This summer, I returned to my rural hometown of Gardnerville, Nevada, for rest and retreat, leaving behind the intensity of Washington, DC: the August heat and humidity, the tiresome awareness of COVID-19, the grief of racial injustice, the helicopters circling above my apartment, and the ever-present political fray.

I expected tranquility. Instead, I found a clash.

The day after I came home, an estimated two thousand counterprotesters gathered, overwhelming the forty-ish Black Lives Matter protestors on Main Street. Militiamen dressed in camo, mostly locals, flooded into town. Some citizens slung assault rifles over on one shoulder and strapped handguns to their belts; others held signs that ranged from earnestly patriotic to viciously partisan.

As I drove by twice, I felt sad, but mainly confused. No longer a resident of the community, how should I respond to the situation? How, in particular, should I react to my father’s participation as a counterprotester against the BLM activists?

It made for a heated debate on the first morning of my vacation.

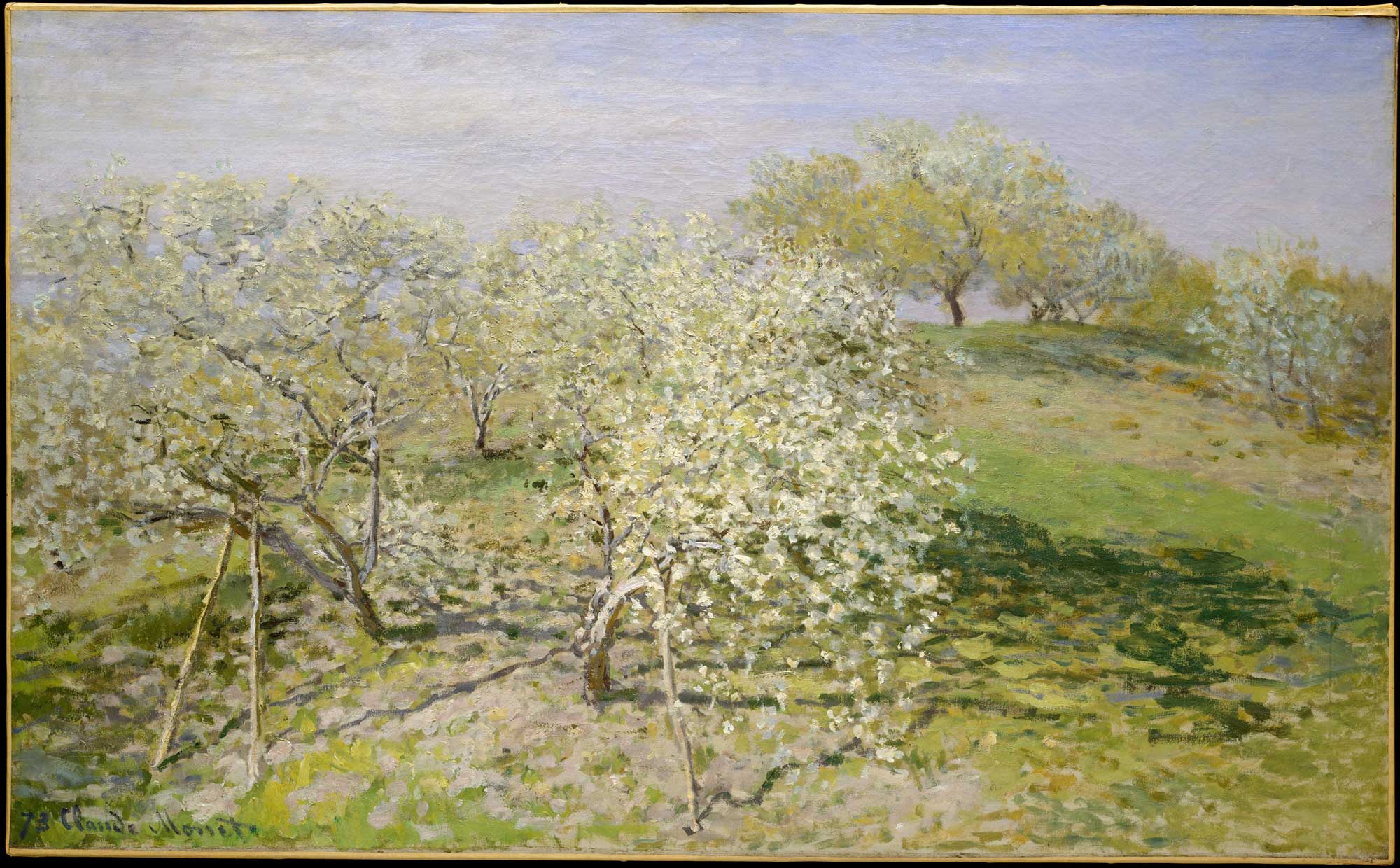

My hometown is a place of sublime beauty. Home is where desert turns to valley, and valley turns to sheer granite mountain. Twenty minutes over the mountain sits Lake Tahoe. It is a liminal space where God’s presence feels tangibly closer: much closer than the marble canyons of DC.

I woke up early the morning of my arrival, still on East Coast time, and sipped coffee as I watched the sunrise over the desert mountains on the other side of the valley. I was staying at my grandparents’ brick home tucked at the base of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, the setting of some of my most cherished childhood memories. In true rural Nevada fashion, my parents slept outside in an RV, while my husband and I slept in a nearby camping trailer. The acre plot of land is dotted with sagebrush, and the sun starts and ends each day atop the mountain rims on either side of the valley. The two ridges are distinctly different: one is starkly naked and acts as a barrier against desolate desert; the opposite ridge, where my grandparents’ home sits, is covered with pine trees and hides alpine lake after alpine lake in the folds of mountain granite bowls. As I’ve become older, I have grown to be captivated by the easily overlooked beauty of the raw desert mountain landscape. It is an austere but vivid and changing canvas of purples, yellows, and oranges.

