So there’s an American election coming up. I don’t know if you’ve noticed.

It seems like it’s been going on since about 2015, but they tell us it’s nearly at its end. Maybe.

Now perhaps you’re fatigued by American politics or have tuned it out amid our current COVID realities, but over the past five years or so, American politics have been hard to escape.

In Canada, we’re bombarded by the coverage and feel the tensions amongst our neighbours to the South: tensions of mistrust, inequality, violence, and division.

And yet—and this is the point for understanding the text before us—those palpable tensions we’re witnessing today on our screens and radios still pale in comparison to the fear and outrage pulled thin and tight over Roman occupied Judea in the days of Jesus.

I’ll try to paint the scene for you.

Judea had been under Roman control for about ninety years at this point. For sixty of those years it had been a subject kingdom of sorts: part of that time under the Kings Herod, who you probably know.

But at around the turn of the millennium—about the time that Jesus was born—Judea became a Roman province under direct Roman rule, following the rejection of one of Herod’s sons. Think of how the Christmas story of Luke 2 begins: with a census being taken while Quirinius was the Roman Governor of Syria. i.e. Direct Roman rule.

This formalizing of Judea’s subjugation to Rome and the new system of taxes that came with it—for which a census was needed—injected new and rising tensions into Judea’s relationship with Rome.

There’s a failed rebellion leader mentioned in the book of Acts—Judas the Galilean. He led a charge against Rome in these early years of Jesus’ life: “in the days of the census” (Acts 5:37). After Judas’ rebellion there were times of relative peace, but now—another thirty years later—the tensions were growing again.

These are the days of Jesus’ ministry.

And these are some of the reasons everyone expected and longed for Jesus’ movement to give them a political Messiah that would overthrow the Roman occupiers. The time was ripe for it. It’s also why the charge of being “King of the Jews” was worthy of death by public crucifixion in Roman eyes.

These tensions would eventually culminate in all-out war with Rome in the year 66 AD, which would lead to the destruction of the Temple in 70 AD.

All this to say that taxes paid to Rome were a big deal. And these taxes weren’t just abstract numbers on a screen—they were paid in real life coin that one had to physically hand over, symbolizing in a very tangible and visceral way the power of Rome over the Jews.

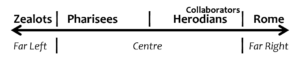

So people gave up their lives in protest and rebellion against this tax. People were willing to knife even their own fellow Jews if it was discovered they had collaborated with Rome. There was a Simon in Jesus’ own band of disciples who was one of these knife-carrying militia men from the left, called the Zealots.

Of course, the times were polarized. And so, on the other side of the divide there were collaborators—those Jews who were sympathetic to Rome. An example would be the uniformly despised tax collectors, those “sinners” who worked with and for Rome. Jesus had one of these in his band of disciples as well. It was Matthew himself. He collected the Roman tax at the crossroads in Galilee—one of the busiest trade hubs in the nation.

And there were other groups too. Slightly less extreme in their beliefs, but also on different sides of the polarized spectrum were the Pharisees and Herodians. The folks who show up in our text today. The Pharisees were no friends of Rome. The Herodians were.

So there you go: tensions ran high in the land of Judea. The occupying force with their military state of Roman legions and collaborating tax collectors verses the highly religious anti-Roman militia that was the Zealots. Not only could you feel this tension—but you could quite visibly see it, especially in Jerusalem in the Temple Courts, where this incident from Matthew 22 takes place.

Picture the religiously devout Jews, some subversive, going about their prayers, sacrifices, and teaching inside the Temple courts with armed Roman soldiers keeping watch above in their towers at the Antonia fortress.

You can see that fortress in the picture above of the Model of Jerusalem in the Second Temple Period from the Israel Museum. The Antonia Fortress shared a wall with the outer Temple Court. It’s the 4-towered fortress built onto the Temple complex in the upper right corner of the picture, in clear view of most all the worshipers quite literally underneath the Romans down in the courts.

Now, this section of Matthew’s Gospel is set in the final week before Jesus’ crucifixion. Following his triumphal entry at the beginning of that week, Jesus began teaching in the Temple Courts where we hear him speak some parables against the Pharisees and Chief Priests. Not long after, they begin plotting for his arrest.

So the approach of the Pharisees and Herodians in verse 16. These groups were on different ends of the political spectrum, but they had found their common ground in opposition to Jesus.

