My parenting group, to say the least, wasn’t buying it. How can you actually raise Jewish children without the anchoring spaces and events of a synagogue? And how could Rabbi Hirsch—credited as the founding figure of modern Orthodox Judaism—have even imagined it? As the father of an infant, I was already the outlier: everyone else’s children were old enough to be in school, already used to socializing with other Jewish kids their age on Shabbat mornings, now in need of supervision at home from parents also expected to keep working full-time.

Hirsch’s words, I found, offered a way to express what I’d already begun to feel in the first few weeks of the coronavirus lockdown, as the paragraph above circulated through Jewish institutions and we, in hard-hit southeast Michigan, watched the case numbers tick steadily upward.

Without a synagogue, I found myself falling into a different, more daily rhythm of Jewish practice, one still anchored by Shabbat but grounded in more broadly repeated actions: laying tefillin in the morning; counting the fifty days of the omer, the period between Passover and Shavuot, each night; taking five minutes in the afternoon for virtual text-study with the rabbi. The routines of Jewish life changed but didn’t disappear. Centered exclusively on my home, they’re what Hirsch called for.

The detailed rules of traditional Jewish observance—its many prescriptions and proscriptions—account for a large part of this. So too does the perspective learned from Judaism’s history of creative response to exile from the places and practices with which Jews have grown familiar.

I’m aware that what I’m about to describe doesn’t have perfect analogues in Christian life—and I’m not presumptuous enough to suggest what useful ones might be. But this coronatide is a period of exile: from churches and synagogues, from schools and clubs, from workplaces, from friends and family. For all of us, life in our own homes begins to feel like something of a miniature diaspora. These are conditions and feelings with which Judaism has grappled for millennia.

***

As stark as this season’s realities may be, they’re not as drastic as the change that was Hirsch’s starting point. His call for a Judaism without synagogues comes in an essay discussing the month of Av, the late-summer portion of the Jewish calendar marked by the destruction of the First and Second Temples. The month’s ninth day—Tisha B’Av—is one of fasting and lamentation. The week preceding it, for traditional Jews, resembles the period of shiva, mourning for a close relative. Tisha B’Av marks a radical break in Jewish history: from pilgrimage and sacrifice to prayer and study; from a central, national house of worship to local centers, often in competition. To talk about Av is to talk about the period in which Jews were cast out of all that was familiar about Jewish worship.

Yet Hirsch suggests voluntarily reenacting this break on a smaller scale. Sudden decentralization, he holds, is what the Jews of nineteenth-century Germany need. In part, this is Hirsch’s response to the early Reform movement, which he believed outsourced religion from the home to the synagogue, effectively limiting Judaism to one day a week. And he feared something similar was beginning, despite continued surface-level observance, in Orthodox Jewish families as well. The places and times of Jewish life were becoming too clearly distinguished.

Jewish observance consists largely of making such distinctions: between pure and impure, kosher or treyf, Shabbat and the workweek. The Hebrew word kadesh, to sanctify, means more literally to separate or set aside. Shabbat in particular is made holy by being set apart and distinguished from other days; in the closing havdalah ceremony on Saturday nights, Jews bless God for allowing us to make this distinction and for separating the sacred (Shabbat) from the mundane (the rest of the week).

But there’s a danger in this to which Hirsch was attuned. A century later, Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, one of the leading figures of American Orthodox Judaism, would frame it as the distinction between “religious man” and “Halakhic man,” referring to the difference between one who follows a religious sensibility and one whose life is ordered according to the strictures of Jewish law. He has no time for the religious outlook in which “the temple stands at the heart of religion.” Synagogues and religious schools are “minor sanctuaries,” but the “true sanctuary is the sphere of our daily, mundane activities.”

Both Hirsch and Soloveitchik discuss (through different vocabularies) a defining feature of modernity’s secular age, what Charles Taylor refers to as the “immanent frame”: a way of perceiving the world that values the natural and material over the transcendent and supernatural. Too much focus on the synagogue, too much emphasis on observing a single, time-bound aspect of Judaism—and the six days of the regular week aren’t merely “mundane,” but secular; God and transcendence not sanctified in the Sabbath but circumscribed within it.