I watched as the sun rose higher, eyes prickling with gratitude as I inhaled the sagebrush scent and crisp morning air. With the difficulty of travel in the midst of a pandemic, I had been terrified I would not make it home to the place where time and again the sun, dust, and silent contemplation in the presence of God have restored my soul. But here I was. Home.

The protest, and the counterprotest, happened later that day: this part of the country proved itself no more immune than the rest to the fear and alienation that are overcoming us. Tensions boiled to the surface in my small hometown when, in early August, the director of the Douglas County Library proposed that the library issue an official statement in support of Black Lives Matter. It was unclear whether this statement was meant to support the organization or the movement, and, of course, this came in the middle of a summer when support for Black Lives Matter became synonymous with calls to abolish or defund the police. In response, Douglas County Sheriff Dan Coverley issued a public letter to the library board. “Don’t bother calling the police” if you’re in trouble, he said—a threat he quickly walked back. Not, however, before it made national headlines.

On Saturday, August 8, about forty people from a nearby Black Lives Matter group arrived to protest the Sheriff’s comments. In response, the rural community quickly formed a counterprotest, afraid that stores on Main Street would soon be looted, as they had seen happen in cities across the country.

Fresh in my bodily memory that morning was a march organized by Thabiti Anyabwile, pastor of Anacostia River Church, which had taken place in Washington, DC, at the beginning of June. I participated with a sign that said Black Lives Matter on one side. I’d written the “Prayer for Social Justice” from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer on the other side. We chanted, “Love mercy, do justice.” We sang “This Little Light of Mine” as we walked down Pennsylvania Avenue. It was the first protest that I had ever participated in, and it was powerful. We hadn’t been meeting. It felt like church.

In Douglas County, 62.5 percent of voters voted for Donald Trump in 2016, which never surprised me; however, I still found myself shocked at the number of flags, signs, posters, and stickers supporting President Trump at what appeared to be almost every single house, farm, and business. It’s possible I simply did not accurately remember the lead-up to previous presidential elections, but it seemed as though politics had somehow seeped deeper into the soil of every conversation and public space. The pre-political aspects of life, even in the home, held onto a faint margin.

