1/6

On January sixth, I was working in my office at the station in downtown Marion, Virginia, on some long-term legislative issues we expect to confront at the next session here in the Commonwealth, when I received a text from a friend: “The Capitol has been overrun.” I turned on the news in my office just in time to see something I’d never imagined—the House Chamber door barricaded with furniture, several plainclothes agents with their service weapons drawn, anticipating a breach.

I think what I said was, “Holy shit.”

After being honorably discharged from the US Army as a military police officer, and before entering service as a municipal police officer, I’d worked a few years as a physical security contractor for the Department of Justice Protective Service and the Department of State Bureau of Diplomatic Security. Although those missions were certainly quite different from the security mission at the Capitol, I know enough to know that this was bad. Really bad. As the news began to spread around the DC-area law-enforcement community that I’m a part of, the commentary quickly shifted from “Wow. . . this protest went a bit too far” to “They better get this under control before someone gets shot.”

Then it happened. A protestor—should we call her an insurgent? a patriot? what is it that was going on? what did she think she was doing, and what was she actually doing?—who was attempting to breach a door was shot with a single well-placed round and died almost immediately. I know many of those there said that nothing would stop them from preventing what they saw as an election theft in process, but I can’t imagine they had any intention of confronting a 115-grain jacketed hollow-point. I know that the Capitol police officer who shot her never dreamed of having to confront what he confronted that day.

That was when I called my wife and told her to turn on the news, to make sure our four children were watching what I am convinced was the most significant political event of their lifetimes so far. Everything will be different from this point forward. It had finally happened.

But what was it that had happened?

The Political Flat Earth

Up until this year I was pretty active on Facebook, and enjoyed keeping up with old friends and making new acquaintances online. Then, after the murder of George Floyd, and the riots that followed, there was what seemed like a sudden shift in the conservative and loosely Reformed Christian circles I was in. Police, in those circles, had tended to be seen as the “good guys.” But this summer and fall, without any buildup, some of my closest ideological allies started talking about how they wanted to purchase guns to protect themselves from the police. It was as if their entire view of the world had suddenly changed, and now it was the police who were their personal enemies. These interactions alone caused me concern: What was it that they thought was going to happen? But what really worried me was the sudden eschatological tone of much of the political discussion among Christians, even those Christians who typically weren’t prone to reading such things as signs of the times. It wasn’t just the Pentecostals: politically inflected millenarianism was affecting people across denominations and traditions.

Over the next few months I saw many people I knew well become what I can only describe as political flat-earthers, falling deeper and deeper into thinly evidenced conspiracies about everything from the pandemic to the election. In response, a rock-solid “official narrative” grew up about how normal people should regard these things. “No,” said the talking heads on MSNBC, “there was no election fraud at all, and also BLM protests are not super-spreader events while anti-lockdown protests are. No, there is no hypocrisy to see here.” There was no room to question that narrative without being labeled a conspiracy theorist and a right-wing extremist. In what seemed to be a kind of reaction, some of those who did question it seemed to step outside the realm of normal debate altogether, entering into some kind of widespread psychosis amounting to a literal break with reality. And the fact of the bizarre beliefs and behavior of some on the right allowed some on the left to be confirmed in their regard of all of those on the right as contemptible, dangerous, and insane.

I don’t understand fully what has happened. But one thing that is clear is that the power of social media to shape reality is part of that picture: in the attack on the Capitol, the memes materialized. Written words and images unleashed a universe of tactile forms. All of the rhetoric had finally found its final form. Blood.

Summer of Fire

The summer had prepared us for this. Whatever one thinks about the both-sidesing of some post–January 6 rhetoric, from a law enforcement professional’s perspective, what is happening is related in its sheer material reality: mobs on the left, and then on the right, have, over the past ten months or so, made political violence normal in the United States.

Just as we saw the violence at the Capitol, and in response prepared for potential further violence on January 20—violence that, thank God, did not materialize, in part because of our preparations—over the summer we saw the riots and destruction spread from city to city across the country, and prepared, uneasily, for potential violence in our own town.

