As a kid, I grew up in the Pentecostal church. The kind of church that was caught up in the rapture of Spirit-filled moments: Sister Debby shouting Psalm 23 before testimony service, Bishop Thorton’s yell, Deacon Black’s off-key singing that somehow always made someone shout because it was sung from deep honesty, humility. There was something about this space, this gathering of the “left out ones” in society, that was incredibly transformative for me.

I was one of those kids who had a deep respect for the preacher. When the sermon was on the way to its crescendo—what Black folks call the whoop—I would imitate him. I would grab the Martin Luther King fan my mom had sitting beside me, rip off Martin’s precious and stern face, throw my hand on my hip as I moved my oversized jacket, and I closed my sermon: I was caught up in this moment of ecstasy. While in this moment of lostness, you couldn’t tell me that I wasn’t preaching to my own congregation. There I was, young, preaching, free. Maybe that was the meaning. Maybe that was where I found my deep love for justice, blackness, liberation. Dreams.

I often think about those years, especially now that I’m older. The Pentecostal church. The people. The intimacy. Why were they so caught up in praise? What was it about this space that did that? What was this sort of mysticism? I don’t know if I know the answers to that, but I do know that something struck me more than anything: the joy.

I wonder if today this is a part of what we are missing—narrating joy. As we are living in what Professor Elizabeth Alexander calls “the Trayvon generation,” she writes that we know the stories of violence visited on Black flesh, that “anti-black hatred and violence were never far.” We understand what White supremacy will do to us: It will kill us. Slowly. Violently. Publicly. It is, as Langston Hughes writes, the walls oppression builds. Sturdy. Seemingly impenetrable.

We understand what White supremacy will do to us: It will kill us. Slowly.

It forces us into resilience. It is not normal. No people should be forced. There is a certain type of depression that descends upon those forced to deal with the tragic conditions to which Black people are subjected in this country. In this moment of struggle, it becomes critical—I would even say spiritual, moral, and political—to narrate and normalize Black joy in the face of brutality.

Blackness as a place of joy in this moment is not simply found in public protest, bodies being on the line, baby girls screaming “No Justice, No peace!” It is also found in a moment of intimacy. Even as protest is still going on, reading this moment, reading ourselves as the site of joy is revolutionary. It is not simply resistance; it is also power.

“The intent here is not to disregard these terms,” Kevin Quashie writes, “but to ask what else—what else can we say about black culture, what other frameworks might help to illuminate aspects of works produced by black writers and thinkers?”

This brings to mind Kendrick Lamar. I’ve been playing “Alright” on repeat. There is something profoundly joyful, even powerful, about being all right in the midst of brutality. It is hope. It is Black joy in an anti-Black world. Alexander reflects deeply on the meaning of Lamar’s ode to freedom—an epistle of love, of liberation. She writes, “‘Alright’ has been the anthem of many protests against racism and police violence and unjust treatment.” It is a spiritual for my generation.

There is something profoundly joyful, even powerful, about being all right in the midst of brutality. It is hope. It is Black joy in an anti-Black world.

The young one flying in Lamar’s video is “joyful and defiant, rising above the streets that might claim him, his body liberated and autonomous.” To be free is not simply an affirmation but a living expression, a discipline, a practice, a dance. It is profoundly spiritual.

Then things change: a police officer raises a finger to the young man in the sky and pulls the trigger.

