My college debating group often reserves rooms under false names. We’ve long been banned from using common rooms, so our secretary-treasurer would instead book a room for, perhaps, “United Students for the Stuart Restoration.” Eventually, we’d be caught debating and drinking, rather than merely singing Jacobite songs, and we’d relinquish the front as it, too, wound up on the ban list.

Everyone enjoys inventing the front groups and the frisson of slipping something by the stodgy administration. Still, I felt something was wrong when I heard the undergraduates of my college debate group making plans for the fall semester and talking, with excitement, of approaching it as a semester of secrecy in the catacombs. It took me a good way into a phone call with one of them to figure out why. Coronavirus might be a divine chastisement (or simply part of the post-Edenic enmities in the natural world), but it isn’t a persecution.

It’s a tempting image, and there is a degree of truth to it. We know that the gates of hell will not prevail against Christ’s church, and thus neither persecution nor pestilence has a chance of conquering. The story of the early church is a powerful reminder of what Christ promised: “For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in the midst of them” (Matthew 18:20). And the perseverance of persecuted Christians is a continuing testament to this commitment.

In a persecution, we take pride in being as “wise as serpents” as we evade our pursuers. But evading the rules our school is setting this year would have been neither courageous nor prudent. Instead, my debate friends adapted to the real constraints that they, my family, and my church have spent the year chafing under. We have had to pull back from many of our habits and traditions, and, although a vaccine is on the horizon, it will be well into the year before enough people are inoculated to stop the spread.

We’re still in a period of waiting, but, if catacombs aren’t quite the right image, neither is hibernation—we still have important work to do.

What I keep coming back to is the image of a generation ship.

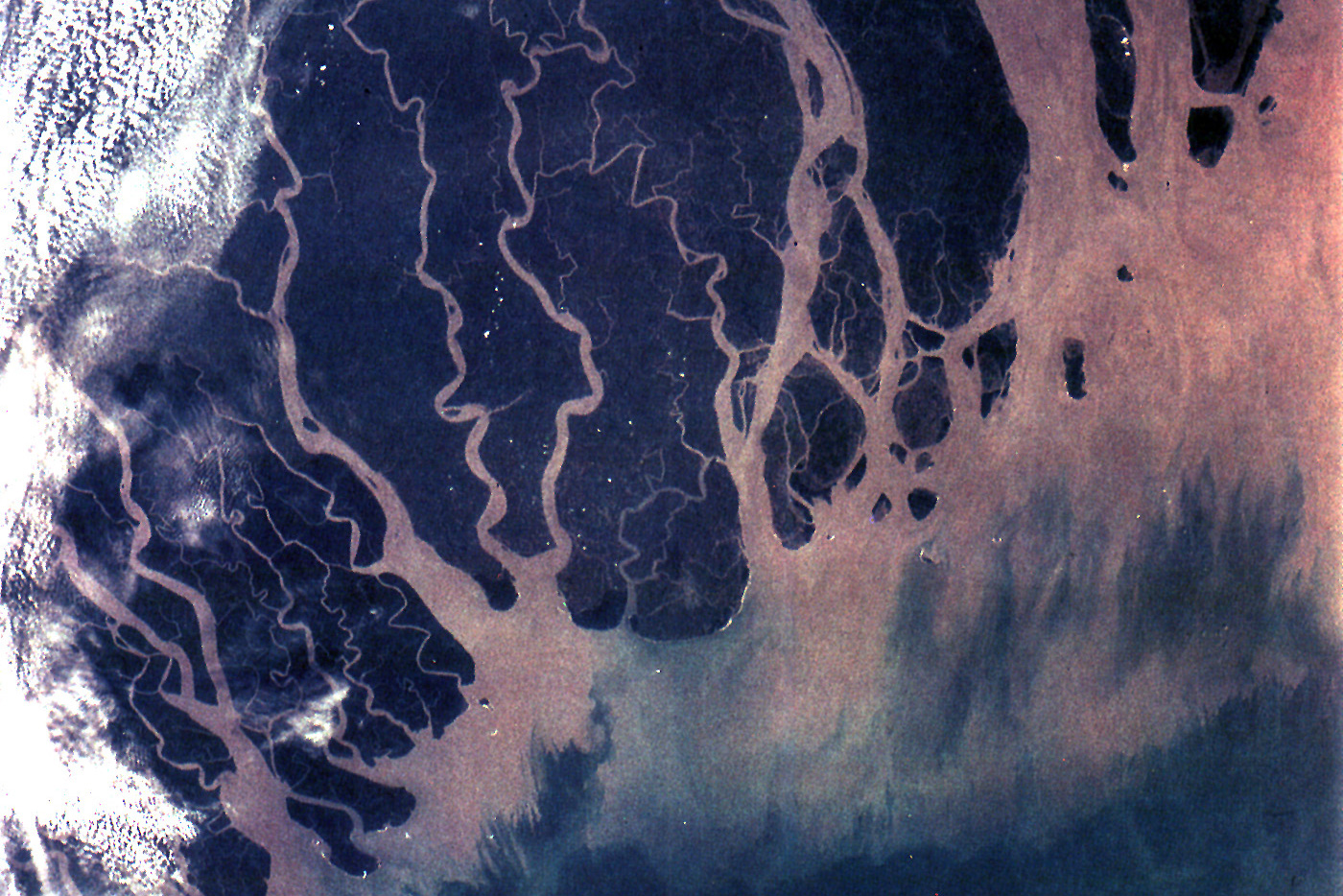

Some science fiction is built around faster-than-light travel and communication—stories where the vast distances of space are domesticated. Generation ships belong to a different kind of story, where even as humans voyage outside of our solar system, we are still very small people in a very big world. There is, in these stories, no FTL travel. There are no shortcuts.