Over the summer, we had two protest events: one small, one regionally large. In these events, we saw people motivated by the entire spectrum of expression, from average citizens on both sides of the political aisle merely concerned with exercising their rights of freedom of speech and assembly, to advocates for anarchism and of white supremacy. We literally had it all. During the first event, a fiery exchange of words occurred at the site of a Confederate war memorial on the courthouse grounds. That was followed up by a cross burning in the local BLM organizer’s yard. Suddenly our event went from somewhat run of the mill to making national and even international news. The vitriolic local exchanges, both in person and online, went up in intensity accordingly. And of course everyone who was planning to protest, and counterprotest, locally had been watching the way protests were going elsewhere in the country: watching their own media, with their own stories about who the bad guys were and who the good guys were in each protest, and preparing themselves with their own scripts of action and rhetoric.

This intensity resulted in the largest law enforcement deployment in southwest Virginia history, with over two hundred police officers in Marion (population five thousand) on the day of the second event. Even with so many officers on the ground, we still were at a significant disadvantage with five hundred to a thousand protestors and counterprotesters, just about evenly split, packed into an area less than an eighth of a mile square, all ultimately converging on a three-block radius in downtown Marion. In preparation for what we knew would be head-on collision, we developed a system of barricades and “gates” that I informally thought of as “the Thermopylae Plan”—we used tall buildings and narrow streets to create more manageable geography, making several contingency plans if the situation got out of hand.

Bear in mind, participants on both sides of the debate were heavily armed, open carrying rifles. This is, after all, Virginia: it’s all completely legal. And my officers were in the middle. The most intense moment was at the conclusion of the march, when both groups met, separated by barricades about thirty feet apart, at the main intersection in town. A twenty-minute verbal exchange ensued. I hear myself describing it like that, with the police officer’s passive voice: let me try again. People in the crowds were talking to each other. They were screaming at each other. Slogans, chants, accusations. Also ideas, jokes, heated conversations. It seemed to be on the edge of catastrophe. I spent half my time encouraging my guys on the radio to assess properly what they were dealing with: yes, that BLM protestor has a gun, but look, it doesn’t have a magazine in it, he’s not a threat. Yes, that counterprotester is getting in your face: let him. I allowed it to go on, because I was convinced that it needed to happen.

Politics is a public conversation. And this was freedom of assembly, freedom of speech. For better or worse those words needed to be exchanged, and as a police officer it’s my job to protect those rights, and physically protect those exercising them, to enable them to continue to do so. In the end, there were no arrests, no injuries, and no incidents of property damage.

For better or worse, words needed to be exchanged, and as a police officer it’s my job to protect those rights, and physically protect those exercising them, to enable them to continue to do so.

I didn’t just try to protect those conversations, over the summer: I had them too. During one of the summer’s conversations about defunding the police, I spoke with one protester who insisted that “we don’t need the police in our communities.”

I’m sympathetic to the ideal of community policing. But there is a core job here that I do not think is one that most community members are able to do by themselves. “How do you determine who the offender is, and what happens to him?” I asked. He did not answer.

Just the Facts

I believe this brief exchange highlights one of the most serious problems facing our nation today: a lack of confidence in processes and institutions. A whole lot of processes, and a whole lot of institutions. Let’s face it, adherents to both parties believe national elections are a sham, either through Russian interference or absentee voting—we may as well just have a revolution. Most everyone it seems feels the same way about the criminal justice system, because either it fails to dispense “true” justice—it’s part of the “deep state”—or because it’s merely an arm of oppression. This despair is not a partisan issue. It’s an infection raging in the social body of our nation, and it seems almost no one has any intellectual immunity against it.

Suddenly it seems everyone would rather simply take it outside. We saw these images in almost every city and town in America. Images of violence in exchange or action, splattered across the national news in waves not seen in decades.