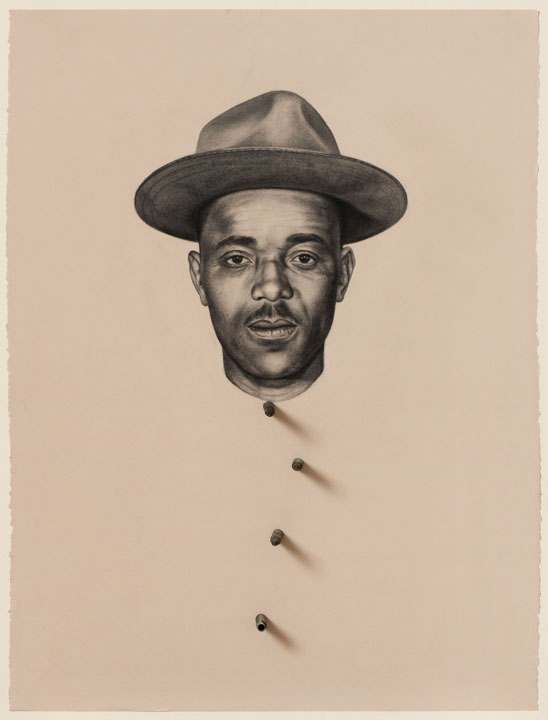

Kin LIII (The Way I Love You) by Whitfield Lovell, 2011. © Whitfield Lovell. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York.

The one flying falls—like Maya Angelou’s caged bird—and lands. “The gun was a finger; the flying young man appears safe,” she writes. “He does not get up.” In the end of what she calls “this dream,” the young one opens his eyes, smiles. Death? No. Life. “Black celebration,” Alexander concludes, “is a village practice that has brought us together in protest and ecstasy around the globe and across time.” Joy is a weapon of love. Blackness is beautiful, free. Powerful. Lovely.

Alexander reminds us that Black creativity was born out of response to an anti-Black world. To stand in the face of danger, to hold on to one’s imagination of a better world, to hope in the midst of unbearable social suffering, to remember one’s dead in a world that forgets—these become gospel to a people bent and broken. “Theology cannot, must not,” M. Shawn Copeland writes, “remain silent or complicit before the suffering of a crucified world and the suffering of God’s crucified people.” Creative responses to such suffering, the Black artist’s imagination, “evokes our integrity, calls us to responsibility for one another, calls us to entrust our lives to the dangerous Jesus.”

In this moment, there is a profound intimacy. The beauty of this moment shows that suffering is not the total image. This is a moment of faith. What is compelling is the unexpected glimpse we get of the inner dimensions of public bravery—the willingness to rise again. There is something about this song and image that calls out to us to sit still and be brave; it calls us to quiet anticipation of something beyond brutality. But the call to the quiet is not reservation to the chaos or confusion of life. It is a call to radical faith in the midst of darkness. It is a call to joy. It is joy, as Malcolm X would say, “by any means necessary.”

But the call to the quiet is not reservation to the chaos or confusion of life. It is a call to radical faith in the midst of darkness. It is a call to joy.

This serene moment tells a story. Inside of this song are the hopes, the dreams, the freedom of those bound. It is joy unspeakable. Mary’s Magnificat has become our own: He has brought down the mighty from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly. He has kept the promise he made to our ancestors. The Black body is loved by a God who stands in Christ with us in a loveless world, in the midst of tears, rage, death, oppression—a God who promises to shepherd us, strengthen our resolve, liberate the world to beauty. For that is the Christian story. “The Christian story,” Eboni Marshall Turman shares, “is that despite the coming of death, there is resurrection, there is life. There is an afterword. There is joy. That is Black joy.”

This joy is love in a dance with reality, humanity. It is the complex and complicated relationship with hope, a tragic but necessary one if it is to be what it can become—beautiful. If there is resistance, it is resistance found in the quiet places of our interior lives, the space where the divine reaches out to us to rest our weary bodies. When Jesus says that those who come will find rest, I often wonder what rest looks like for bodies suffocated in the brutality of White violence and racial terror. Is Jesus’s rest a sort of apathy to our dignity?

No. He must have meant that rest is both achievable as well as a noble journey—a journey of deep meaning, ultimate concern, and hope-filled compassion. It is a journey that is able to hold in one place our rage, our hopes, our failures, our pain, our love. It moves beyond seeing life—Black life—as one focused ultimately on whiteness and its violence, as if whiteness can save us. It cannot. It will not. The news is not good; it is hell. No. This joy sings in a world in which one is bound. It dances. It is free.

