“Happy Wednesday! Or as it’s called now, ‘Day!'” A colleague sent me this note back in the early days of quarantine, when new sourdough starters adorned kitchen counters, Zoom get togethers were still exciting, and the end of working from home was a mere month or two away, surely. Those Wednesdays, though—those “Days”—accumulated over the year, and her quip started to bite.

The pandemic had a way of flattening space and time. Space went first: 2020 turned kitchen tables to classrooms, studio apartments to offices, and living rooms to chapels. Time was the next casualty: “March was 30 years long and April was 30 minutes long,” Vox’s Emily VanDerWerff reflected. This December, Spotify Wrapped announced that “time wasn’t real this year.” The year seemed devoid of all demarcation. This kind of unfocused fog proves to be nearly insufferable. “Our own experience,” James K.A. Smith wrote back in 2014, “suggests that the unstoppable homogeneity of time is unbearable and unsustainable for us as humans.”

Yet, despite the unfocused fog that lingered over the past nine months, Christmastide comes along anyway. December rolled in, and with it, the liturgical season oriented towards celebrating the first and final coming of Christ. In the midst of a year that’s felt unbearably flat, the practice of feasting in gratitude for the light of Emmanuel, who came “in the fullness of time,” seems a monumental feat. The beginning of the Christian liturgical calendar, Alan Jacobs has noted, “uniquely concerns itself with past and future events.” How can we concern ourselves with both the past and future as the numbing homogeneity of time marches on? The answer, in part, can be found within the pages of novels.

For many, books were an early quarantine companion. Several sat on my bedside during what I call my “aspirational phase” of the pandemic. I leafed through a Russian tome on suffering, an Anglican psychiatrist’s wisdom, and a Greek myth retold. Despite several attempts to make it past the first few chapters, these books all spent the course of the spring collecting dust. My frustrations with the growing travails of the pandemic, in tandem with an increasingly scattered attention, only mounted as the year continued. On a desperate whim, I picked up a favorite for a re-read.

“I’m reading Harry Potter,” I confessed to my friend later that summer, three books in at that point: “pure escapism.” The magic of the wizarding world was undoubtedly a refreshing relief to a year that felt distinctly dis-enchanted. Hogwarts was a more bearable place than my stay-at-home-order living room, and celebrating Harry’s quidditch victories proved a helpful distraction from my new habit of mindlessly checking my work email at 10pm. My friend’s response was immediate: “No, no, no,” she said, “reading fiction is not escapist. It helps us see the world as it truly is.”

She’s right. Of course, fiction gives both a fresh perspective and the room to heal from life’s grievances. It offers far more, however, than just a refreshing relief. Indeed, “literary experience heals the wound,” C.S. Lewis wrote in An Experiment in Criticism. More than simply a palliative, fiction simultaneously brings solace and remedy. But what wounds does literature heal, exactly?

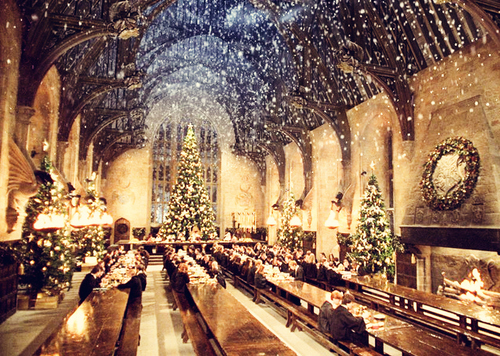

First, reading fights back against that insufferable homogeneity of time. We read a novel sequentially. As such, we become more aware that both the plot and our reading takes place in time. The wizarding world’s rhythms in particular draw the reader’s attention to time passing. Year by year, book by book, Hogwarts opens its doors to students, sorts the first years into houses, and, in the middle of each volume, lines the great hall with Christmas branches and ornaments.

Second, reading fiction heals us from the wound that comes from living in a world sealed off from enchantment—a world that looks at matter, throws up its hands and says “yup, this is all there is.” This wound comes from accepting a flattened space and time that precludes transcendence. If this world is as truly all we have, we are left to ruminate in our own weariness. Literature, at its best, yanks us out of this despairing and ruminating.

Fiction in particular corrects our false understanding that the world is in its essence only material: that it is not for anything, that it doesn’t mean anything, that it isn’t going anywhere. The subcreation that is a narrative world, by contrast, is made by someone who intends it to mean something; its events and objects are not just blocks of stuff and miscellaneous happenings. There is a plot. There is a “there” there. Seeing that form in fiction reminds us to look for it in real life. This reminder seems especially pertinent in a year marked by loss, isolation, and grief for so many.

Third, fiction heals the wound of what Lewis called “our own competitive particularity” and the loneliness that follows from it. Each of us, Lewis noted, seeks to be more than simply ourselves. We have a hunger for more: to experience more lives than ours, to look beyond ourselves. Stories help us to do exactly that. “In reading great literature,” Lewis wrote, “I become a thousand men and yet remain myself. Like the night sky in the Greek poem, I see with a myriad eyes, but it is still I who see. Here, as in worship, in love, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do.” Literature, especially fiction, takes us out of a flattened world and a flattened self, into a world radiating with light and life.

My time revisiting Hogwarts has been a reprieve from what has felt like an onslaught of a year. It has also revealed to me just how enchantment-averse I had been these past months. One thread of Rowling’s stories that struck a particular chord was the sharp contrast she drew between the magical and non-magical. The magic-averse Dursleys, Harry’s aunt and uncle, are “proud to say they were perfectly normal, thank you very much.” Their instinct is to turn away from any hint of the non-normal, to vehemently refuse the magical entrance into their neat world.

I can’t help but think I’ve been trudging through the year just like this worst kind of muggle, averse to the enchantment lingering right in front of me.

“Advent always begins in the dark,” says Fleming Rutledge. This year has felt like a long Lent: a fast that blended in to the fast of Advent. What preceded this Christmastide was a time marked by acute loss – temporary for some and permanent for many. What does it mean to be re-enchanted in the face of this loss?

In Philosopher’s Stone, you’ll remember, Harry comes across a magical mirror that shows its viewer the deepest, most desperate desire of their heart. Some look and see material gain, others a picture of the sort of belonging they have always longed for. Many men waste away before the mirror, tantalized by a glimpse of the life that could be.

I spent much of the year dwelling on hope deferred. If I sat in front of the mirror, it would likely reveal that the deepest desire of my heart throughout the pandemic was that this time would soon end. However, wishing away the times, or even simply enduring them, is what these twelve days of Christmas won’t allow us to do.

“The happiest man on earth,” Dumbledore says, “would be able to use the Mirror of Erised like a normal mirror, that is, he would look into it and see himself exactly as he is.” What would it mean to see this Christmastide, our Christmastide, exactly as it is?

We cannot and should not pretend away suffering. But we can’t pretend away hope either. We would see that our suffering world is teeming with light; we would see that God wonderfully creates and yet more wonderfully restores. “Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them.”