In his poem East Coker, T.S. Eliot writes that “the whole earth is our hospital.”

Eliot is referencing “Adam’s curse”: the death and sin which resulted from mankind’s fall in Genesis 3. But the line seems particularly affecting amid our current COVID-19 global pandemic. From continent to continent, we are facing the visceral reality of death, quarantining of individuals, and collective fear of infection. The whole earth is indeed our hospital, and we all are in desperate need of healing.

In his essay “Health Is Membership,” Kentucky essayist, farmer, and philosopher Wendell Berry suggests that individual health cannot ever be divorced from one’s larger membership with the earth and its various communities. Therefore, as we remind ourselves of the curse and its implications, we must not just turn inward—but also toward each other, toward community. Health, Berry suggests, requires re-membering: resisting a culture that “isolates us and parcels us out.”

But how does this apply to our current moment, in which we are all, in fact, physically isolated and segregated from each other? How do we begin to deal with the spiritual, physical, economic, and communal devastation caused by the COVID-19 virus? What ought we to remind ourselves of, and what ought we to remember in a more communal sense, going forward?

Berry wrote “Health Is Membership” approximately twenty-six years ago. But its prescriptions and condemnations are well suited to our own complex, troubling moment.

Berry first considers the root of the word “health” itself, which stems from the same Indo-European root as “whole.” Health, then, is literally “to be whole”—but this wholeness cannot and should not be attributed to individuals in isolation. Health-as-wholeness must have larger implications: “not just the sense of completeness in ourselves,” Berry argues, “but also . . . the sense of belonging to others and to our place.”

Full health rejects the division and disintegration of culture, community, and ecology. It rejects the separation of family from family, as well as the specialized view of the self that severs body from soul—or even parts of our body from other parts.

Yet we often like to see the various parts of our world as separate entities: churches, nuclear families, schools, grocery stores, office buildings, hospitals, assisted living centers and nursing homes, apartments and townhouses all subsist in detached zones. Beyond all this, there are the shared parks and forests, rivers and streams, roads and gardens, which we see as lovely and important, but rarely view as “ours.” We approach our world like a machine: divorcing ourselves from every other part, pulling apart the various strands in the tapestry.

We approach our world like a machine: divorcing ourselves from every other part, pulling apart the various strands in the tapestry.

Most approve of this segregation, thinking how well we have “streamlined” society. But we cannot reclaim health without considering practices that hurt those beyond and around and underneath us: in the soil, the water, the air, the neighbor’s house, and beyond. Modern thinking on health “excludes unhealthy cigarettes but does not exclude unhealthy food, water, and air,” Berry writes. “One may presumably be healthy in a disintegrated family or community or in a destroyed or poisoned ecosystem.” But reality, of course, is far more nuanced and interconnected than this definition allows.

The Scientific American reported, shortly after the COVID-19 virus began to spread across the world, that it is indeed a “destroyed or poisoned ecosystem” that makes our world especially vulnerable to viruses of this nature.

“[A] number of researchers today think that it is actually humanity’s destruction of biodiversity that creates the conditions for new viruses and diseases like COVID-19 . . . to arise,” author John Vidal wrote. “In fact, a new discipline, planetary health, is emerging that focuses on the increasingly visible connections among the well-being of humans, other living things and entire ecosystems.”

