do; even in places the world doesn’t know exist: places like the hollows of these mountains.