It’s like the freedom of the Black body that Baby Suggs speaks of when she preaches in Toni Morrison’s Beloved: “Here in this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in the grass.” It’s the taste of liberation that the spirituals speak of when they sing, “Freedom, oh freedom / Oh freedom ova me!” even though freedom is at a distance. It is Lamar smiling after rising again asking us, “Do you hear me, do you feel me?” Such a question was not meant to be answered; it was rhetorical. It was a reminder that we gon’ be alright. Flesh—Black flesh—gon be alright. These are both sorrow songs and lyrical protest, the spirituals and the blues.

Rest is a journey that is able to hold in one place our rage, our hopes, our failures, our pain, our love.

As Alexander writes of her sons (and us), “They are beautiful. They are funny. They are strong. They are fascinating. They are kind. They are joyful in friendship and community. They are righteous and smart in their politics. They are learning. They are loving. They are mighty and alive.” They are us, we are them.

We continue to struggle because we are free—even if we’re bound. Our very public protest for our freedom is beauty. If beauty, as Fyodor Dostoevsky noted, will save the world, then our Black is beautiful. It is profoundly spiritual. Black joy in an anti-Black world is revolutionary.

Maybe the Pentecostals I grew up around knew something: It is a journey that does not end. Many of the old Pentecostals have gone on, and I’m not a kid anymore. But they left me with something: They left me the power of joy. They left me knowing that the unexpected is possible.

These Pentecostals knew that we come from a long tradition of Black people who refused to accept the tragic belief and practices of White supremacy—the belief that we are second-class citizens, that we deserve exploitation and punishment, that we deserve disrespect and death, that we must be respectable and cater to the demands of whiteness. Finding it, though it may be elusive, becomes a great spiritual, moral, and political task in each generation. They knew each day, it begins again.

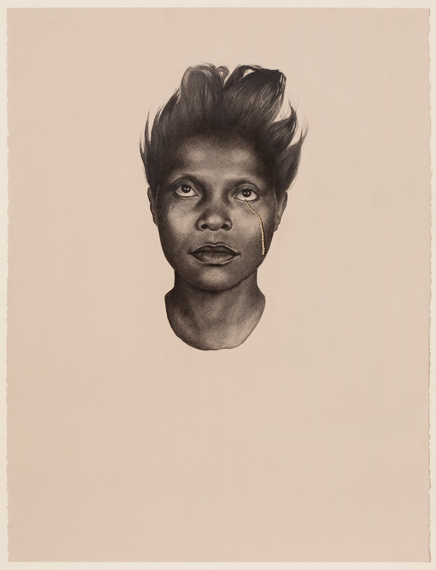

Kin XIV (No One Knows Where We Go When We’re Dead or When We’re Dreaming) by Whitfield Lovell, 2009. © Whitfield Lovell. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York.

It is this refusal, this courageous act of imagining a world that has never been, that has kept us going. It is impossible for a people to endure such gross injustice without dreaming a little. Yes, people speak of King’s dream of ’63. But since then, for us, it has been a nightmare. Yet we refuse to stop dreaming. It is our dreams that allow us to imagine the possible, to be critical of the present, and pressing toward a future in which love and justice are the guiding principles of a more perfect union, a real democracy.

In this vision to shape a new world, a sort of resurrection, it is our artists, healers, and revolutionaries that we need. In their creativity, our artists keep hope alive by exposing the myths and keeping us planted in reality, but dreaming of a day when life is made new. In their willingness to mend that which is broken, our healers take us to the place where people are wounded and broken believing that which is lost can be restored again. In their willingness to deconstruct the oppressive, our revolutionaries keep our eyes on the social suffering of God’s creation, showing us the way of solidarity to break the bonds of segregation, violence, and showing us how to build a life together that is just. To affirm one’s worth—not simply in the eyes of God, but also in the eye’s our society—is to scream from our soul, “Black Lives Matter!” It is to imagine the possibility of a future where Black life is not only present but also powerful. As Robin D.G. Kelley writes, “We must tap the well of our own collective imaginations, that we do what earlier generations have done: dream.”