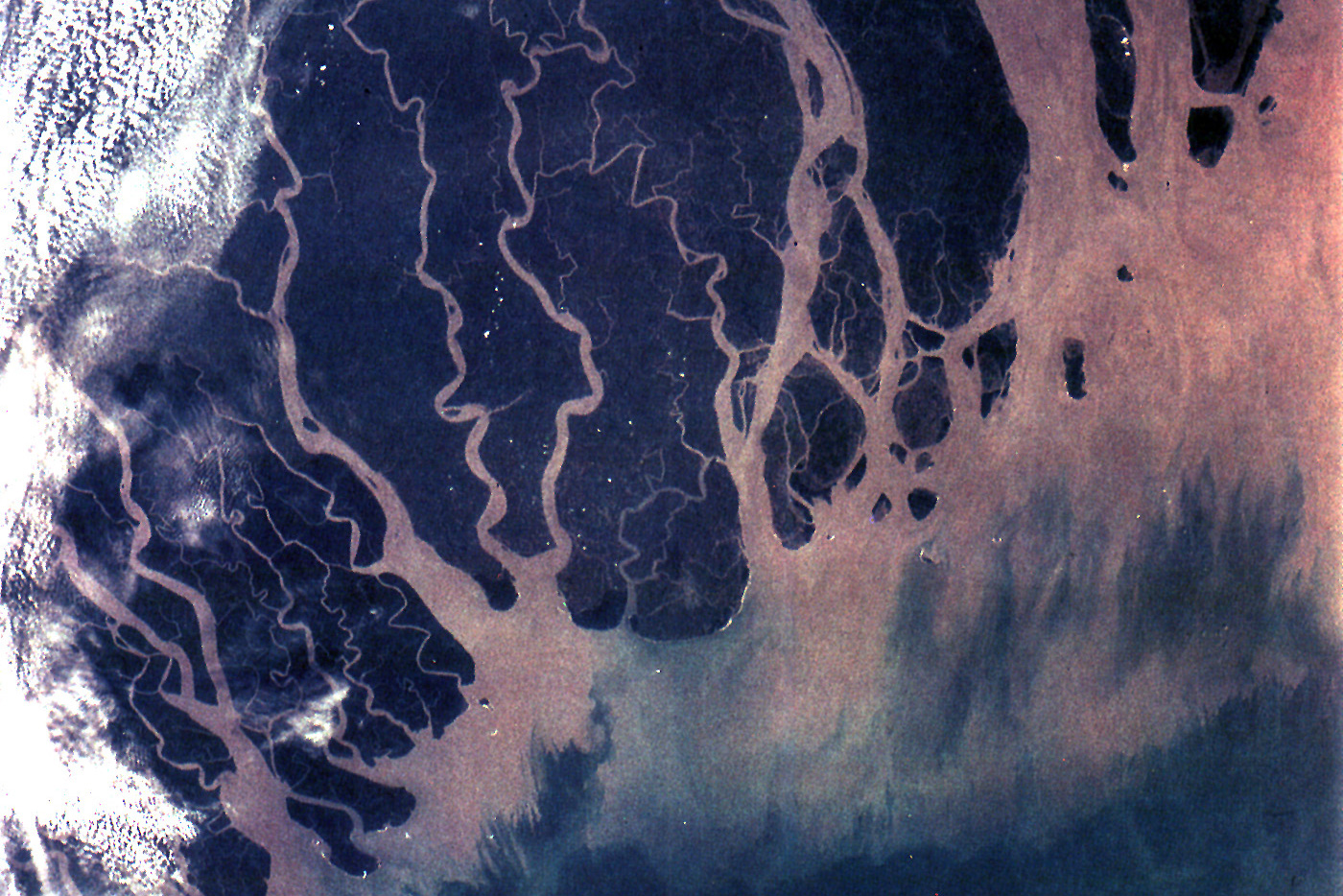

It has taken us approximately three decades to catch up with Berry. But we are beginning to realize that he is right. Our world is interconnected and interdependent—much like a body, as Berry describes in his essay “The Body and the Earth”: “Body, soul (or mind or spirit), community, and world are all susceptible to each other’s influence, and they are all conductors of each other’s influence,” he says. “This is a network, a spherical network, by which each part is connected to every other part.” Indeed, Berry suggests that we could compare our world to a circulatory system: disease in such a system “tends first to impair circulation and then to stop it altogether.”

It is interesting here to think of COVID-19, and the often strange, unpredictable, full-body impact it can have on those who suffer from it—from one’s toes to one’s lungs, symptoms have been sporadic, severe, and unpredictable. The frustrations it has posed to our health-care system are likely increased by the fact that our system is extremely specialized, and likes to view the body as a machine with disparate parts, rather than as a whole in which all affects all.

But the entirety of the COVID-19 pandemic has served to remind us that our health is predicated on each other: individuals grappling with anxiety and depression while shelter-in-place orders continue surely have felt their dependence in a new, sharp way. Parents seeking to work full-time, homeschool, and provide 24/7 care of their children are realizing their need for community assistance and support. The elderly, divorced from the rest of society in specialized nursing homes, are both at increased danger for this virus, and the most likely to suffer from intense loneliness. Children required by their schools to complete lessons online are cut off from the natural world and spring weather beyond their front doors, chained to a screen until their assignments are complete.

Here, too, Eliot’s statement—“the whole earth is our hospital”—rings true. It is not just because we share a fallen, broken reality. It is also because the health of each piece of this world affects every other piece. To lack empathy, care, or love for the destruction of one part of our world is both selfish, and unselfconscious: it reveals that we believe we are somehow separate from the fate of our fellow creatures, or of our shared earth.

The prevalence of this attitude has become especially clear as resistance to COVID-19 health recommendations or shelter-in-place orders has escalated. Thinking of the world reductively, or in a radically individualistic way, makes it easy to put individual rights, freedoms, or inconveniences before collective health—because we think of ourselves as isolated and autonomous, rather than as parts of a whole.