W.H. Auden put the dilemma more conversationally in the closing section of his 1942 Christmas oratorio, For the Time Being. As the pageant ends, its narrator returns readers to the period of mundane time: life between the crucifixion and the resurrection, when “The happy morning is over, / The night of agony still to come; the time is noon.” This “Time Being,” he writes, “is the most trying time of all,” a period defined by “bills to be paid, machines to keep in repair, / Irregular verbs to learn, the Time Being to redeem / From insignificance.”

Halakhic man, not bound to the place of worship or focused on achieving transcendence, has something to teach us—Jews and Christians alike—about how to deepen and sustain faith in our own virus-driven exiles from church and temple.

***

The exile we’ve been living in since March is more extreme than Hirsch’s thought experiment. Precisely those pillars of community that he would let stand in place of the synagogue are also closed off: schools and study groups, welcoming guests to share meals, many forms of charitable work in the community—beyond the nuclear family, everything embodied has been proscribed. It’s not just that we can’t go to synagogue or church and must now spread out the behavior that defines that day across the full week. Even as the workweek starts to blur into a weird sabbatarian pause from what once was normal, we’re cut off from the actions that once defined the Sabbath itself.

It all feels like the opposite of kadesh: Shabbat and holidays set aside, out of reach; while the weekday work is to infuse the most mundane, repeated, and niggling tasks into habits infused with religious meaning.

In Jewish communities, this is particularly jarring. The need to pray in community is common to Jews, Christians, and others, of course—but Jewish tradition makes it quite clear that private prayer should be avoided. Without a minyan, a prayer quorum of ten, central portions of the liturgy can’t be recited. In a time of mourning, it’s especially difficult and poignant that this applies to the Kaddish, which most Jews have been unable to recite for family members lost years ago and those lost more recently.

But the English word prayer obscures a distinction between two different kinds of Jewish speech-acts: avodah (or service) and bracha (or blessing). Avodah defines communal prayer; brachot, though integral to avodah, are not limited to it. Certain blessings require a community—sometimes three, sometimes ten—but most are meant for the individual.