A key job of the police, and one that other citizens are less well-equipped to do, is to do what people don’t have the time or temperament or training to do when they are in a mood to take it outside. That is to find out what actually happened: to investigate.

In the judicial system, we require evidence beyond a reasonable doubt—it’s not about what you know, I was told again and again, it’s about what we can prove. As a young officer I can’t count the number of times I “knew” someone had “done” the proverbial “it” but found that I was unable to prove what I thought I knew. As a more mature officer, I think about how many times I would have gone wrong if I had acted on what I “knew.” I can tell you from thousands of firsthand experiences that eyewitness testimony isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, and rumor, unless it is substantiated, is worth nothing at all: as my father would say, “Don’t believe anything you hear, and only half of what you see.”

The reason for this is simple: your brain has a habit of trying to help you out. When traumatic events occur, or when events occur at speeds you have trouble processing, your brain will help you process them by filling in gaps with predictive information or historical data. This is also why we see police officers accidentally shoot suspects who pull out cellphones, swearing they saw a weapon—because they most likely did “see” one, or at least their brain led them to that conclusion. Yet in police work we fight these phenomena with every available investigative and evidentiary tool. We know the problem exists and we strive to counteract it. This is what vigilantism lacks; it lacks it by design because the act of vigilantism is intensely personal. If your goal is to get what you want politically, your brain will give you the reasons to justify your actions. And your Twitter feed, curated to give you stories of a certain pattern, will be doing its helpful best to beef up those reasons as well.

Police training is absolutely vital to help officers develop good judgement as well as possible. Civilians have no such training, and those who are passionately committed to their political cause are not likely to be effective at sifting evidence and getting at the reality behind each incident, and each apparent pattern.

This is frustrating. Vigilantism boils down to a desire for relevance, for individual agency against injustice. The mob-violence version of vigilantism is designed to scratch the itch of making political action, political enmity and comradeship, personal in a very satisfying way. But it is not well-calculated to give justice to a community.

Objective processes, by design, have a tendency to minimize individual relevance—in many ways that’s the entire point. The problem of course is that the balm of vigilantism applied to wounded individual relevance doesn’t actually soothe anything, but rather results in a deeper alienation from the very populace it seeks approval from, creating an unending chain of violence. We have to find ways for members of the public on both sides to actually have political agency, relevance that do not come at the barrel of a gun, the invasion of a public building, or a swung crowbar. That is why a crackdown on political speech and the freedom of assembly would be counterproductive: we can’t attempt to emasculate citizens and then act surprised when, on both left and right, they lash out.

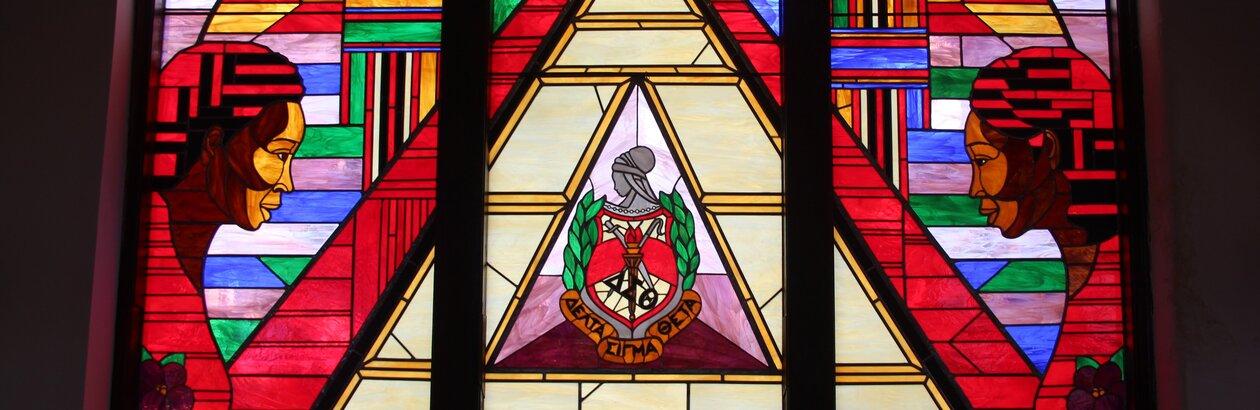

Photo by the author.