Mary’s Magnificat has become our own. . . . The Black body is loved by a God who stands in Christ with us in a loveless world, in the midst of tears, rage, death, oppression—a God who promises to shepherd us, strengthen our resolve, liberate the world to beauty. For that is the Christian story.

Our tapping, affirming begins again each day: Black. Brilliant. Beautiful. It is our dreaming. Dreaming for ourselves and our children. We must remember: what we have endured does not tell of our worth, as James Baldwin would say, but it tells of others’ inhumanity and fear. In this moment of reconstruction, I believe with Baldwin that “though we do not wholly believe it yet, the interior life is a real life, and the intangible dreams of people have a tangible effect on the world.” How we dream today determines the world we see tomorrow. I just pray to God that we can dream again.

When you experience such inhumanity, the language of hope must be reimagined. It is not a celebration. It is not a theory. Nor is it even a point. It is a practice, a muscle, a discipline, a profound commitment to one’s future beyond resistance. It is to have in one’s body, in its movements, in its place, that which we dream of.

Hope is not content with the world as it is, as if it is the world that God wants.

Hope is not content with the world as it is, as if it is the world that God wants. Hope, at least for us, has been the willingness to never give up on ourselves, God, or even our country. At every moment in history we have given up so much for a place and people who have not loved us back. At every moment in history, our people have had a deep love for this country. This country is ours—flaws and all. That we are still here is not a testament of the moral goodness of America, this type of passionate pursuit of a more democratic world. No. It is that Black people have been willing to stare in the face of White supremacy, anti-Blackness, economic injustice, and the tragic belief experience of second-class citizenship, and have the will to survive in spite of it.

Kin XLV (Das Lied Von Der Erde) by Whitfield Lovell, 2011. © Whitfield Lovell. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York.

I recall artist Whitefield Lovell’s series KIN capturing this reality. Lovell, embodying the role of a revolutionary healer, puts in full view the complexity of Black life in America. In the series he pairs his subjects with “found objects, evoking personal memories, ancestral connections, and the collective American past.” History, memory, and humanity meet.

In the painting Our Folks, you see only the young man’s face, no body. It is vintage. It is a story of a time long past but still remembered. His face, resolute, elegant, strong. In his eyes, you can almost see the pain; you feel the piercing gaze as if there is something to be uttered but never mentioned. Around his neck are American flags, a sort of emblem. Worn like jewelry one has not asked for. They are everywhere. Worn, but not choking him. The sites of memory or a memorial of people like him who have long been forgotten. But also, worn as a sign of love. His face, still resolute.

He has Langston Hughes’s dark face, dark eyes. He looks at you. Stares, even. You look back. There is intimacy, connection even. I know that look. I have felt that from time to time. The look of anger, wanting to tell of what has happened, but what others see is the country, its goodness, its shiny medallions around one’s neck. What story does this young man’s eyes tell? There is no grin. Or is there? I look again. This time. I see more than rage. I see more than resistance. I see more. I see him. I see him in all of his dignity. I see myself. I see us. I see our endurance. We both know what we have gone through in this country. But we also know who we are. We know that there is joy. Yes there is struggle. But there is joy. We both know that there is more to us than what this country has done to us. So he looks back at me; he smiles. I smile too. No, our smiles will not protect us. But we are alive. Life is wide open to possibility. That is hope.

No, our smiles will not protect us. But we are alive.

The final word on Black life is not brutality but brilliance, beauty. We see the world; our eyes are no longer blind. We look at our bodies, our hands, and create the world that’s in our mind. A world where Blackness is boundless. Love is supreme. For us, it is not only resistance—it is resurrection. The final word? Alright. Do you hear? Do you feel me?