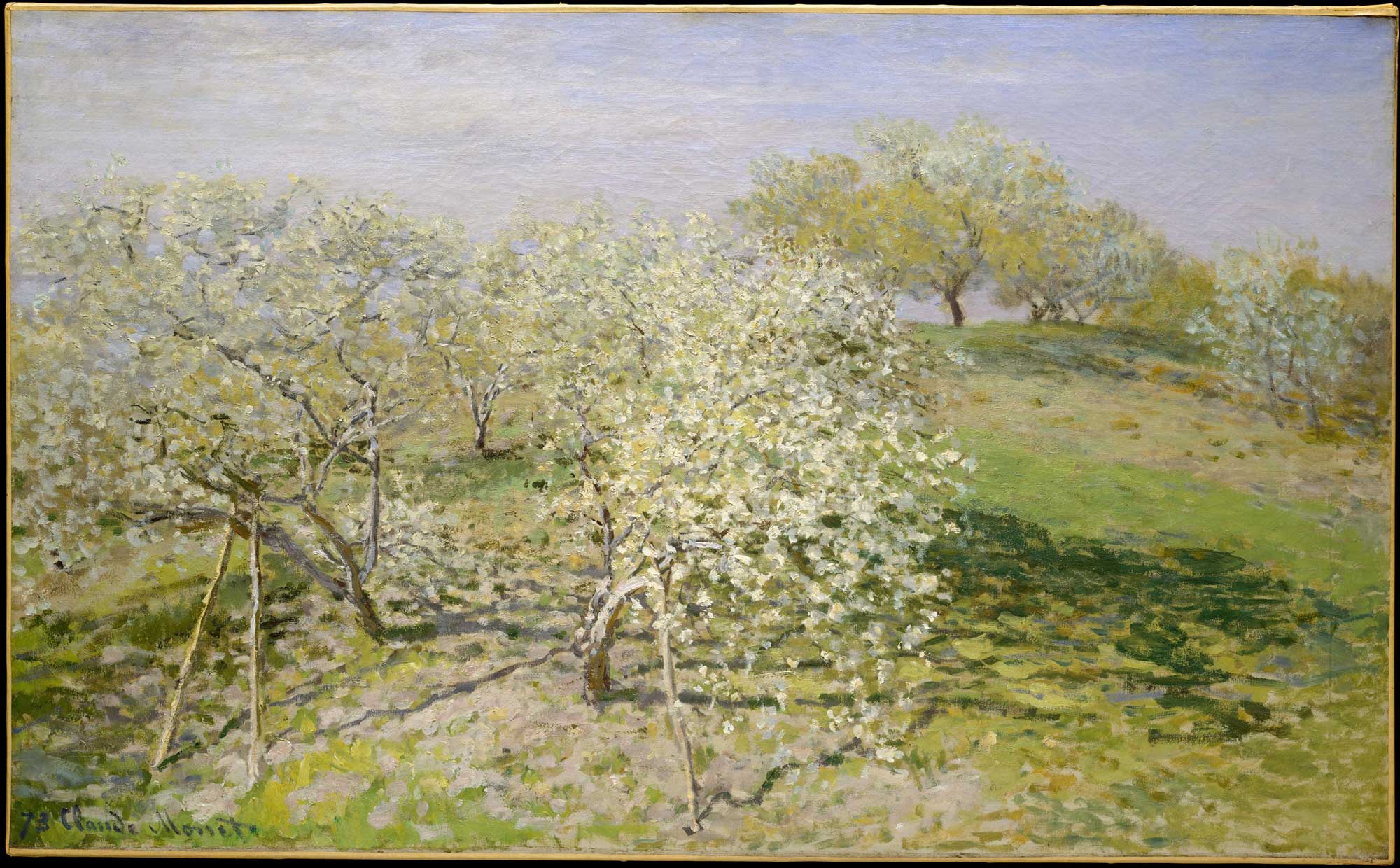

Moreover, many brachot are said over actions that have no inherent religious quality—for deeds that seem at home in Taylor’s immanent frame: blessings on wearing new clothes; on washing hands; on urinating; on smelling fruit, flowers, trees, or anything fragrant; on seeing lightning; on hearing thunder; on seeing the ocean; on seeing the trees budding at winter’s end; on seeing a secular academic, the president, or the Queen of England; on encountering a rare animal; on hearing good news—and the news of a death.

Brachot demand intentionality, the awareness that one does something not necessarily because one is a Jew, but as a Jew, with the knowledge that there is transcendence which may not be visible but exists nonetheless. The talmudic tractate Berakhot, which discusses prayer and blessings, is included in the section devoted to Zera’im, or seeds, otherwise devoted to agricultural laws. Among the many explanations offered for this quirk of organization is the idea that brachot are the seeds of Jewish life: a way to grasp and sanctify mundane acts by setting them, at least momentarily, outside their immanent frame.

The difference between the sacred and the mundane, on this account, lies in the form of attention we grant everyday acts; Judaism’s web of laws creates opportunities to do this. Even in my frantic, nervous rush through the grocery store, I have to pause, from time to time, to check to make sure what I’m buying is actually kosher: a small moment, yes, but a Jewish one, and one that carries over to the kitchen as I cook, and to the table as we eat. When I pass from room to room in my home, I see the mezuzot on the doorposts; when I go outdoors, I know that my clothing, the knit yarmulke I’ve finally taken to wearing regularly, will mark everything I say or do as something done by and as a Jew.

***

And then there’s simply walking.

Almost every Jewish community has a “Shabbos park”—a public, outdoor space where families gather on Saturday afternoons, after shul and lunch and possibly a nap, to let the kids play together and the parents socialize (or nap). What I didn’t realize, until my daily lockdown constitutionals took me past our park midweek, was how clearly this space is mapped into my mind as the Shabbos park: each visit, now, recalls the spirit of that day. Somehow, just going there is in itself a Jewish act.