I’m the kind of law enforcement professional who continually prepares for the worst outcome, so my team does well when the reality is anything better than that, and if we do face the worst, we can at least handle it adequately. We prepared for violence on Inauguration Day that did not come. It may be that the new administration will see a general calming of the national temper. But that may not be the case. What we are doing is preparing for intense and public political discourse, with bad actors and violence sprinkled in, as we saw this summer. What we must not do is prepare to shut down that discourse. It is our job to protect it.

The Troubles

It’s natural, and helpful, to try to find analogues in current political violence to that in the past. I’ll be spending this year consuming any and all written after-action reports from critical events in an effort to identify weak points in our own command and control and event preparation. Almost by chance I had done significant study into events like the Charlottesville tragedy just before we experienced large-scale protest events in our region, and the lessons I learned from those events were invaluable to peaceful conclusions here. Our main focus will be contingency planning, threat identification, and command training in the hope we can make good initial decisions before events unfold. One obvious, but little considered, aspect of the police response to critical incidents is that law enforcement is always outnumbered. This requires us to use a lot of passive barriers, and to always make sure we use structures and geography to our advantage, all of which require intense sand table planning.

But Charlottesville is not the only parallel. I come from a police family; my father was a police officer in Sugarcreek, Ohio, and my grandfather was the first chief of police of that department at its formation in the 1970s. I remember well the atmosphere of the 1990s in regard to law enforcement. Although during that time none of us were active-duty police, I suppose we always still felt as if we had some stake in the discussions. We all watched and read about a sudden series of what seemed like enormous law enforcement missteps: first at Ruby Ridge, and then at Waco. Then came the Federal Assault Weapons Ban in response, and then—boom. A bomb went off at the FBI building in Oklahoma City.

As I think back on those events, I can’t help but feel like we are on a trajectory toward a similar outcome: A large portion of the population feels disenfranchised politically. A few troubled souls are seeking relevance. We have seen a year of law enforcement missteps that have alienated large portions of the population from across the political spectrum. The accelerants of rhetoric and violence have been pushing the velocity of events higher and higher.

I am extremely concerned that it won’t be long before the next boom: the propaganda of the deed; politics by other means.

And I am extremely concerned that law enforcement may make similar errors, as a wave of popular fear of “domestic insurgents” encourages harsh crackdowns.

A major difference this time is that radicals on both sides seem to regard themselves as at war with their enemies, as oppressed minorities for whom violence is a legitimate choice. One could look at Germany in the 1930s or Kansas in 1861, but in my opinion the most accurate parallel is Northern Ireland, during the Troubles of the 1970s and 1980s. As in that case, both “sides” are nongovernmental actors, and police have an ambiguous relationship to them; a sense of political grievance and injustice has sparked off what seems to be a potential spiral of political violence. The Belfast-esque Christmas Day car bomb in downtown Nashville only confirmed what I had begun to see.

If this is what we are facing, then it seems to me that we must learn our lessons from the missteps not just of the FBI in Waco and in Ruby Ridge but also from those of the police in Northern Ireland. What we must do is police in such a way as to protect the public realm, not to shut it down to any one group, and in that way cut short our transformation into a society of vigilantes.

Rough Justice

What’s wrong with political vigilante justice? At the very basic level, it is not justice, because the vigilante is by his nature passionately and partisanly engaged in the political issue at hand. The ideal that we absolutely must fight to make a reality is that of a police force that acts for the true common good, apart from personal and political influence. This is not easy: it is the reason for the professionalization of policing in the first place.