And of course, because this was all happening at the time of the Passover, every other Jew from the empire—Zealots, collaborators, and everyone else—were also in Jerusalem that day: listening in. As was Rome from their perch above in the fortress towers.

That was the audience when the Pharisees and Herodians buttered Jesus up with rich compliments about his honesty, integrity, and impartiality. And then came the question: “So Jesus, is it right to pay the imperial tax to Caesar or not?”

No pressure.

Of course, a “yes” would incite the far left’s Zealots to action against Jesus and his movement, and a “no” would be sure to catch the ear of Rome.

On both sides were swords and violence. The answer to this question was not neutral. In fact, there’s perhaps no question that could have captured the tension and polarization of the moment as simply and deeply as this one did.

A lot of power turns on money. So do you pay the tax or not?

Every eye was on Jesus.

“You hypocrites,” comes the reply. “Let’s get it straight right now,” Jesus seems to say: “you’re not interested in the answer to this question—you’re just trying to trap me. Trying to get the zealots and the Romans to do the political dirty work of disposing of me for you.”

Jesus was on to them. And yet, Jesus was also trapped. I imagine smiles beginning to curl in the corners of his questioner’s lips as they locked eyes with Jesus, both of them knowing there was no good way out of this for him. He was indeed trapped between the swords of the Zealots and the swords of the Romans.

Now there are any number of situations that arise in our relationship to government that can lead us into similar, albeit usually less perilous, conundrums.

Sometimes issues are between our faith and civic opportunities and responsibilities, as with the concerns from a few years back around the Canada Summer Jobs program attestation, or the difficulty in Ontario with Assistance in Dying legislation that requires medical professionals who are unwilling to assist in a patient’s death to make a referral against their conscience to a medical professional who will.

At other times, and in fact this is more likely the norm, the issue is between the proper application of our faith to any given social or political issue. This happens in Canada certainly, which is why you can find faithful Christians voting Conservative, Liberal, NDP, Green, and more. It is also why you can find quite a large variance in Christian observance of the health guidelines around COVID-19.

Those differences become particularly contentious at particular times or around particular issues or figures though, as we’ve witnessed in the States around political allegiance, mask wearing, and any number of other things. Sure, social media adds accelerants to the blaze, but humans are quite capable of this behavior all on their own.

It’s Christians who have so thoroughly identified with their own party so as to nearly or actually disown fellow church members and family members of a different political stripe. It’s happened among both Republicans and Democrats.

Opinions on the American political divide has even divided some Canadians in similar ways—even though they have no vote or say in the matter.

The polarizing rhetoric and personalities draw us into these divisions and lead us to believe that we have to line up on one side or the other. For or against: even if the “for” would pit us against our family and the “against” would pit us against our convictions. Sometimes there is no good answer. Sometimes we’re just trapped.

Image: Myers, Allen C. The Eerdmans Bible dictionary 1987 : 730. Print.

Image: Myers, Allen C. The Eerdmans Bible dictionary 1987 : 730. Print.

That’s the nature and the difficulty of the question given to Jesus. Is it lawful to pay the tax to Caesar or not? Yes or no? For or against? The stakes were high.

But after calling them out as hypocrites, Jesus continued in his response by asking for the coin. They brought him one. “Whose image is this? And whose inscription?” Jesus asks.

“Caesar’s,” they reply.

“So give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s.” says Jesus, simply.

And just like that—it was over. A third way opened up as Jesus gave his first and only political pronouncement. His questioners were dumbfounded and amazed. They turned and walked away, stunned. Somehow Jesus had managed to get out of the trap. There would be no clash of kingdoms and swords on this day. Not yet anyway.

Now beyond the unfathomable speed and wisdom of Jesus’ response—Jesus also has, in this incredibly compact statement, given both they and the church a basis for understanding our relationship to the State that goes beyond just taxes and beyond just picking sides.

First, it’s a word for those who—especially in this current moment—would rather just throw in the towel and be done with the whole political endeavor. Politics have been far less contentious through this pandemic so far in Canada, but it doesn’t mean you haven’t been burned. Whether by extreme rhetoric, mud-slinging, or raw exercises of power either here or to the South. So you don’t vote and you turn off the news or walk away from the group when they start talking politics, you’re just not interested.