This isn’t something I could have deliberately created—certainly not in the days after the rushed week of email conversations and synagogue updates that restricted and eventually canceled our community indefinitely. It was built, through slow accretion, by years of habit: all those Saturdays I’ve spent walking to the Shabbos park, walking through the neighborhoods around it, walking to the houses of community members for meals, for a drink, to play board games, to sit and talk. And walking, of course, to synagogue.

The physical constraints of Shabbat observance mark the day as holy—but also provide the most condensed example of how Halakhic man transforms the mundane while making a home in it. There’s no inherent difference between Saturday and the rest of the week. All that changes is behavior in my control: that I can’t drive or ride in a car, turn on the lights, cook, walk outside the boundaries of the eruv (the area in Jewish neighborhoods that symbolically extends the private domain of the household into public areas, allowing activities forbidden in public on the Sabbath); the time I have to read with my wife or play with my daughter without glancing at the clock. All these have marked my Saturdays as Sabbaths; and a decade of walking similar routes to and from this synagogue has marked the spaces I pass through as somehow Jewish.

That my mental map of the city has been formed around walking to shul isn’t enough to sustain religious practice, of course: it provides just enough of an echo to remind the families still gathered, six to ten feet apart, in the Shabbos park, that by being in this park we’re still marking Shabbat, remembering it and guarding it. But it does highlight the ability of repeated action to mark the mundane as religious—or, more rightly, to highlight and draw out the sacred from within the mundane.

It does highlight the ability of repeated action to mark the mundane as religious—or, more rightly, to highlight and draw out the sacred from within the mundane.

This, ultimately, is the goal of the myriad laws and regulations that define traditional Jewish life: not to control or constrain the individual, but to mark each action as, in some way, defined by recognition of God’s truth: “Halakhic man,” Soloveitchik writes, “apprehends transcendence. However, instead of rising up to it, he tries to bring it down to him. Rather than raising the lower realms to the higher world, halakhic man brings down the higher realms to the lower world.”

And I suspect it’s also true of the many small habits of Christian life and prayer, those items of mundane life and overlooked charity that are easy to ignore—or let slide with the promise that you’ll make sure to perform the public, communal deeds from which we’ve been exiled. “Halakhic man” might be a Jewish concept but has his Christian counterparts as well. What Hirsch sought and Soloveitchik described is more than a set of behaviors—but a particular way of paying attention to the world and oneself, produced and sustained by habitual repetition, that transforms the mundane without seeking to escape it.

***

One day, of course, all this will be over: we’ll go back to our churches and synagogues and sing without fear of spreading a virus. But I know from the rhythms of synagogue attendance on a university campus that the feeling won’t last: renewed commitments, fueled by the quest to see old friends, almost always fade.

What we’ll face then as Jews and Christians, as communities of religious believers, will only be a seemingly less urgent version of the task we already face with houses of worship closed. Auden, of course, describes it well: “Back in the moderate Aristotelian city / Of darning and the Eight-Fifteen,” we’ll look around and mutter aloud, “It seems to have shrunk during the holidays. The streets / Are much narrower than we remembered; we had forgotten / The office was as depressing as this.”

“Holiness is created by man, by flesh and blood,” Soloveitchik writes; the time being is redeemed through routine, through practice, through ritual. In a small way, we’re all now sharing in the bewilderment of Jews from the first century suddenly without the Temple, forced not merely to adapt but to develop and embrace ways of sacralizing that already existed. For them, it was study, prayer, a reimagining of the Sabbath table set with candles, challah, and wine as a home-bound version of the Temple itself.

For us, it can be something less drastic but no less essential: taking on the mindset of the Halakhic man, developing the habits and routines of a Jewish or Christian home, understanding prayer not merely as service, worship, or request, but as blessing—the incorporation of ways to break through the immanent frame into our daily lives. Not just to notice the cracks where transcendence breaks through, but to make them ourselves.