D.H. Lawrence told us that “the essential American soul is hard, stoic, isolate, and a killer.” I don’t know of a nation on earth that doesn’t have some literary advocate who ascribes to it a unique strain of truculence. Yet the mystique of vigilante violence does seem to captivate the most in the American context. After all, isn’t that How the West Was Won? Imagine the scene. A hardscrabble family winding its way through the Ohio Territory confronts a murderous and bushwhacking band of thieves. The resolution comes through frontier justice, delivered by a man willing to take on the burden of sovereignty where there is no state—all aided by the majesty of Technicolor.

If no one has told you up to this point, let me be the first: The realities of the frontier were far less captivating. Fast-draw rigs didn’t exist in the Old West, most gunfighters were shot in the back, virtue went unrewarded, and more importantly—justice wasn’t always done.

The same goes for justice generally, vengeance always, and violence particularly. It’s not as magical as it seems. In my twenty years of law enforcement service, I have fired my service weapon only once, and that time only after having been on the receiving end of gunfire. It was neither beautiful nor glorious, neither adventurous nor particularly fulfilling, neither heroic nor noteworthy. I responded to a call for a domestic situation that turned violent, and when I arrived I found the suspect fleeing in a vehicle and along with other officers confronted the suspect. He exited his vehicle, leveled a Sig Sauer 9mm in my direction, and pulled the trigger. I saw the muzzle flash, and had one thought—my youngest daughter, Gwendolyn, would never know me. In the end, we all lived because we all missed (the suspect included), we didn’t feel particularly brave, and after countless hours of forensic and investigative work, along with days of courtroom testimony, the suspect was convicted in a court of law of four counts of attempted capital murder.

Justice in Public

I suppose this brings me to the point: the satisfaction in justice is found in the glory of the law, and the process by which it is brought to bear on those who transgress it, not in lust for blood, for action. The navigable stream of evidence, investigation, and deliberation is what takes us from the transgression to absolution or conviction. This process may not deliver justice perfectly, but to abandon it is to abandon the attempt. We may not know much about how to solve racism in America, for example, but we can know that it is unjust to destroy an innocent man’s business, and therefore we know that that injustice will not serve the cause of justice. We may not know how to clean up political corruption or create a political culture where all Americans feel adequately represented, but we know that breaking into the Capitol building and attempting to murder the Speaker of the House will not do that job.

There are no shortcuts here, because how it all feels, seems, or looks to those passionately watching the news can’t be allowed to determine what is decided in court. The only relevant metric is how it actually was, as best we can tell, based on evidence that can be publicly produced and evaluated. I admit that at times this process can be difficult and, when weighed in the balance with immediate satisfaction, often found wanting. The slow and tedious work of investigation, interviews, and analysis is the work that every police officer in this nation dedicates their professional life to. The work of the justice system to determine the facts of the deed, and the intent behind it, is a work of public moral and legal evaluation. It is hard. It is imperfect.

Finding at least some of the truth is not impossible. But it does not come from social-media mobs who decide on the guilt or innocence of people based on cellphone video clips, and it does not come from those who create mental conspiracy charts based on Reddit rumors.

The art of public life, it seems to me, lies in balancing the need for protecting space for the public conversation that is the heart of politics—conversation that we ought to strive to conduct rationally and in friendship, even in the face of profound disagreement, but in which there must also be room for the antagonistic, and the downright loony—with the need for protecting space for the careful and dispassionate sifting of evidence, the slow and annoying work of police and lawyers and juries.

Both sides of this public work need each other. If police, or elections, become corrupt—if police departments are racist, or politicians are self-serving—the public must hold them to account. But what the public must not do is to despair, to give up, to decide that the work of conversation and politics and marginal improvement is useless.

It is my hope that as the new administration contemplates the action that it will take in response to both the events of the summer and of January 6, they are guided by this same conviction. It is our job to protect the public realm, and that means protecting the space for exchange—even heated exchange, even stupid exchange, even ill-informed exchange, even exchange based on premises with which we disagree or in terms that we do not understand. This exchange must take place in a public realm that is physically safe: people must be protected in their rights to speak and to assemble.