There is a position we can hold in relationship to the government where we give too little respect to it. Whether because we’ve been turned off by the politics or perhaps because we just never really cared for following the laws of the land in the first place.

Because there are also those who willfully neglect the laws and regulations of the land, especially when said laws make them do things they’d rather not do, like pay taxes or wear a mask.

So for all of us who are tempted to give too little respect to the government, whether from disinterest or dislike—Jesus speaks these words. Jesus is not suggesting that we give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s—he’s commanding it.

In other words, as the rest of the New Testament witnesses to, government is a God-instituted institution and must be respected. Government is entrusted with the upkeep of infrastructure like water, sewer, and roads, as well as the keeping of standards in education, food safety, and health care, among other things.

All of these are good things, necessary for the common good and the flourishing of society—something we’re especially aware of now amid a pandemic. So Jesus commands us to give back what we owe in payment for services rendered.

And if that kind of respect was to be given to Caesar—the pagan Emperor who set himself up as a god and gave no say or vote to any subjugated peoples, like the Jews, how much more force does that command have today in a Democracy where we the people hold political power over the government via our right to vote. Our form of government is participatory—and so participation and respect is what’s due to the Caesar of democracy. And Jesus commands it.

Second, while Jesus’ statement lifts up the importance of government, it also limits it.

This is also a word for those who are tempted to baptize as Christian or to make absolute the claims of any single political party, political solution, or political leader. Because, to make an absolute claim for anything, is to put it in the place of God.

When Jesus goes on to say, “and [give back] to God what is God’s,” He means to say that there are indeed things that do not belong to Caesar. As Caesar’s image was on the coin, we know that God’s image is imprinted on us. So God demands much more than our money. He demands that we surrender all—all our heart, soul, mind and strength, lovingly, to him.

When that doesn’t happen and we give our total allegiance to a particular political solution, leader, or party instead, things are not only out of balance, but this often places us in dangerous territory.

A glance across the border again, can show you how. Families are divided right now in the US: can’t talk to each other because political allegiance has risen above family ties. The same is true in churches in those places where political allegiance has—on both sides—surpassed allegiance to God: made no better now by the politicized nature of pandemic response. When that happens, government transcends its God-ordained boundaries and becomes an idol. The results, as you can see, are division and discord.

Not that long ago, I heard a fellow pastor from our denomination say that “all human wars stem from efforts to take the place of God.” I think he’s on to something.

When our allegiance to a particular politics or country is higher than our allegiance to morality, or to the inherent human dignity of all people because they are created in God’s image, and certainly when our political or national allegiance is higher than our allegiance to God—abuses like those of authoritarian and totalitarian regimes are given license to flourish.

Or—as is more often the case in our experience—it’s the daily abuses of lesser degrees in individual cases that pervade—like anti-indigenous discrimination in health care and other governmental systems.

So Jesus has set limits on the authority and scope of government. Indeed, God will not tolerate any other gods, governments, or nations to come before him. We shouldn’t either.

Jesus commands us in relationship to government not to give too little or too much respect. We’re called on to give back our due to the State, and we’re also called to keep any political or nationalistic claims from becoming absolute in our hearts and minds—they are not and cannot be on the same level as God.

That doesn’t solve the thorny issues that divide us—from the US’s political divide and politicization of masking to our own questions around the extent of government’s response in a pandemic—but it does keep us within the boundaries of proper play.

To that end, Jesus also gives us a deeper thought to ponder: “Give back to God what’s God’s,” he says. And really… what doesn’t belong to God? To the God who, in Christ, has claimed every square inch of our lives and of this universe? As Richard Mouw once put it: “Does Caesar putting his picture on something really make it his?”

We give back to the government and participate in government, not because of government or for its own sake. Every political entity and methodology is fallible and finite—it only takes a revolution, a war, or a brief glance at history to realize that.

So we don’t serve, participate in and give back to the State for its own sake. We do it, because God calls us to do it as part of respecting him and the authorities that he has set over us in this world that belongs to him. The State is not an end in itself. It is a God-given means to the promotion of the common good in human society.

Only God is completely good and just.

Only Jesus can reconcile divided and diverse people together into unity (not uniformity), as he did way back with Simon the Zealot and Matthew the tax collector, calling both to follow him.

Our trust then is always first in God through Jesus Christ. Because it is he, not the government, who ultimately saves us and who is ultimately worthy of our complete allegiance.