The wearing of masks, therefore, is derided as cowardice by conservatives who suggest wearing a mask is more about political correctness or personal fear than it is about safeguarding the vulnerable. This complaint is part of a larger narrative on the right which suggests that we should not sacrifice our own comfort or freedoms in order to protect a minority of immunocompromised or elderly individuals.

But this, too, is a reduction of health—or rather, a sacrifice of it in the name of individual comfort. It is important to note that the decimation of our economy through the last several months is indeed a problem, and indicative of the fact that every piece of our world is deeply connected. But the fragility of our economic system should not call on us to ignore the needs of the sick—to further sever or reduce our definition of wholeness or prosperity.

“The parts are healthy insofar as they are joined harmoniously to the whole,” Berry writes. Putting economics before community, before health, is not the answer—even while ignoring economic unhealth and fragility is not the answer. “Healing . . . complicates the system by opening and restoring connections among the various parts—in this way restoring the ultimate simplicity of their union.”

An economic system that can only profit on the ill-health or destruction of bodies is itself sick, and requires healing. An American food system predicated on the horrific treatment of slaughterhouse workers, farmhands, and delivery-truck drivers desperately requires reform. We should not live in or tolerate a system that forces us to sacrifice the health of the few, the voiceless, or the disenfranchised for the comfort or health of the many. It is true that we live in a broken, fallen world in which triage is a necessary reality. But the curse is not our only reality. There is hope—because there is love. And love, Berry suggests, is what steers our world toward real health.

“I take literally the statement in the Gospel of John that God loves the world,” he writes. “I believe that the world was created and approved by love, that it subsists, coheres, and endures by love, and that, insofar as it is redeemable, it can be redeemed only by love. I believe that divine love, incarnate and indwelling in the world, summons the world always toward wholeness, which ultimately is reconciliation and atonement with God.”

Health is wholeness, Berry says. But this wholeness, when and where it exists, is not the fruit of some mere intellectual exercise or expertise—it is the result of love’s dogged efforts to redeem, defend, and protect. Love is the answer to a reductive health-care system—and it is crucial to safeguard all those whom our world sees as disposable.

“To the claim that a certain drug or procedure would save 99 percent of all cancer patients or that a certain pollutant would be safe for 99 percent of a population, love, unembarrassed, would respond, ‘What about the one percent?’” Berry writes. “There is nothing rational or perhaps even defensible about this, but it is nonetheless one of the strongest strands of our religious tradition . . . according to which a shepherd, owning a hundred sheep and having lost one, does not say, ‘I have saved 99 percent of my sheep,’ but rather, ‘I have lost one,’ and he goes and searches for the one.”

Our struggles with the COVID-19 virus are far from over. But our attempts to find healing in days to come will not be limited to a vaccine. They must be deeper, wider: taking into account all the multitudinous severances which suggest that our world needs wholeness and love. The virus has revealed the fragility of our food system, the way efficiency has broken down health and resiliency. We’ve seen how broken our nursing homes and elderly care systems really are—evidenced in a horrific amount of deaths. The spread of the virus in prisons should show us, once again, how urgently we need prison reform. And the very existence of the COVID-19 virus shows us that the diversity and health of our ecosystems need to become more important than the temporary beneficence created by logging, mining, and other systems that deteriorate or destroy the earth.

But just as important, perhaps, will be individual acts of quiet fidelity on behalf of the voiceless or vulnerable—the one percent Berry refers to. Perhaps even as larger reforms appear daunting or distant, there are efforts each of us might make to heal and restore broken connections. Henri Nouwen has suggested that Christ is a “Wounded Healer”—the Savior who, even now, redeems our brokenness and offers healing. But he adds that through Jesus, we ourselves can become wounded healers: “Those who do not run away from our pains but touch them with compassion.”

Even in this dark and difficult time, such healing is taking place. Within our hospitals, it’s evidenced in the nurse who faithfully holds the hand of a dying patient until his last breath. It’s displayed in the priest who died after giving his ventilator to another sick individual. It’s visible in neighbors who regularly offer free food or diapers to those in need, local townspeople who are donating to food pantries, and churchgoers who are providing food to needy families, parents with newborns, or to the sick. It’s evidenced in the abundant growth of victory gardens, the letters sent to nursing home residents, and the widespread surge in community-supported agriculture support.

None of these steps, by themselves, represent a perfect return to health. None of them can fully fix problems of systemic injustice, which lead to larger trends of ill health in our country. But they are a beginning. They reflect a realization that we are indeed part of a membership, and that our health is therefore predicated on more than our own physical resilience. To be healthy, we must acknowledge—and love—the entire web of life we are part of.

The world may indeed be our hospital. But if so, each of us can be a “dying nurse,” in Eliot’s words: seeking to bear each other’s burdens, drawing our whole broken earth toward wholeness.