Strangely, this trip home made me feel like a coastal elite. A cosmopolitan. Even though I work at a conservative public-policy think tank, my language and cultural ties have changed over the years. I grew up as a nondenominational evangelical on the West Coast; I now attend a theologically orthodox, and relatively conservative, Anglican church on the East Coast. On paper, my résumé is filled with politically conservative affiliations. In reality, I am another millennial who finds myself “politically homeless.” Now when I visit home, this uncomfortable cognitive dissonance between my current ways of thinking and the values of my family and hometown have slowly overshadowed the warm glow of remembering a childhood spent walking lake rims and camping under the stars. Politics has moved into crannies where it should not have reached.

In a time when politics have bled into every sphere of daily life and become closely intertwined with individual identity and even religious affiliation, how we respond and productively engage in the public square with those who hold different political views matters.

But how do I respond to my dad?

In a time when politics have bled into every sphere of daily life and become closely intertwined with individual identity and even religious affiliation, how we respond and productively engage in the public square with those who hold different political views matters.

The sun, now higher in the sky, starting to bear down with the dry desert heat that I have grown to appreciate after experiencing DC humidity, was beginning to make me sweat. The prayerful posture of gratitude from my quiet time was replaced with the jitteriness of too many cups of coffee and not enough food.

I had prepared for conversation with my father for weeks, and had several questions to pose to him: Is America truly a Christian nation? Should it be? Are we really at “war” with our political opponents? And even if we are, should Christians participate in this political “war”? What is our public witness, and what does it say about our values? Should we think of politics as being ultimate? What is “politics”?

I don’t know the answers to all these questions.

Although I grew up in a church that shied away from political conversations, I have spent the last several years of my life reading St. Augustine and Reinhold Niebuhr (among others) and have been knee deep in contemporary debates on liberalism, integralism, nationalism. Complicating conversations with my father, and with others from my rural hometown, is that I am conscious that most people don’t typically engage with these texts or debates in daily life. I didn’t want to come off as if I had everything figured out. I don’t. What I wanted to say was this: “We are already saved.”

Before I could roll back my tongue and, with love and respect, enter into a conversation with my father as I had been preparing to in the preceding weeks, things escalated. Both my mother and husband ran for the hills when it started. I never brought out my notes.

Dad and I both started to get upset as we argued about video footage of the death of George Floyd. I knew we were about to enter the point where we both had deaf ears, loud mouths. I knew then, as I know now, that political debate doesn’t change minds. I knew that I loved him. I knew that I don’t know everything. I knew that I might easily be a fool.

So, on a whim, I asked my dad if he wanted to pray with me.

It was a long prayer.

Prayer is practical political theology.

After we finished, we continued our discussion with significantly less tension and considerably more empathetic listening. We covered what it means to have a physical presence at a protest, how our Christian faith can inform political practice, and the different manifestations of public witness. I didn’t change my father’s mind, and he didn’t change mine. But we left the conversation still as father and daughter, not political rivals.

When we joined the communion of saints in prayer, we entered a narrative larger than our current political moment, larger than the protest about to occur. We declared, together, that Christ is King. That was a political act. We acknowledged together that we are indeed already saved, and as a result, the rules of political combat were changed. In fact, it became evident that combat is maybe not the right method at all.

In this liminal space at the base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, heaven slightly broke through and defused the worded missiles that my father and I had hurled at each other.

The cultural and language barrier surrounding faith and politics seems to grow ever higher when I talk to my family. Prayer is practical political theology that begins with transcending political differences and has shown me a sliver of hope in this time of extreme polarization. It provided my father and me with a common language. It is an invitation for Christ to enter in to the middle of our political and pre-political messes.

Many of us have just been through a good-and-bad-and-complicated Thanksgiving. We’re headed into Christmas.

Pray.