Delivering on the promises of a generation ship requires committing to specific practices of stewardship. And whether you’re safeguarding a ship or a community, the core practices remain the same.

A generation ship spans the wide gap of time between planets. No one aboard at the beginning of the journey expects to see the destination. They commit to the ship in order that their children, or their children’s children’s children will see and reach the promised end.

Delivering on the promises of a generation ship requires committing to specific practices of stewardship. And whether you’re safeguarding a ship or a community, the core practices remain the same.

Cross Train on Different Skills

Redundancy is the watchword of a generation ship. Nothing can have a single point of failure—and only two layers of redundancy is perilous. If the single oxygenator fails, you won’t be able to make repairs before you suffocate. During normal times, you might have been able to focus on what you were best at or what you liked best (and if you were lucky, they overlapped).

But now the best person isn’t available or may not be available when we need them. It’s up to us to cook, to garden, to help the elderly neighbor whose son can’t fly in to visit.

It’s a somewhat humiliating time, as we fumble through tasks for which we used to rely on others. It’s a time of learning the value of whatever kind of work we usually avoid and delegate, and carrying our new understanding of the weight of that work into the new world we anticipate.

Expect Deterioration

From the moment a generation ship sets off until well after it arrives, things keep getting worse. The whole journey is conducted in the absence of places to reliably resupply—you’re usually limited to what you started with. A generation ship isn’t intended for multiple trips; it just has to stay ahead of entropy long enough for its people to be settled in their new home.

Between now and whenever it feels fair to say things are normal again, it will be normal to be exhausted or dispirited. Many of the ways we take care of each other and ourselves are limited, and the last thing needed on top of the stress of deprivation is the pressure to make our lives resemble “normal” in the middle of a long-lasting disaster.

Parents working from home with their children don’t do the same kind of work they did in an office. Virtual prayer circles lack some of the serendipitous moments of intimacy that come outside the normal programming. You can move the official part of the gathering to Zoom, but not the ride home one attendee offers another to avoid the rain. And no organizer can plan for the long, unpleasant evening clearing a backed-up toilet that becomes the foundation of a friendship.

Your best in these circumstances won’t look like your best before. And you’re not being asked for what belonged to another time. You just need to do enough to make it through to the time of rebuilding.

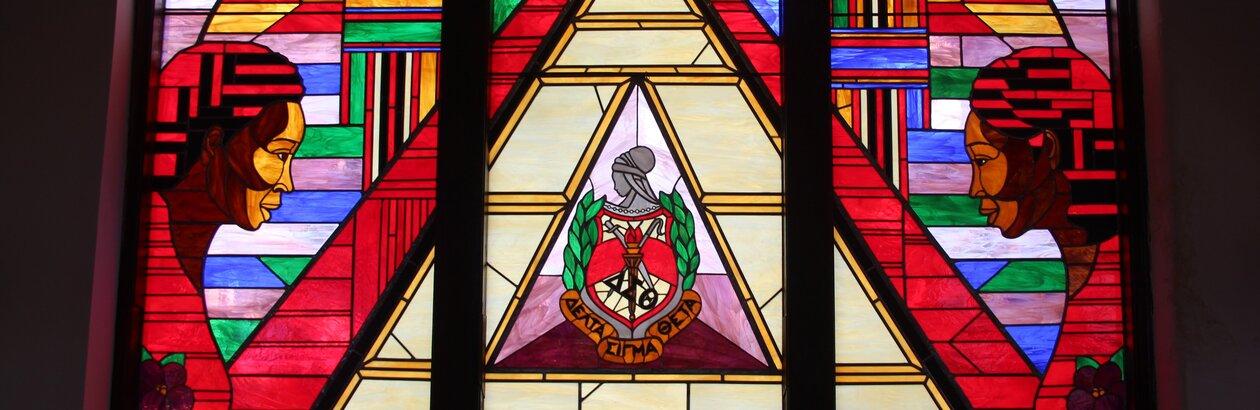

Weave Essential Knowledge into All Parts of Life

In generation ship stories, the children of the ship play with models of the engines. Algal food protocols are conserved through nursery songs. The walls are painted with murals of the history of the ship and the future it was built for. All these things are too important to be left only to classroom instruction.

The same is true in our own lives. Whatever is most important should be before our eyes and knit into our bones. If you can’t see the people you love, hang up their pictures in your house, and schedule a monthly phone call. If it isn’t safe to gather for worship, make your home a place of contemplation, hanging up religious art. You may already begin meals with thanksgiving, but where else should your daily routine include an invitation to be with God?

Look over your usual days and ask, What instruction have I laid out for myself? Do I want to become the person I’m implicitly teaching myself to be? Revise accordingly.

Plan for an Unknown World

Generation ships are usually aimed at a destination that no one has ever visited before. Their holds are packed with seeds, shelters, sacred things—whatever they think they will need to start over from scratch. In some stories, they even carry biotechnology so they can remake themselves to fit their new world, rather than terraforming the world to suit them.

We must aim to do better than return to the old normal. During our journey, as everything is upended, we want to try to root out systemic injustices that were woven into our schools, our zoning laws, our carceral system. What we loaded on at the beginning of our journey isn’t what we want to plant on a new world.

Jobs have been forced to acknowledge the existence and needs of children in a way they had deftly avoided during the pre-pandemic times. When it’s safe to return to work, we shouldn’t expect or allow employers to operate with the same inflexibility they had in the beforetimes.

We aim to conserve the best of our old lives and to discover new strengths and new traditions as we go. A generation-ship mentality embraces the continuing crucible as an invitation to become more deeply rooted in what matters most, to leave behind whatever evils we’ve allowed to accumulate, and to discover new gifts. We can’t narrow our vision to only work toward what will be won in one lifetime.